Copyright 2018 Hugh A. Dempsey

Illustrations copyright 2018 Alyssa Koski

Foreword copyright 2018 Pauline Gladstone Dempsey

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, audio recording, or otherwisewithout the written permission of the publisher or a licence from Access Copyright, Toronto, Canada.

Heritage House Publishing Company Ltd.

heritagehouse.ca

CATALOGUING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

FROM LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

978-1-77203-217-8 (pbk)

978-1-77203-218-5 (epub)

Edited by Lenore Hietkamp

Proofread by Lesley Cameron

Cover design by Jacqui Thomas

Interior design by Colin Parks

Cover and interior illustrations by Alyssa Koski

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

CONTENTS

PUBLISHERS NOTE

This collection of stories about Napi the trickster contains graphic violence, including scenes of rape and murder. The author explains that when these stories were recorded at the turn of the twentieth century, the Blackfoot people told them to audiences of all ages, but today the stories are more suitable for adults than children.

FOREWORD

I was introduced to Hugh Dempsey by my father, James Gladstone, at an Indian Association of Alberta meeting on February 5, 1950. My father was the president of the IAA at that time and Hugh was the provincial editor of the Edmonton Bulletin. For the Native peoples of Canada, the IAA was seeking such rights as family allowance, old age security, and hunting.

Hugh, at twenty-one, was reported to be the youngest editor on a daily newspaper in Canada. That is when he began a lifetime of devotion and dedication to the Indian people. Thinking back, it was the beginning of both his and my fathers careers, which blossomed throughout their lives, demonstrating a dedication that persists for Hugh to this day.

Sometimes I pinch myself when I think of the wonderful people who were in the twilight of their years in the 1950s. There were men and women such at Bobtail Chief, Suzette Eagle Ribs, Sinew Feet, John Cotton, Jack Low Horn, Jim White Bull, Vickie McHugh, Jack Black Horse, One Gun, Chief Shot Both Sides, and the list goes on and on. While Dad listened to them speaking of their rights, Hugh spoke to them about their experiences and their stories of bygone days. Some had actually been at the last battles held around Fort Whoop-Up.

At a young age, I noticed Hughs mind was like a sponge. Not only were people willing to share their knowledge with him, but they were fascinated that someone was interested in hearing their stories and reminiscing with them.

Hugh wrote about the knowledge that was passed on to him. First were the stories relating to the history of the Blackfoot tribes, and then the stories about culture and religion. I have been told that the information he gathered back then was of such value that the young people of today are using it, as will future generations. He hopes his work will inspire young Native people not only to learn of the colourful backgrounds of their ancestors but also to become writers themselves.

Hugh records a history that otherwise would have died with the Blood, Peigan, and Blackfoot elders. I am so grateful that I was there when all this was unfolding. And for being asked to voice my humble opinion.

Pauline Gladstone Dempsey, Calgary, Alberta

Daughter of Senator James Gladstone

Member of the Blood Tribe, Blackfoot First Nation

Recipient of the Chief David Crowchild Memorial Award (1987) and Alberta Achievement Award (1988)

INTRODUCTION

When I first went among the Blackfoot sixty-four years ago, I was impressed by the richness of their history and culture. And when I married into the Blood tribe, lifelong friendships were established with people like Gerald Tailfeathers and Everett Soop. Then, through my father-in-law, James Gladstone, I met the elders who were the repositories of tribal lore, and I found them more than happy to share their knowledge with me. At first I concentrated on the history of the three tribesthe Bloods, the Blackfoot, and the Peigansand the elders provided graphic images of what life was like in the buffalo days. My research carried me forward to contemporary issues and then backward to mythical figures such as Napi, the Old Man of the Blackfoot.

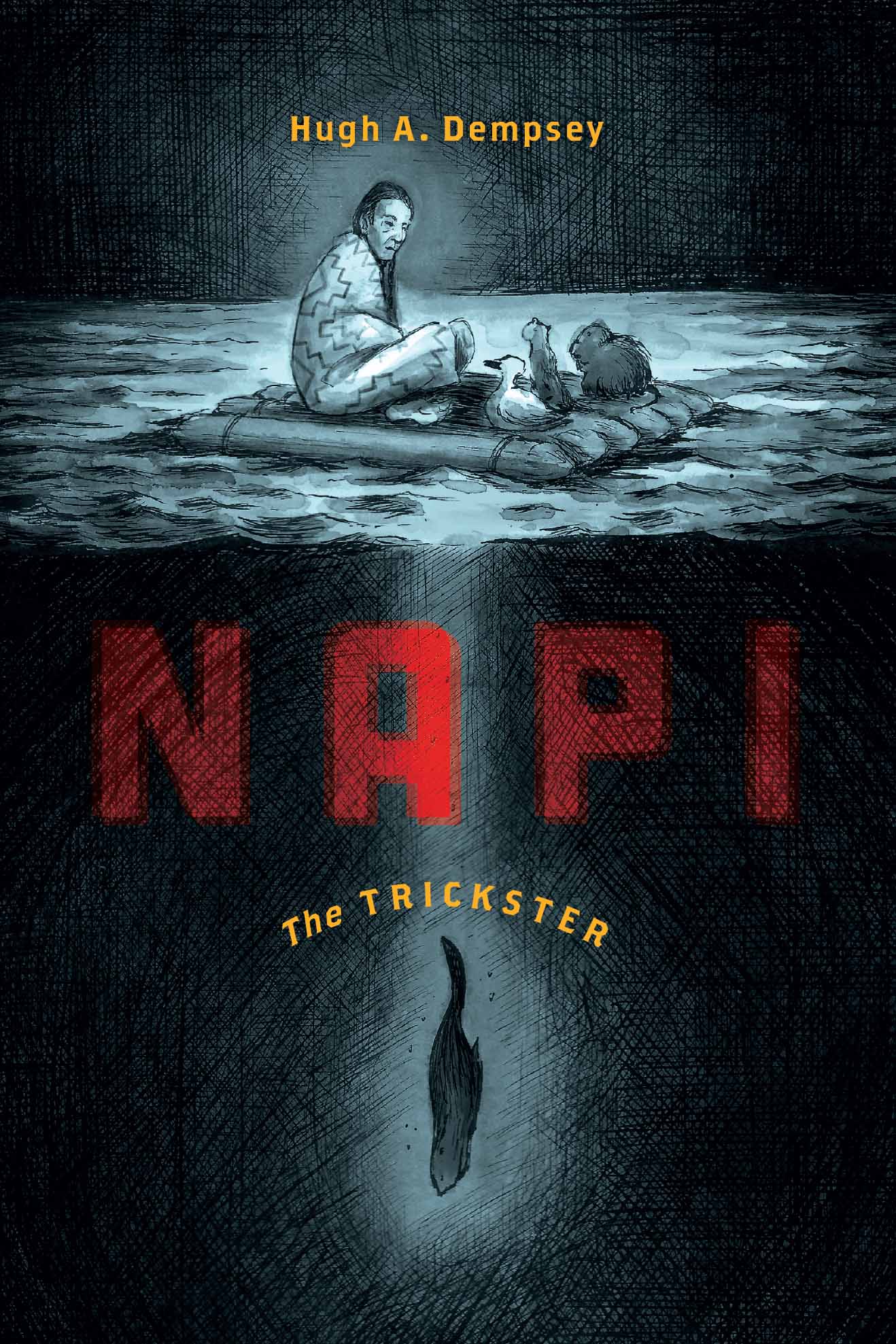

Napi is a creature of legend, a figure that appears prominently in mythology, sometimes as a quasi-creator, sometimes a fool, and sometimes a brutal murderer. He was generally considered to appear in the image of man. He personified strength through his supernatural powers, but his power was not reined in by reason. He was a trickster, deceiving everyone he came into contact with, frustrating them, confusing them, and even killing them. I learned that Napi was credited with creating the earth and everything on it, but he was not a hero figure. Rather, he possessed all the weaknesses and strengths of man but in a supernatural way.

Over the years I have heard many Napi stories, sometimes in the style of the old people, and at other times heavily laced with aspects of Christianity. In some of the modernized stories, there was even confusion between Napi and Santa Claus. The stories told here are ones that were told at the turn of the twentieth century, when they were less affected by influences of the modern world. No stories were omitted because of modern sensitivities. Rather, virtually the whole body of Napi stories is included: tales of wisdom, foolishness, sex, greed, pity, murder, and generosity. They are rife with adventure, serving as object lessons for the young or as amusement during dark evenings in camp.

NAPI IN BLACKFOOT CULTURE

Although Napi is said to have created many of the objects and creatures on earth, and even earth itself, he was never considered to be god-like. If anyone asked a Blackfoot if they ever prayed to Napi, the question would be greeted with hilarity. Napi was superhuman and could do miraculous things, but he was never revered. How could they feel devotion for someone who killed babies, disfigured animals, and roasted prairie dogs alive? How could they respect someone who was unbelievably foolish and naive? Anthropologists have called him a trickster/creator, which is probably as good an expression as any. He was man personified, for in almost any Napi story one can see a real counterpart in human form.

The Napi stories, according to the ethnologist Clark Wissler and his local interpreter and assistant David Duvall, recite the absurd, humorous, obscene, and brutal incidents in the Old Mans career. The authors say that the stories are not the basis for any ritualistic or ceremonial use, as with the star myths, but they do contain a significant amount of detail on Blackfoot material culture from an early period. There are references to stone knives, mauls, digging sticks, scalps, baby swings, and buffalo jumps as well as accounts of making weapons, dressing skins, and cooking.

People who hear Napi stories are seldom sympathetic to the situations he has created for himself, nor do they always understand his motives. Rather, the more outrageous and foolhardy Napis actions, the more a Blackfoot audience would laugh. No matter how desperate his situation, they knew he would escape.