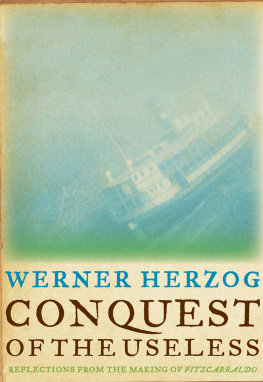

As truly as I stand here before you, someday I shall bring Grand Opera to the jungle! I will outnumber you! I will outbillion you! I am the grand spectacle in the forest! I am the inventor of rubber! Only through me will rubber become a word!

San Francisco, 16 June 1979

In Coppolas house on Broadway. Outside the wind is howling, whipping the laurel bushes. The sailboats in the bay are lying almost flat, the waves sharp-contoured and restless. The Alcatraz Light is flashing signals, in broad daylight. None of my friends is here. It is hard to buckle down to work, to shoulder this heavy burden of dreams. Only books provide some measure of comfort.

The little tower at one corner of the house, foolishly designed for meditation, is flooded with such glaring light that whenever I venture into it, I stay for only a minute before being driven out again. I have pushed the small table against the one available unbroken stretch of wall, all the rest being taken up by windows that are filled with this demented light, and on the wall I have used a sharp pencil and a ruler to draw a mathematically precise reticle. That is all I see: set of crosshairs. Working on the script, driven by fury and urgency. I have only a little over a week left of staring mindlessly at that one spot.

The air is cool, almost chilly. The wind rattles the windows so hard that I lose sight of the point and turn around, facing directly into the light, so clear and piercing that it hurts the eyes. On the Golden Gate Bridge those moving dots are cars. Even the post office at the foot of the hill offers no shelter. As I toil up the steep slope, blown leaves on the ground catch up with me. It is the tail end of spring, but the foliage is yellow and dark red. The wind whips the leaves ahead of me across the rocky hillside, and by the time I reach the top, the fist of the void has swept them away. Once more, despite all my attempts at fending it off, a shuddering sense creeps into me of being trapped in the stanza of a strange poem, and it shakes me so violently that I glance around surreptitiously to see whether anyone is watching me. The hill becomes transformed into a mysterious concrete monument, which makes even the hill take fright.

San Francisco, 17 June 1979

Coppolas father plays me a tape of his opera. As he listens, his face takes on an entirely uncharacteristic expression, chiseled, stern, and intelligent.

San Francisco, 18 June 1979

Telegram from Walter Saxer in Iquitos. Apparently things are looking very good, except that the whole situation might collapse from one moment to the next. We are like workmen, appearing solemn and confident as we build a bridge over an abyss, without any supports. Today, quite by chance, I had a rather long conversation with Coppolas production man. Over a hamburger and a milk shake he tried to convince me that he would take the projects fate in hand. I thanked him. He asked whether that meant thank you, yes or thank you, no. I said thank you, no. Coppola is not completely back on his feet after a hernia operation. He is displaying a strange combination of self-pity, neediness, professional work ethic, and sentimentality. The office on the seventh floor was trying feverishly to get a hospital bed delivered and set up in the mixing studio, and another one in some other location. Coppola did not like the pillows and complained all afternoon about the various kinds that were rushed to the spot; he rejected every one.

Los Angeles, 1920 June 1979

Executive floor of 20th Century-Fox. It turns out that no proper contract has been signed between Gaumont, the French, and Fox. The unquestioned assumption is that a plastic model ship will be pulled over a ridge in a studio, or possibly in a botanical garden that is apparently not far from hereor why not in San Diego, where there are hothouses with good tropical settings. So what are bad tropical settings, I asked, and I told them the unquestioned assumption had to be a real steamship being hauled over a real mountain, though not for the sake of realism but for the stylization characteristic of grand opera. The pleasantries we exchanged from then on wore a thin coating of frost.

In the evening off to the cinema, where Les Blank cooked for the audience watching his films; he calls these performances smell-around . For the first time I saw the tattoo on his upper arm, two masks on strings: death laughing and death weeping. I could not stay for the end of the last film because my flight was leaving at midnight, a wretched affair with stops in Phoenix, Tucson, San Antonio, Houston, and Miami; the stewardesses, who had to put up all night with an impossible first-class passenger, call this flight a milk run .

Caracas, 21 June 1979

No one came to meet me. My passport was confiscated immediately because I had no visa; allegedly they will return it to me when I leave. Several men who looked German were standing around expectantly, scrutinizing the incoming passengers, but I did not have the nerve to approach them.

Caracas, 22 June 1979

Caracas, Hotel vila. Slept a long time, woke up quite confused. I must have had horrible dreams, but do not remember what they were. There is no running water; I had wanted to take a long shower. I am keeping Janouds money with me; I have a feeling things get stolen in this hotel.

The morning meeting with filmmakers was lively. I saw a bad feature film and lowered my expectations to a flicker. Caracas caught up in a frenzy of development. Nasty little mosquitoes are biting my feet. It rained heavily in the morning, and the lush mountains were shrouded in billows of mist, which made me feel good. The taxi drivers here are not to be trusted. I have not eaten all day. Signs of Life is playing; the guards at the entrance are bored. There is a melancholy peeping in the trees; I thought it was birds, nocturnal ones, but no, I was told, they were little tree frogs.