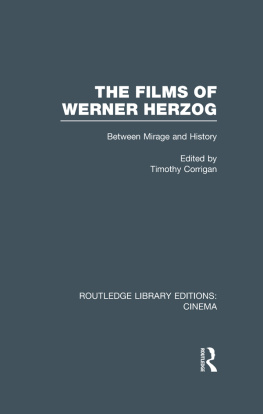

ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS:

CINEMA

Volume 8

THE FILMS OF WERNER HERZOG

First published in 1986

This edition first published in 2014

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1986 the collection as a whole, Methuen & Co. Ltd and Methuen Inc.; Individual chapters, the respective authors

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-415-83865-8 (Set)

eISBN: 978-1-315-85201-0 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-415-72678-8 (Volume 8)

eISBN: 978-1-315-85586-8 (Volume 8)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this book but points out that some imperfections from the original may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

First published in 1986 by

Methuen, Inc.

29 West 35th Street, New York NY 10001

Published in Great Britain by

Methuen & Co. Ltd

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

The collection as a whole

1986 Methuen & Co. Ltd and Methuen, Inc.

Individual chapters 1986 the respective authors

Printed in the USA

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

The Films of Werner Herzog.

Filmography: p.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Herzog, Werner Criticism and interpretation I. Corrigan, Timothy

PN1998.A3H443 1986 791.4302330924 8612430

ISBN 0 416 41060 X

0 416 41070 7 (pbk.)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

The Films of Werner Herzog: between mirage and history.

1. Herzog, Werner Criticism and interpretation

I. Corrigan, Timothy

791.4302330924 PN 1998.A3H4/

ISBN 0 416 41060 X

0 416 41070 7 Pbk

For the Corrigan family

Contents

Timothy Corrigan

Jan-Christopher Horak

Amos Vogel

William Van Wert

Gertrud Koch

Dana Benelli

Brigitte Peucker

Judith Mayne

Ttiomas Elsaesser

Eric Rentschier

Alan Singer

Several organizations provided very important assistance as this book was being researched and assembled: New Yorker Films for screenings, Temple University for a grant-in-aid, and the Museum of Modern Art Film Stills Archive (Mary Corliss in particular) for the stills used. Two essays in the volume are reprints and one a revised version of a previous article. I am grateful to the following individuals for permission to use that material: Sigrid Bauschinger (Film und Literatur: Liter-arische Texte und der neue deutsche Film), Arnos Vogel (Film Comment), Richard T. Jameson (Movietone News). Antje Masten and Mercedes Pokorny helped considerably with the necessary translations; Rick Rentschler has, as usual, been a rich and much appreciated source for ideas, debate, and facts about Herzog and his films; and Robin Nilon was my extremely valuable research assistant. To Marcia Ferguson: thanks for everything else.

A perspective always producing itself and always refusing the position it produces (Fata Morgana)

Producing Herzog:

from a body of images

Timothy Corrigan

We have to articulate ourselves, otherwise we would be cows in the field.

Werner Herzog

Enigmas, flying doctors, ecstasies, fanatics, dwarfs, sermons, wood-chucks, and phantoms: the perverse menagerie of images and abstractions that form the body of Werner Herzogs mesmerizing and exasperating films. Eating ones shoe: the raw emblem of a critical response to filmmaking, offered by a filmmaker who hopes to rescue the world with images, while claiming that film is not the art of scholars, but of illiterates (Greenberg et al., 1976, 174). Indeed, the last surprise should be that Herzog and his films, perhaps more than the films of any other contemporary director, suffer from the very excessive-ness which distinguishes them and their histrionic director, distorted equally by extreme adulation and extreme condemnation.

In many ways, the most demanding challenge of these films is therefore not their purported density or idiosyncrasies but the difficulty of negotiating and mediating the extremities that they represent and provoke. Fascinated by images of outsiders, iconoclasts, and strange other worlds, various audiences on university campuses and beyond have, since the early 1970s, turned to Herzog as the latest freedom from the dull round of commercial cinema. Yet, as part of that difference and distinction, these audiences have also discovered the guilty trace of a shared regression to adolescence and childhood. Along with the startling rebellion Herzogs images represent for many, these same films carry the aura of romantic naivet and self-absorption which tends to mark them as little more than Hollywood fantasies disguised as high seriousness and to prompt an equally reactionary dismissal of them. As Eric Rentschler has recently remarked, critics have, by and large, not found a way out of this hermeneutical impasse nor have they begun to perceive it as a problem worth their attention (Rentschler, 1984, 87).

That this critical impasse exists in such opposed terms is, it seems to me, neither an accident nor an unusual position in the reception of a filmmaker or film today Hollywood or otherwise. Rather, Herzogs monolithic performance of himself and his films is entirely consistent with commercial filmmaking of the last two decades, whether one points to the career of Michael Cimino or the person of Francis Coppola. At least since 1970, commercial movies have primarily been an occasion to make the real the ingenuous, to let history begin at the box-office, to discover singular genius in the most innocent ability to see things, and to play and play again the pleasures of regression and youth. For all their differences, The Cotton Club, Das Boot, and Rambo have shared a sense that history is fundamentally a stars spectacle which reveals itself through the immediacy of images; contemporary movies, from Star Wars to The Never Ending Story, have increasingly become narratives which map a course back to the future and toward the massive teenage audience outside the theater. With typically little awareness, the movies today have transformed that traditional tension between physical reality and formative image into the resolved equation of physical reality as celluloid image. More importantly perhaps, distinctions between so-called art cinema and the commercial movies start to become, at best, academic and, at worst, politically useless: Godard plans a version of

Next page