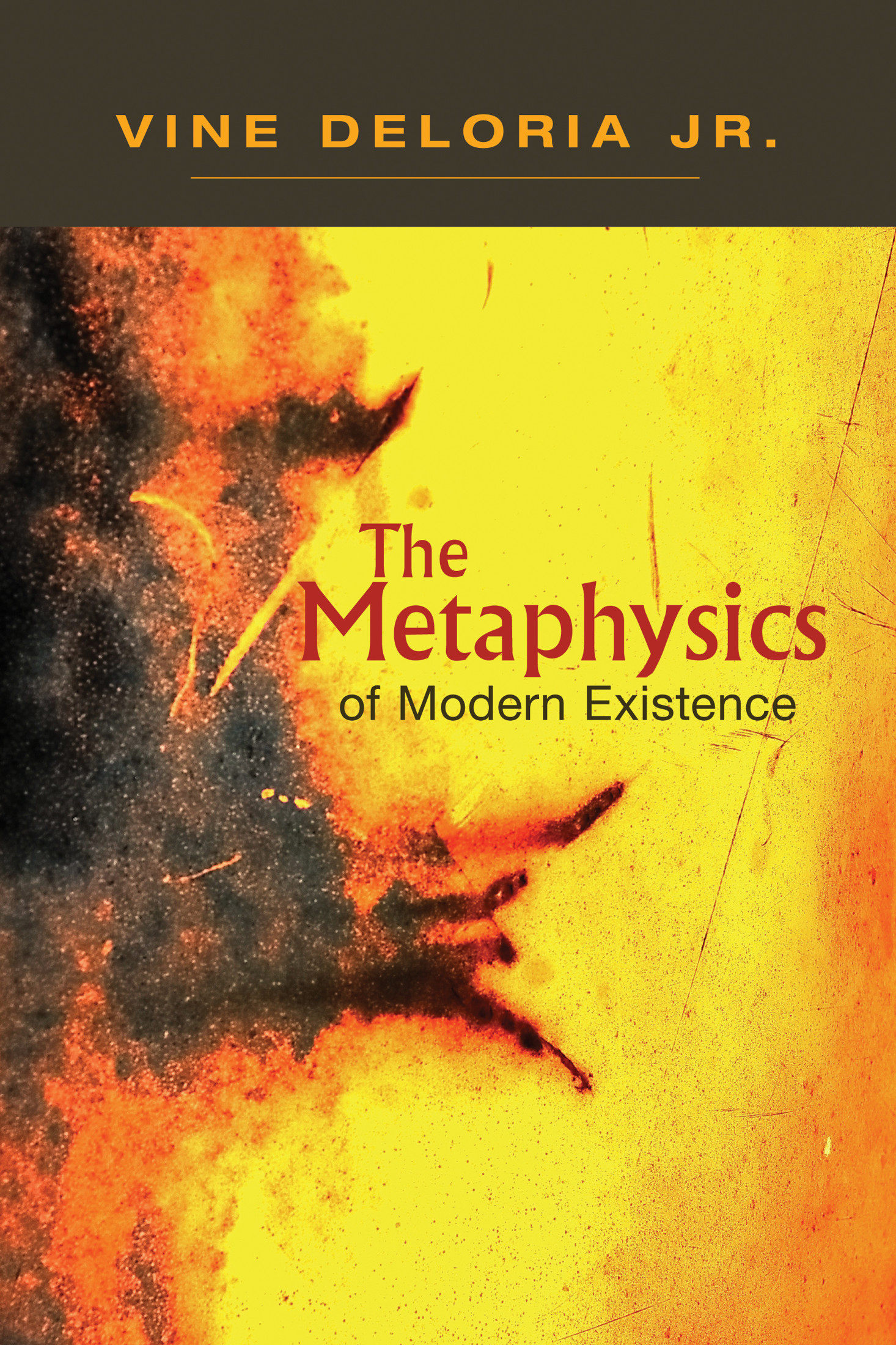

Vine Deloria Jr.

Foreword by daniel r. Wildcat

Afterword by david E. Wilkins

1979, 2012 Vine Deloria Jr.

First published by Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1979

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval systemexcept by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a reviewwithout permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Deloria, Vine.

The metaphysics of modern existence / Vine Deloria, Jr. ; foreword by Daniel R. Wildcat ; afterword by David E. Wilkins.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

ISBN 978-1-55591-759-3 (pbk.)

1. Religions (Proposed, universal, etc.) 2. Religion and culture. 3. Indians of North America--Religion. 4. Civilization, Modern--Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title.

BL390.D43 2012

191.08997--dc23

2012019923

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Design by Jack Lenzo

Fulcrum Publishing

4690 Table Mountain Dr., Ste. 100

Golden, CO 80403

800-992-2908 303-277-1623

www.fulcrumbooks.com

One

A Planet in Transition

Throughout most of human history, people have lived as tribal groups in small villages in relatively isolated areas. They have been born, have married, given birth, grown old, and died unaffected by events, beliefs, and developments of other groups of human beings on other parts of the planet. Even the great empires of ancient timesChinese, Assyrian, Egyptian, Persian, and Romanhailed as magnificent and world encompassing in their heyday, did not affect a significant number of human societies, and they enjoyed decades of prosperity without exploiting more than a tiny percentage of earths natural wealth. There was no concept of world history aside from the local interpretations of small nation-empires, which saw in their origin and rise to prominence a paradigm for understanding the meaning of human existence. But each in turn suffered a decline and collapse, leaving little more than exotic pottery and massive ruins.

A radical transformation of all human societies occurred when the European explorers discovered the Western Hemisphere. Suddenly the scope of planetary existence began to take shape, and the people of Western Europe spread over the globe exploring, colonizing, and finally exploiting the lands and peoples that had formerly lived in relative isolation. European languages replaced tribal languages in many lands, and first French and then English became the tongue of the civilized world, of diplomacy and trade, and finally of the accepted expressions of civilized values. Through the establishment of colonial administrations, Western European political forms were thrust upon non-Western peoples, and Western economic interests came to dominate the economies of other continents. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Earth was conceived as a gigantic garden designed exclusively for the benefit and entertainment of Europeans. Other peoples existed as much for the sake of European tourist visitations as for themselves, and the quaint and exotic seemed to be the only acceptable characterizations of non-Western societies.

Because the business of Western Europeans was business, their technology and industrial capabilities became the dominating influences in social and political change throughout the world. Their standard of living became the goal toward which the other peoples of the globe aspired, and their forms of entertainment and relaxation became universally accepted as expressions of luxury. European political ideas were thrust upon non-Western nations in varying degrees, and while democracy was extolled as the ultimate human virtue, European nations were reluctant to grant any measure of self-government, even in a democratic sense, to the colonized nations they controlled. In those areas where the European nations became weak and lost colonies, particularly in South America, the former colonies instituted their own brand of European economic and political forms, which were as oppressive and dominating as any European institutions.

The Second World War brought an end to the period of colonization. It was the first truly planetary struggle, and although it began as a quarrel among European neighbors over the expansion of German living room, it soon embroiled the colonies and trust lands controlled by European nations. The alliance between Germany and Italy, when expanded to an Axis coalition to include Japan, ensured that the struggle would be waged from pole to pole and in all continents. Calling on their colonial peoples to resist Axis domination, the Allied forces justified their military expeditions and atrocities on their alleged support of four basic human freedoms, which Axis totalitarian theories seemed to deny. And with the assistance of colonial armies, the Allied forces were victorious, forcing the total collapse of the Axis powers and their surrender.

Following the war, the victorious Allied powers attempted to rejuvenate their faltering colonial empires, but with little success. The cry for freedom that had inspired diverse peoples to resist the German and Japanese armies now inspired them to seek political and economic freedom from their colonial masters. For many smaller nations, the Second World War was not a struggle to keep from learning German or Japanese but the beginning of a long and bitter effort to free their lands from all foreign domination. In some instances the European nations saw little to be gained by continued colonization of remote lands. Pretending that independence was a reward for faithful services rendered during the war, they granted a form of freedom that ensured strong economic ties but allowed a measure of political independence.

Not all nations received such a gratuity, however, and particularly in Southeast Asia and Africa, the European nations made every effort to retain their colonial possessions. Thus France, Belgium, and Portugal struggled with wars of liberation conducted by patriots in their colonies in the decades following the war, and these powers surrendered their claims only when the war became so costly as to threaten the collapse of the mother countrys economy. The decolonization process is hardly concluded, but at present it seems inevitable that European political control over all lands will be eliminated, except in those where European immigrants have totally settled, such as New Zealand and Australia.

In three decades of decolonization, eighty new nations were established from the ruins of old colonial empires. For the most part, this was a peaceful process in which the European nation assisted in founding a democratic form of government often modeled on its own. Today, only eleven of those democracies survive; the rest have fallen victim to revolutions and political coups, often choosing some form of dictatorship that guaranteed social and economic stability over the chaos of a democracy in which the basic economic foundations were still controlled by foreign interests. Seven of the eleven are today little more than island republics, isolated for the most part from important developments in world affairs and content in their limited relationships with larger powers. This transitional process from democracy to totalitarian governments has been interpreted by Western leaders as an indication of the decline of Western humanistic traditions, and some American political leaders have privately admitted that their goal for foreign policy is to secure a guaranteed second-best status for Western nations in a world increasingly hostile to the Western way of life.