Preface

Vine Deloria Jr., like all human beings, was a man of complications and contradictions. Unlike most, his complexities were sometimes lived out under public scrutiny. Nowhere was this more the case than in his understanding of faith, tradition, and spiritual practice. Some have wondered how he squared his work in politics and lawwhich required a national vision and a profound secularismwith his equally vehement insistence on the power and validity of indigenous (and, indeed, all) spiritual experience. Given this insistence, they ask, why was he not a more active participant in the spiritual life of Indian people? These are not unfair questions, and the book you hold in your hands offers at least some sense of his understanding.

Tracing Vine Deloria Jr.s career, one might follow a trajectory that runs from his initial engagement with Indian policy and politics as executive director of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), to the literary and legal activism that followed the 1969 publication of Custer Died for Your Sins , to later engagements with theology, philosophy, and metaphysics, to the critique of the politics of scientific knowledge that characterized his last years. Such a periodizationentirely reasonable, by the waywould, however, separate out long-lasting and overlapping interests. His career was as much a layering of these things as it was a progression from one to another. It would also ignore a curious and vital part of his lifean intellectual bedrock that developed in relation to western philosophy and theology.

Vine Deloria Jr. graduated from Iowa State University in 1958. At the time, Iowa State was a college rather than a university, and it offered only the bachelor of science degree. He majored in general science, which meant a broad background in social and natural sciences. His formative intellectual experiences, however, came out of encounters with the theological and philosophical classics. Wishing to pursue these fields further, he entered the Lutheran School of Theology in February 1959, graduating, after a couple of detours, in 1963. He had, in other words, a long and sustained interest in questions of spirituality, faith, knowledge, and practice. Though that interest would later prove well suited to bridging indigenous and Western traditions, the possibility of such bridging was latent and undeveloped in the mid-1960s.

His experiences at NCAI and the publication of Custer Died for Your Sins changed everything. Vine Deloria Jr. rapidly developed his political and rhetorical talents in a national arena, which required an orientation to big pictures and strategic contexts. He cultivated what would become an unparalleled expertise in the legal and political situations of hundreds of tribes across the country. He trained himself in history, law, politics, and education, and he learned the ways of the American academy. All of these things he did to advance the place of Indian people in the world. In celebrating this overriding, unwavering purpose, it is critical to understand that his seemingly secular actions originated in a spiritual history, one that, as he has recounted in the book Singing for a Spirit , stemmed from a four-generation family vision of broad, cross-cultural leadership. His political and intellectual pathwhich had both spiritual origins and spiritual consequences pointed him away from a specific, intimate engagement with any home community. And if there was one essential of which he was convinced, it was that indigenous spiritual practice relied decisively upon the unity and presence of a human-scale community. He found himself arguing for the power and legitimacy of indigenous spirituality then, without engaging substantially in its practice. This disengagement had no small measure of irony, perhaps, but it should also be read as a measure of his understanding of and respect for that practice.

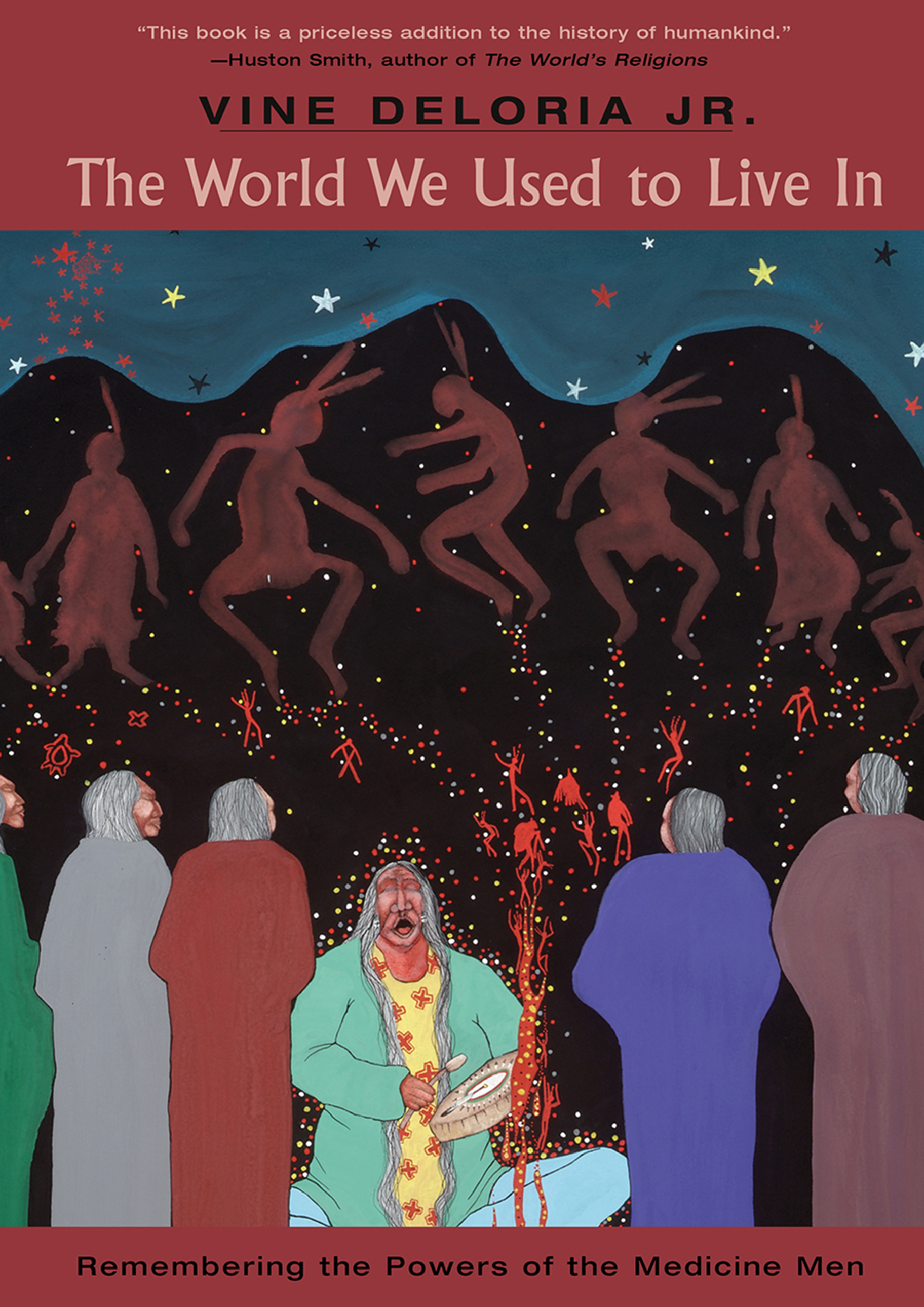

Vine Deloria Jr. passed to the spirit world on November 13, 2005. Only days before, he finished the final revisions of this manuscript. An apparently simple and straightforward book, it can also be seen as a complex kind of coming home, a weaving together of the many strands of his life and work. At the broadest level, this project returned him to his oldest interests in theology and experience and led him to decry the gross secularism that has devalued all spiritual tradition. Writing as a historian, he insists that old accounts of spiritual power be read not in terms of magical trickery or performance, but as real manifestations of the permeating reality of indigenous spiritual power. He speaks, as always, directly to Indian people, calling forth what has been lost and raising the possibility that contemporary ceremonies are simply walk-throughs that have little effect on participants. Given the importance of ceremonial life to Native people today, the critique has the potential to be a devastating one. Optimistic to the core, howeverand in the spirit of the critiques he willingly launched at tribal politics, leadership, and educationVine Deloria Jr. did not fail to offer an indigenous alternative.

Not surprisingly, he uses logic to make an argument about faith. Reshuffle the categories that have been used to sort hundreds and hundreds of reports of indigenous spiritual power, he tells us, and you will find that what has been easily read as anomalous should, in fact, be taken as representative of a different and better world. Real power, in other words, exists in and on this earth. That argument is then linked to his critique in order to provide a road map for the future. If we can but see the possibilities that our ancestors experienced, he argues, we can recapture the reality of spiritual power for Indian people today. His own words, as usual, express his desire better than any others: A collection of these stories, placed in a philosophical framework, might demonstrate to the present and coming generations the sense of humility, the reliance on the spirits, and the immense powers that characterized our people in the old days. It might also inspire people to treat their ceremonies with more respect and to seek out the great powers that are always available to people who look first to the spirits and then to their own resources.

The legacy of Vine Deloria Jr. is rich and complex, bridging multiple kinds of knowledge, multiple sets of people, and multiple visions of the future. This book offers a fitting capstone to his career, for it encapsulates those multiplicities, while also returning to the root, the core, the bedrockhis own faith in the powers that exist in the world and in the ability of Indian people to draw upon them as resources for Indian futures. It is, in many ways, the work of an elder, a label my father resisted for a very long time. This fall, as he struggled with his health, it came to seem, to me at least, that he passed into a new kind of intellectual experience. He had perceived the virtues of an elders wisdoma deep, reflective, and meditative sensibilityand he had embraced those virtues. This book, which is so much about listening to the old ways, marks not simply his passing, but a loss that we have only glimpsed. The world has known Vine Deloria Jr. in the spring, summer, and autumn of his life. We can only imagine the things he would have been able to say as an elder, during a wintertime of reflection. This book stands, then, as a taste of that which we will never know.

Philip J. Deloria

Prologue

Traditional Religion Today

Sweat lodges conducted for $50, peyote meetings for $1,500, medicine drums for $300, weekend workshops and vision quests for $500, two do-it-yourself practitioners smothered in their own sweat lodgethe interest in American Indian spirituality only seems to grow and manifests itself in increasingly bizarre behaviorby both Indians and non-Indians. Manifestos have been issued, lists of people no longer welcome on the reservations have been compiled, and biographies of proven fraudulent medicine men have been publicized. Yet nothing seems to stem the tide of abuse and misuse of Indian ceremonies. Indeed, some sweat lodges in the suburbs at times seem like the opening move in a scenario of seduction of naive but beautiful women who are encouraged to play the role of Mother Earth in bogus ceremonies.

![Deloria Jr. - Behind the trail of broken treaties an Indian declaration of independence. [The goundbreaking work by the preeminent spokesperson for American Indian rights]](/uploads/posts/book/171989/thumbs/deloria-jr-behind-the-trail-of-broken-treaties.jpg)