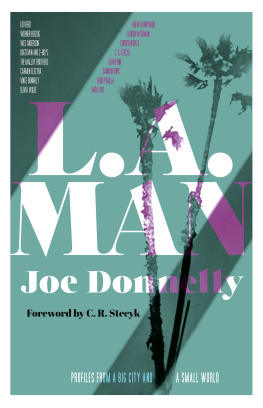

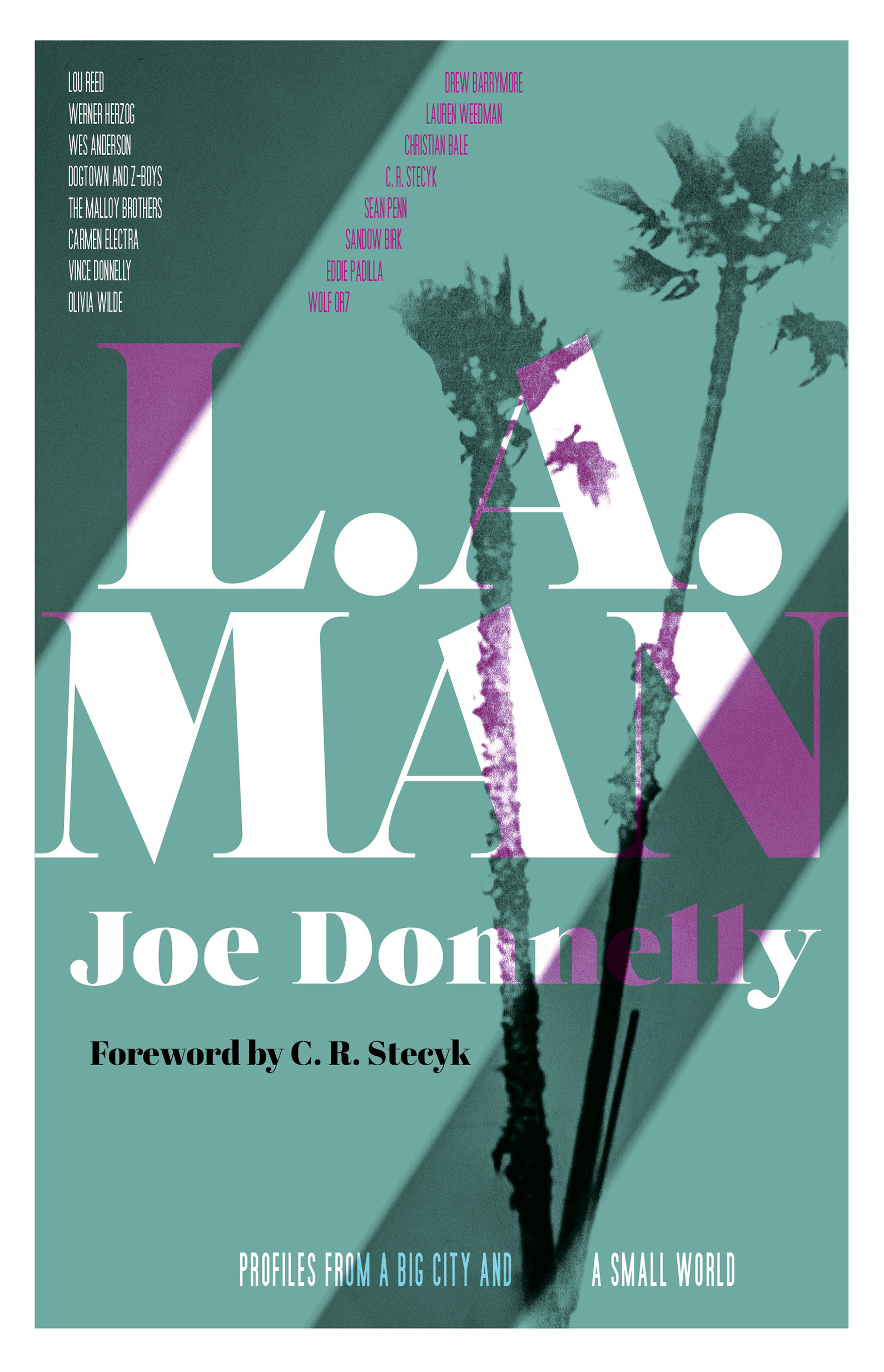

this is a genuine rare bird book

A Rare Bird Book | Rare Bird Books

453 South Spring Street, Suite 302

Los Angeles, CA 90013

rarebirdbooks.com

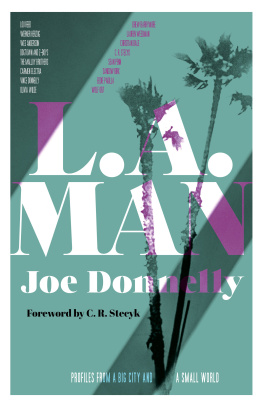

Copyright 2018 by Joe Donnelly

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever, including but not limited to print, audio, and electronic. For more information, address: A Rare Bird Book |

Rare Bird Books Subsidiary Rights Department,

453 South Spring Street, Suite 302,

Los Angeles, CA 90013.

Set in Minion Pro

epub isbn : 9781947856660

Publishers Cataloging-in-Publication data

Names: Donnelly, Joe James, author. | Stecyk, Craig, 1950-,

foreword author

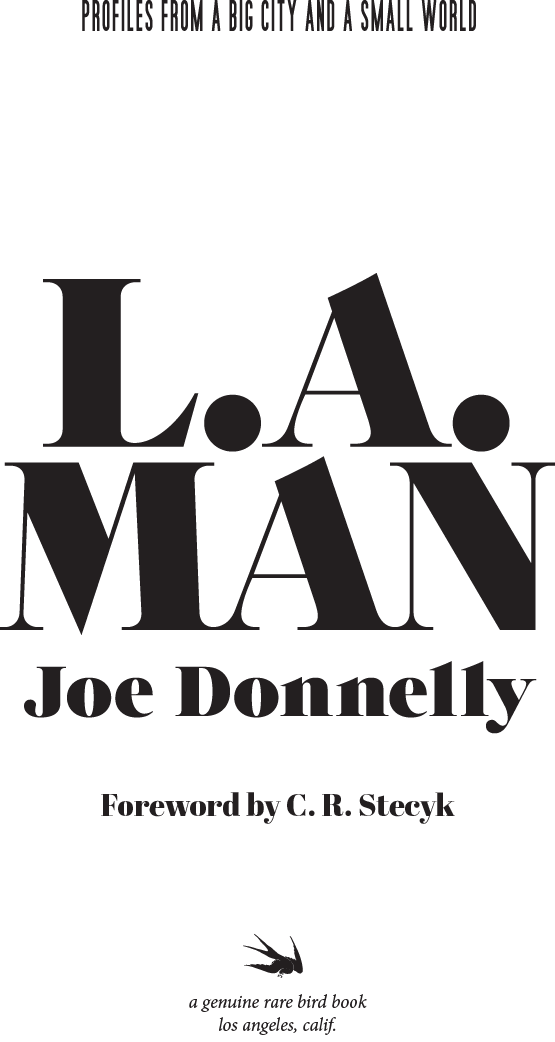

Title: L.A. man : profiles from a big city and a small world / Joe Donnelly ; foreword by C. R. Stecyk.

Description: First Trade Paperback Original Edition | A Genuine Rare Bird Book | Los Angeles, CA; New York, NY: Rare Bird Books, 2018.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781945572876

Subjects: LCSH Los Angeles (Calif.)Biography. | Hollywood (Los Angeles, Calif.)Biography. | Los Angeles (Calif.)Social life and customs. | CelebritiesHomes and hauntsCaliforniaLos Angeles. | Motion picture actors and actressesUnited StatesBiography. | Popular musicCaliforniLos Angeles. | Rock MusiciansUnited StateBiography.| BISAC BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Entertainment & Performing Arts | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY /

Cultural, Ethnic & Regional / General

Classification: LCC F869.L853 D66 2018 | DDC 979.4/94053092dc23

For Olivia

Contents

Foreword

A recent blunt force head trauma had rendered me incommunicado. My memory recall was nonexistent. The old cranial bell had become permanently rung when my skull hit the hardwood deck of an indigenous boat traversing a rigorously strict Islamic archipelago. No idea how Joe D. got my number as I then had none, but he came at me out of the void, popping up and requesting an interview about matters that had transpired decades ago. My answer was an emphatic no. The previously described perpetual mental haze prevented my willing participation in such an exercise. That wasnt much of a deterrence to Donnelly who seemed more interested in my participation than my willingness.

Somehow, eighteen years later, Donnelly is still around and still demanding answers. Through his perpetual interrogations and musings he has morphed from the aforementioned terrorist into a well-respected member of my ohana. (I realize that this could perhaps be interpreted as a classic case of Stockholm Syndrome.)

This book is a lot like that/him/then/there/now. Glad tidings from an unrelenting inquisitor. Great work oftentimes hurts as well as heals. In times like these a good read is all that really matters.

C. R. Stecyk

Minor edits have been made to some of these pieces.

Driving Wes Anderson

Originally published as The Road Wes Traveled

in the LA Weekly , January 27, 1999

Authors note: Rushmore debuted in New York and Los Angeles on the cold, December day that Wes Anderson and I road tripped to Texas. I was between gigs and doing some freelancing when the great Manohla Dargis, then film editor at LA Weekly , asked me if Id be interested in a cover story on Wes Anderson, one that required accompanying the young director on his journey home for the holidays. Dargis was playing a couple of hunches. One was that Anderson, already in a precarious position after the lackluster performance of his charming debut, Bottle Rocket, had made a transformational film with Rushmore . The other was that I, relatively new in town, was the right guy to ride shotgun with Anderson while his fate unfurled in real time.

T he driver is breaking the law again. Tearing like a tornado across the Mojave wastelands in a rented white Ford Explorer. Hands at ten and two. Chewing highway. Approaching his favorite speed: ninety mph. What would the honorable folks at Disneys Touchstone Pictures think?

Had they done a background check before anteing up for this buggy, theyd have known it would be like this. Wes Anderson is a recidivist. The last time he blazed through the Southwest, the law finally caught up with him in Van Horn, Texas. When the cop ran the registration and discovered Anderson had another speeding ticket besides the one he was writing, he threatened jail time. But first, he thought, lets check the trunk to see what kind of contraband this scofflaw is running across state lines.

In the trunk, the cop found a portrait of Herman Blume, the character played by Bill Murray in Andersons latest film, Rushmore . The painting anchors the films opening shot. In it, Blume sits in front of his disaffected movie family, looking like Ted Turner on painkillers. Set against a burnt-orange curtain, the Blume family portrait lingers onscreen an uncomfortable ten seconds before the curtain pulls back and the movie starts. Clearly, somebodys meant to get the picture.

Is that that guy from Groundhog Day ? the cop asked Anderson.

Anderson replied that yes, indeed, the face in the painting was Bill Murrays.

Then I went into my song and dance, he says.

The song and dance is that point during a pullover when Anderson humbly explains that he is a movie director on an errand of vital importance to the project. In this case, say, delivering the painting to Mr. Murray himself for approval.

The cop ended up calling the judge at midnight, and I paid by credit card.

Then there was the time a couple years ago when a policeman in Tennessee pulled him over for doing ninety but knocked it down to eighty after the song and dance.

The cop was really nice. He had a great accent. He thought it was really something that we were both the same age, Anderson recalls. I thought he had some sadness about being only twenty-seven and being an authority figure.

Anderson has learned that part of Hollywoods magic is how it cools out the trigger finger of authority. The strategy in case we get pulled over, which seems like a safe bet given Andersons preferred speed, is for me to wave the tape recorder conspicuously and ask the officer if I can get the whole thing on record for the story Im doing. The cop will ask what story, and

Then Ill downplay it, like, Oh, Jeez, Im embarrassed, says Anderson. And the song and dance will be on.

Dont blame him for planning for the inevitable. When you drive as much as Wes Anderson does, somewhere in the John Madden range, youre bound to rack up moving violations. Its best to have a strategy. Hot chicks cry. He does his song and dance.

Today hes on the road from Los Angeles to New York, with a first stop scheduled for Amarillo, Texas. Any way you measure, its quite a haul, but its nothing compared to the larger journey of an artist who has come into his own. On that road, Anderson is somewhere between Great Expectations and Deliverance . Theres a lot of emotional investment in how he negotiates this stretch, and not just his own. Many critics appear ready to anoint him as a favorite son. Some are even saying that Rushmore , just his second feature following the critically praised but largely ignored Bottle Rocket , marks his rise to the top of American filmmaking. Rushmore s limited showing in December for Academy Award consideration earned it a place on dozens of 1998 Top Ten lists and serious Oscar hype. Premiere magazine has gone so far as to hail the somewhat gawky, twenty-nine-year-old upstart as the heir apparent to Allen, Brooks, Lubitsch, Sturges, and Keaton. There are, though, dissenting voices in the chorus of praise, and among the naysayers, one can sense an eagerness to lash back at whatever revenge-of-the-nerds factor Andersons work represents, like New Times calling the film self-important or Time saying it delights in itself too much.