For Dylan May you always carry the fire.

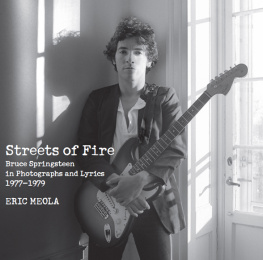

Thanks a million to Richard Anderson at Cherry Red, Mike Appel, Jo Ashbridge at Wrasse Records, Eric Bachmann, Dan Bern, Tom Bridgewater at Loose Music, Tommaso Buzzi, Anna Canoni at the Woody Guthrie Foundation, Laura Cantrell, Robert Cantwell, Peter Case, Rosanne Cash, Andrew and Peter Cash, Rob Chute, Norm Cohen, Judy Collins, Kevin Coyne, Bob Crawford, Katherine DePaul, Aymi Derham, Steve Earle, Mark Eitzel, Glyn Emmerson, Simon Felice, Paul Fenn, Jeff Finlin, Paddy Forwood, Jeffrey Foucault, Bryan Garman, Howe Gelb, Thea Gilmore, David Gray, Gaby Green at GreenGab-PR, Kenneth Green, Sid Griffin, Nora Guthrie, John Wesley Harding, Melissa Haycraft, Claire Horton at Richard Wootton Publicity, Brian Hultgren at Maine Road Management, Bill Hurley, Tennessee Jones, Robert Earl Keen, David Michael Kennedy for his magnanimity and the most iconic Springsteen photos ever, Kevn Kinney, John Lennard at Fullfill, Julius Lester for pointing out the difference between the Sixties folk revival and the topical song movement, Samuel J. Levine, Vini Lopez, Sarah Lowe at Fifth Avenue PR, Will McCarthy, Tom McCrae, Michael McDermott, Sean McGhee, Editor of R2 magazine (formerly RocknReel), David Means, Chris Metzler at Dcor Records, Matt Michaelis at Ninety Miles North Publicity, Andrew Morgan, Jim Musselman, Willie Nile, Chris Norton at IHT Records, David Pesci, Andy Prevezer at Warner Music, Chuck Prophet, Mark Radcliffe, Dolphus Ramseur, Flora Reed, Tom Russell, Jim Sampas, Jim Sclavunos, Jeremy Searle, Lesley Shone at Indiscreet PR, Southside Johnny, Brett Sparks, David Spelman, who, despite my being a noodge or maybe because of it came up with the goods, Mark Spence, Maryelle St Clare, Scott Steele at EMI Music, Michael Timmins, Willy Vlautin, Sean Wilentz for finding time to answer my questions while busily promoting his own excellent tome, Bob Dylan In America, Dar Williams and Steve Wynn

Also, to Shirley, my constant companion and greatest advocate, who, at the end of every hard-earned day, gives me many reasons to believe; Francesca, alumna of Sheffield Hallam University whom I may finally have managed to impress; and Dylan, research assistant, internet publicist and teenage rock guitar god, a superstar in waiting.

CONTENTS

J udy Collins, in an interview for this book, describes Bruce Springsteen as a folk hero. I disagree. His name may indeed be imprinted on the public consciousness as, variously, an eloquent voice of blue-collar America, a percipient diagnostician of the human condition, a stadium-filling superstar who never short changes his audience, and a compassionate liberal with a lower-case l. But a folk hero is largely the stuff of myth. The veracity of the tales that enhance such a mythical reputation can only ever be challenged superficially, because that reputation derives from the long ago, before mass media demystified everything. There is no such entity as a 21st-Century folk hero, and anyone who tells you different has been suckered by the hype.

In Springsteens case, the hype is largely the work of his manager Jon Landau, who has done an impressive job of convincing compliant music journalists that his protg is a composite of Jesus Christ, Woody Guthrie, Elvis Presley and the John Wayne character in whatever John Ford film you care to think of. And those same music journalists have then done an impressive job of convincing the public that Landaus conception of Springsteen is the real deal.

Dont get me wrong, I count myself as a Springsteen loyalist. As writers in the medium of song go, he has few equals. And I dont doubt his integrity. I believe him to be a fundamentally decent man who cares about the world and the people in it. But hes also a man mindful of image and how best to project it and protect it. Landaus role in this respect should not be underestimated.

Perhaps Peter Case put it best when he said, Fortunes were made to establish Bruce as a folk hero. Its sort of the opposite of what that word suggests.

Springsteens tangible legacy will be his songs. And perhaps among these songs, the ten that comprise Nebraska will endure more than the rest. Not because of the method of the recording although undeniably the fact that it was put out pretty much as it was produced, straight from a modest four-track recording unit, invest it with an artistic purity denied those albums meticulously assembled in hi-tech studios but because it captures a writer at the peak of his evolution. Nebraska is bookended by before and after periods. In the before, as Springsteen tries to locate his own voice, every now and then he finds it, or something damn close to it, especially on parts of Born To Run, Darkness On The Edge Of Town and The River. But the voice that we now know as Springsteens voice was truly born on Nebraska. The voice of the everyman, or more accurately, the voice of the American everyman. Nebraska will transcend Springsteen, will immortalise him as a writer, because of what it says about civilisation in the range of its complexity the beauty, the ugliness, the tenderness, the cruelty, the love, the hate, the doubt, the fear and because of what it says about the loneliness that lies at the heart of all of us.

Though I was infatuated with all things Americana from a young age, Springsteen didnt really enter my orbit until my late teens. I cant honestly say why. Id seen him on RockAround The Clock, an all-night music marathon on BBC Two television, doing The River from what I later learned was the Musicians United for Safe Energy (MUSE) concert at Madison Square Garden in 1979. It must have made an impact, the melancholy of the song, the intensity of the performance (at one point he appears to wipe a tear from his eye, though it could have been perspiration) how could it not? But all caught up as I was in a Bob Dylan fixation (which has endured), I probably filed him away in my subconscious for another time.

That time came with Born In The USA. What I heard on this blockbuster was roots music given a rocknroll makeover a bunch of amped-up folk songs about ordinary lives, the kind of lives that werent really being written about in the mainstream. I was convinced that Springsteen was more than his image suggested (the baseball cap, the white T-shirt, the distressed denims and the American flag on the album cover created a redneck misapprehension among non-followers that hasnt been easy to shift), that he was a writer of considerable import, mining the seam that Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan had before him. He was one of the good guys.

I wanted to know more. And so I went back to Nebraska, the album that prefaced Born In The USA. The sonic contrast couldnt have been more stark, and yet there was a common thread that also linked it to The River, Darkness On The Edge Of Town and Born To Run. Springsteen has often referred to it as a conversation with his audience. As conversations go, its pretty heavy-duty, embracing as it does the big themes of faith and responsibility, sin and redemption. Hardly the stuff of the MTV generation. But like the best writing, whatever the idiom, such dense themes are explored through simple storytelling, the folk impulse at work.

This, essentially, was the intended thrust of Heart Of Darkness: Bruce Springsteens Nebraska. I wanted to claim Nebraska as a great American folk album, to place it in the context of what preceded it and acknowledge its importance as a stimulus for the so-called Americana movement. In short, Nebraska as something of a bridge between old and new folk traditions.

This has involved a journey into the past, to the very origins of folk music itself and, specifically, American folk music; to the appropriation of the folk song both as a social document of an evolving America, and as an agent of protest during the Great Depression of the Thirties and the civil rights struggle and the Vietnam War of the Sixties.