We may infer from these facts, what havoc the introduction of any new beast of prey must cause in a country, before the instincts of the aborigines become adapted to the strangers craft or power.

I t was five years ago that a friend of mine, David, returned to his home in Brooklyn from a week-long tour of the Galpagos Islands. David could not stop gushing about the primeval purity of the place, the otherworldliness of the creatures that live there. These ungodly animals, he told me, have no fear of people because of their utter isolation, the absence of human predators on this cluster of oceanic volcanoes

I listened politely as David described how he had approached a blue-footed booby on a rocky plateau, reached out to feed the ungainly bird a twig, and the thing responded with no hesitation at all, devouring the snack with the eagerness of a calf in a petting zoo. Davids eyes rolled back in his head as he talked of lying with his wife on a spit of sugar-white sand, gazing into the round, wet eyes of a baby sea lion that had cozied up next to them. It was, he said, a religious experience.

I was glad he was so moved. But I had no great urge to visit the Galpagos myself. Sure, Id heard of them. The iguanas. The tortoises. Darwin. All that. But until David mentioned his brief stay at the Hotel Galpagosthe Hotel Galpagos !I had no idea anyone actually lived in this place. The only humans I had ever encountered in the magazine spreads and books and video documentaries that Id seen in my lifetimethat weve all seenwere biologists, a guide or two, and maybe an on-camera narrator, someone like Richard Attenborough or Alan Alda.

There are the tourists, of course, tens of thousands of them each year, but they dont count. For these outdoor enthusiasts, the Galpagos are and have always been the ultimate theme park, a place where humans can step ashore from their cruise ships and walk the same lava-encrusted ground that the young Charles Darwin did nearly two centuries ago, which is essentially the same ground that thrust itself up from the ocean floor when these rocky islands first burst through the surface of the sea some five to ten million years ago, a blink of an eye in geologic time. For the ecowanderer, the Galpagos are and always have been a Holy Land.

But not for me. Ive got nothing against nature. I live in an oak-shaded house on a quiet Virginia river not far from the Chesapeake Bay. I sit on my porch in the morning and read the newspaper while watching a crabber empty his pots in the pink light of dawn. I enjoy an occasional drive up to the Blue Ridge Mountains, especially in autumn when the leaves change. I even allowed a friend to convince me one winter to join him for a three-day hike in subfreezing temperatures along a spur of the Appalachian Traila mistake I will never make again. The hiking itself was just fine, but the two nights I spent cursing and praying for the sun to rise as I lay trembling in my pathetically outdated sleeping bag were the longest two nights of my life.

The point is, I take my nature as it comes but make no inordinate effort to reach out for it. As a journalist Ive been lucky enough to see more than my share of the world. Wherever Ive traveled, from Arctic Alaska to the swamps of South Florida, the one species of animals that truly excites me is the human. Thats why I perked up when David mentioned the odd little hotel at which he had stayed on these islands.

You mean there are people who actually live there? I asked. Even better, I added, theyre odd ?

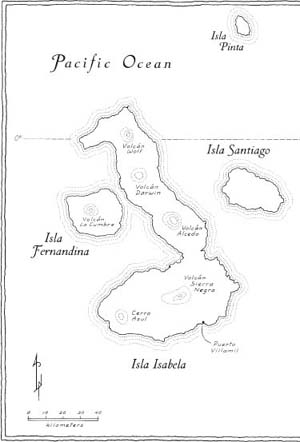

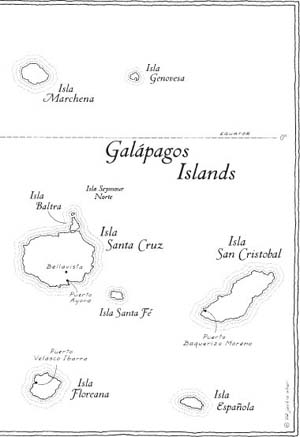

Now this indeed seemed like something to sink my teeth into. So I began some cursory researcha little poking aroundand quickly discovered theres been a lot more going on in the Galpagos lately than simply snorkeling and bird-watching. At the time, I wasnt even sure where the Galpagos are . I knew they were located in the Pacific somewhere. When I learned that they sit directly on the equator, six hundred miles west of Ecuadorthe nation that owns themI imagined that might put them roughly due south of California, maybe even Hawaii. I pulled out a map and found I was off by roughly half a continent: The Galpagos are perched on precisely the same longitudinal line asNew Orleans.

Just as surprising were news briefs I found that told of poachers during the past decade invading the protected waters around these islands in pursuit of shark fins, sea urchins, andI swear to Godsea lion penises, prized throughout Asia for their aphrodisiac effects. I read of a shoot-out between fishermen and Galpagos Park Service rangers. I read of local protesters seizing the tortoises at a scientific research station on one of the islands and threatening to kill the poor beasts if some demands were not met. Hostage tortoises. Who knew?

Who knew that the indigenous Galpagueos , the first permanent settlers on these islands, were not Ecuadorian, but Norwegiana colony of expatriate fishermen and farmers who fled their homeland in the mid-1920s to sail to a new life half a planet away?

Who knew that the ensuing half-century would bring to the Galpagos a swirling array of nomads and grifters, dreamers and hermits, a wild stew of men and women from all over the world who shared one thing in commona desire, for better or worse, to get as far as they could from the lives theyd been living. What better place for such an escape than to an honest-to-god desert island?

That is essentially what the fifty-some islands and islets that compose the Galpagos aredesert. Rocky and barren. Scorchingly hot. With cacti and lizards and no fresh water to speak of, other than the rain that occasionally sweeps down from the highlands. There are forests and farmland among some of those highlands, but that farmland is hacked out of virtual jungles, ridden with brambles and insects and volcanic stones.

Its easy to see why, when the Galpagos National Park was created in 1959, only a few hundred people lived there. Those scattered souls were allowed to remain, and the soil on which their homes stooda few seaside villages and some farms in those highlandsa mere total of three percent of the archipelagos landmass, was set aside from the Park and from the restrictions created to protect and preserve the other ninety-seven percent of the Galpagos.

That unpeopled ninety-seven percent is what most of the world knows of these islands. Its what is portrayed in the books and magazines and TV documentaries with which we all are familiar. But it was that other three percent that I became eager to explore. I was hungry to learn how the hand of man has come to shape itself here, in Darwins garden. And so, in late 1998, I booked my first flight to the islands for a one-week visit, a scouting trip to give me a taste of this place and these people. If things went as planned, this first trip would be followed by subsequent stays.