For

Bob

mio fratello

whose wrists have always been ready when

Ive leapt out into the void

THIS UNION MAY NEVER BE PERFECT,

BUT GENERATION AFTER GENERATION HAS SHOWN

THAT IT CAN ALWAYS BE PERFECTED.

Barack Obama

A More Perfect Union

Delivered at National Constitution Center,

18 March 2008

OH! DO MY JOHNNY BOWKER,

COME ROCK 'N' ROLL ME OVER

OH, DO ME JOHNNY BOWKER DO!

Johnny bowker

Nineteenth-century halyard sea chantey

LIFE, ART AND IDENTITY ARE, OF COURSE,

MUCH MORE COMPLICATED. HOW DO I KNOW?

I HEARD IT IN A BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN SONG.

Bruce Springsteen,

Letter to the New York Times Book Review

Published 31 July 2005

Contents

WALK-IN MUSIC:

SEVEN NIGHTS TO ROCK

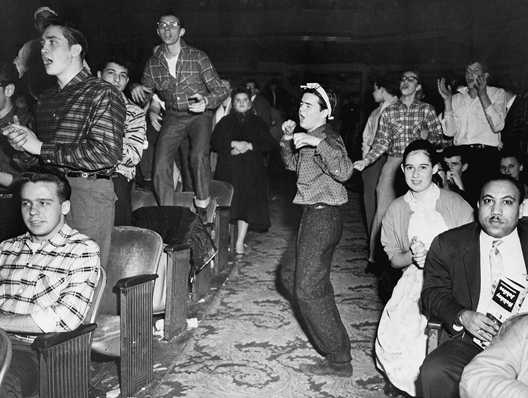

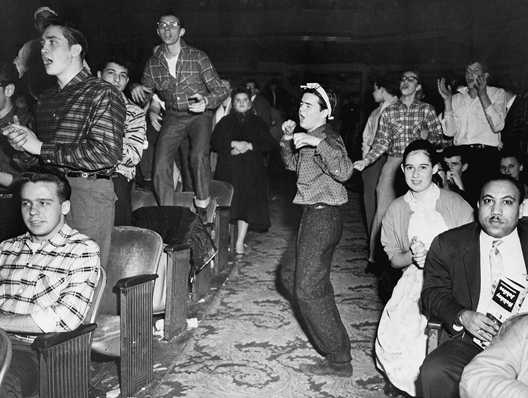

A rock n roll audience, February 1957,

New York, NY. Bettmann/CORBIS.

R OCK N ROLL IS HISTORY: SEVEN DECADES OF MUSIC, AT LEAST four decades of institutionalization, and several distinct cycles of adolescence and maturation. The bare phrase rock n roll shows up in popular music as early as the mid-nineteenth-century halyard sea chantey , but the music that we usually call rock n roll grew out of the cross-cultural stew of 1950s post-network radio. When everybody could suddenly hear everybody elses music, particularly late at night, the neat little categories into which Billboard magazine had previously tried to divide it upCountry & Western (formerly Hillbilly Music), Rhythm & Blues (formerly Race Records), and Best Selling Singles (implicitly songs favored by upper middle-class urban white people)suddenly made a lot less sense. Since that first giddy explosion of intercultural hybridity, rock n roll has been declared dead three or four times, usually when one generations music has grown stale and is just about to give way to its childrens.

For some, though, all of that music, from the 1950s to now, is part of a continuum. They can trace a direct line across all those generations from Little Richard to Ke$ha, from Chuck Berry to Muse, from Bo Diddley to Jay-Z, and from Elvis Presley to the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. For those people, rock n roll is unity: a common, ever-evolving discourse that has had its ups and downs in the increasingly fractured culture of our last half century. But if you are one of those people, you can play with the Boston Irish punk band the Dropkick Murphys one night and Stax legend Eddie Floyd another. You can play jazz with Ornette Coleman, country with Joe Ely, folk with Pete Seeger, R&B with Alicia Keys, indie rock with Arcade Fire, and even have your songs sampled by the rap group 2 Live Crew, and there is no contradiction, because all that music flows out of the same vital sources.

Conceived in this way, rock n roll is a kind of faith: a ritual and communion that replaces older forms of religion for generations that have grown skeptical of them. Like all music (and much religion for that matter), the best rock performances are in search of that elusive moment when the familiar once again becomes vital, when the rush of what is happening now is as strong as it was the first time that you heard it. is present in such moments as home and as quest , as a past tradition in which a performer and his audience anchor their actions and as a motivation that propels them through those actions into the future. How do you find God , one musically devout performer has suggested, unless hes in your heart, in your desire, in your feet? Like most faiths this side of antinomianism, faith in the power of rock is simultaneously individual and communal. Whether the specific style of the music is old-school rockabilly, neo-funk, or Viking death metal, it is by transcending the quotidian together that both artist and audience succeed in moving on up a little higher.

But even if you are one of the faithful, if you are also honest, you must admit that all too frequently such rituals can seem rote, like the thousandth time youve played air guitar on Jumpin Jack Flash or done the spelling dance to YMCA. In those cases, rock n roll is little more than nostalgia. In those cases, the music provides not vital transcendence but rather a dead longing for a golden age that always seems to exist at that exact point in the past when our independence far exceeded our responsibilities, when with a greater sense of unity, a greater sense of shared vision and purpose than it does today , as one true believer has put it a little more charitably. This is the sort of rote faith that keeps us following the same artists, going to the same clubs, and listening to terrestrial, satellite, and mobile phonelaunched radio stations so narrowly conceived that we are virtually guaranteed never to hear a song that we dont already like. This is, of course, the exact antithesis of the sweet chaos that was 1950s radio, the rude, cross-fading juxtapositions that gave birth to rock n roll in the first place.

In this counterview, rock n roll is product, and always has been. It packages acceptable rebellion for each generation until it has successfully bred the next generation of consuming rebels. It is sold to us the same way that soap is, the same way that politicians are packaged as the friend or neighbor we never knew we had. When you learn the details, it is often shocking how much the planning of a political campaign can be like the launch of a rock album, and vice versa. As the generation that embraced rock n roll at its outset has grown first to voting age and now to golden-ager status, the association of musicians and their songs with specific political campaigns has become its own little subindustry. Politicians and their staffs frequently seek rights to songs that their authors protest do not embrace those politicians values. The ensuing disagreements say a great deal about both popular music and politics, not to mention the visions of society that inevitably underlie both fields.

For our most popular music is not just product, anymore than it is just faith. Despite what those postWorld War II parents may have thought the first time they heard Long Tall Sally or Summertime Blues, rock n roll is also thought, thought as deep as its authors words and feeling can make it. It may begin with a vision of what makes for a great Saturday night at the club, but it extends as its artists and audiences mature to a larger vision of what makes for a good society. Do we come together tonight because of what we have in common, or because of what makes us different from the people outside? Does the bands frontman tell us what to think or do, or are we in the audience the ones who call the tunes? Are we each dancing for ourselves, or do we all dance together? Are the best nights of our lives ahead of us or behind us? We embrace certain musicians, as we embrace certain politicians, because they echo and anticipate our own evolving worldviews. [A] , as cultural critic Raymond Williams once suggested, in its place and time, speaks from its own uniqueness and yet speaks a common experience; speaks in a work in language, in a common language, that in its shaping becomes its own but is still common, still connects with others.

Since the 1970s, it is hard to think of an American popular musician whose songs and vision have been embraced as widely as Bruce Springsteens. Like rock n roll, his career is supposed to have been dead and buried three or four times, but he has reemerged again and again as an artist whose work is a touchstone for many who have very little else in common. He is a widely popular artist in a postmodern, niche-ridden age that is supposed to have outgrown such figures, and he consistently speaks to a continuum of popular music from the 1930s to the present that goes directly against the grain of our self-consciously alternative culture. In Thunder Road, one of Springsteens most famous and beloved songs, the music that the characters hear is familiar and conventional. Its Roy Orbisons Only the Lonely, pure product, mere nostalgia, already fifteen years old back in 1975 when Springsteen wrote his song. But that commercially familiar music nevertheless serves as a call to action for his characters, rather than as an excuse to remain in generationally subdivided complacency.

Next page