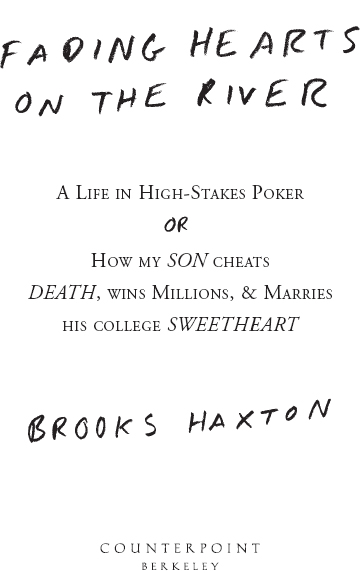

FADING HEARTS ON THE RIVER

Copyright 2014 Brooks Haxton

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Haxton, Bruce.

Fading hearts on the river: a life in high-stakes poker / Bruce Haxton.

pages cm

1. Poker. I. Title.

GV1251.H28 2014

795.412--dc23

2013044915

ISBN 978-1-61902-375-8

Cover design by Matt Dorfman

Interior Design by Megan Jones Design

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my family, heart-winners each and all

Lucky and unlucky mean the same thing, like flammable and inflammable.

WILLIAM MATTHEWS

To fade hearts on the river, in Texas hold em,

is to avoid a heart on the final card,

so that the other player does not complete a flush in hearts

to win the hand.

CONTENTS

where

ISAAC & ZOE

at the prospect of BIG CASH

CONTEND

with RISK and PLEASURE

in the GAME

U NDER THE FLOODLIGHTS on the veranda of the Atlantis Casino the chip leader leaned over the table, his face hidden behind dark glasses and shoulder-length brown hair. By the time I watched him on the video, I knew what was about to happen, because he was my son, Isaac, and this had been the start of his career in tournament play. But to see him in action, counting out chips and sliding a raise of more than $40,000 into the pot, felt unreal.

He still looked to me like one of the boys in a high-school grunge band. But the bloggers were calling him the Lizard King. At his age I would have killed to be taken for Jim Morrison, but I looked nothing like him. If you brush the hair back from his face and take off the dark glasses, Isaac looks like me: sensitive with his guard up, brainy and ironic.

His opponent, Ryan Daut, looked clean-cut, sad and pensive, almost monastic, sitting still with his head tilted to one side, hands folded, while he studied Isaacs body language. The raise was a problem in his mind. Ryan had come here on his break from the Ph.D. program in mathematics at Penn State. Isaac was taking time off after three years in computer science at Brown. The odds against either player making it this far into the tournament had been about five hundred to one.

Like them, I had planned for a time to teach college math, but I too took a chance instead. I spent hours every day writing poetry. I could see the odds: a tiny percentage of those who try to write memorable poems. Meanwhile, I wanted to support myself as a teacher of writing, and this was a long shot too. Playing against the odds in poetry has developed ways of thinking different from what poker requires of my son. Still, I want to understand him.

On the floodlit veranda the odds seemed to be turning in Isaacs favor, though the wind kept driving storm clouds over the lagoon and riffling the edges of hundred-dollar bills in bundles on the felt. A few summers earlier, both Ryan and Isaac had worked temporary jobs and spent their weekends with the other gaming geeks from their respective high schools, calculating strategy in StarCraft and Magic: The Gathering. Isaac and one of his closest friends were competitive against the best Magic players in the country.

When Ryan and his StarCraft friends took measurements one night, he once told an online interviewer, he took the honors, and that was why in his favorite poker forum, people knew him as BigBalls. In Isaacs favorite poker forum, people knew him as Ike, but his usual screen name at the tables was F33DMYB0NG, the logic behind which was to sound like such a brainless stoner that people would underestimate the intelligence of his play and make mistakes, which helped him, paradoxically, to feed his bong. More importantly, to my way of thinking, his opponents errors had been paying his tuition.

Dozens of math nerds all over the world had taken silly screen names and started winning more per hour than most doctors and lawyers make. For each of these regular winners online, at any given time, by Ryans estimate there were four losers. The losers burned out fast, but newcomers were plentiful.

In tournament play, as I was saying, the odds were worse. Among the 935 players who entered this tournament, including some of the most skillful in the world, 6 out of 7 lost the entry fee, leaving the prize pool for the others at more than $7 million. First place alone was $1,535,255, far more than I had earned in my whole life as a teacher and a writer. But for Ryan and Isaac the play of numbers and the flow of the game had more reality than what the numbers were supposed to represent.

In the next six years of tournament play Ryan and Isaac would not meet again at the final table. They would see each other only a few times. After this tournament, Ryan would win less than he spent on entry fees. His worst-case scenario for this evening, however, was to win $861,000, more than a hundred times what he had paid to enter. Several weeks earlier, Isaac had paid $175 to play a satellite online. By finishing first in the satellite, he had won a seat here in the main event, together with a trip to the Bahamas, all expenses paid. Now the smallest return Isaac could expect on his $175 was 500,000 percent.

With both players guaranteed to win so much, it might have been healthier to consider the money and the odds at this point inconceivable. What rattled me, as usual, was trying to make sense of things. The sum they would be divvying up in the next few hands was not quite $2.4 million. But it was slightly more than $2.397 million, $44 more. In my home game no one has ever won as much as $44.

Had I been there on the veranda with Isaacs girlfriend Zoe, where my wife Francie and our thirteen-year-old twin daughters were, just off the plane, it would have been unbearable for me to follow what came next. I would have been a wreck all day. It was difficult enough to think about it at a distance.

Isaac and Zoe told me later that he felt exhilarated when he went to meet the other players for the final table. Before she left the room that morning, Zoe had chosen an outfit, dressed, taken one last look, and started over. Later, on camera, she looked beautiful. But she was as anxious as I would have been. Every time she stood up at the rail, her head was swimming with huge sums of money risked on the fall of a single card. Her knees lost strength. They trembled. They were giving out. She understood the game, but she was too worked up to follow what was happening. Francie and our daughters Miriam and Lillie could follow less. Isaacs friends kept having to tell them what was going on.

Next page