The Geography of Our Youth: After Born to Run

TUNE TO ANY RADIO STATION IN THE SUMMER OF 1965, and your odds were great of hearing Keith Richardss opening chords signaling Mick Jaggers frustration: I cant get no, no satisfaction! Or, just as likely, Al Koopers organ announcing a new dawn, as Bob Dylans howling wail of disenfranchisement posed a question as pertinent today as then: Awwwwwwwww, how does it feel, to be without a home? I remember hearing Like a Rolling Stone for the first time as I was driving along South Salina Street in Syracuse, New York.

I pulled into a parking lot and let the words wash over mechrome horses, diplomats, and Siamese cats. In July I drove six hours to the Newport Folk Festival to hear Dylan stun the crowd by going electric. I was reading books with titles like The Doors of Perception by Aldous Huxley. Soon, I would walk into an induction center and refuse to step over the imaginary line on the floor.

A few years later, after graduation from college, I moved to New York, where I camped out in a friends flat on the Lower East Side while trying to get a job as a photographers assistant. Studying literature wasnt the best preparation for commercial photography, but after a while I caught enough breaks to open my own studio and support myself. I devoted most of my time to photographing in my bare-bones studio on lower Fifth Avenue. A short walk away, however, was the Fillmore East, CBGB, and Maxs Kansas City.

In late 1975, Bruce Springsteens breakthrough album, Born to Run, was released. If you had caught him in the small clubs around the city and in New Jersey in those years, you knew he would become famous. Then in October he did just that, appearing on the covers of Newsweek and Time in the same week. Seldom do you have your beliefs and convictions confirmed publicly and with such authority.

Just as suddenly, his sellout/standing room only shows at The Bottom Line confirmed the brilliance of Born to Run; shortly thereafter he was off to Europe, touring London, Stockholm, and Amsterdam. With the exception of a gig at The Roxy in Los Angeles, he finished that year touring near his East Coast fan base, spending New Years Eve at the Tower Theater in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania.

Then, there was the lawsuit with Mike Appel, his first manager. And then nothing.

In the middle of 1977, I became aware that a new album was being recorded, and I heard a few lyrics from it, including a song called Darkness on the Edge of Town. When I first heard the words, I knew that Mary, the protagonists girlfriend in the song Thunder Road, had split:

Tonight Ill be on that hill cause I cant stop

Ill be on that hill with everything I got

Lives on the line where dreams are found and lost

Ill be there on time and Ill pay the cost

For wanting things that can only be found

In the darkness on the edge of town

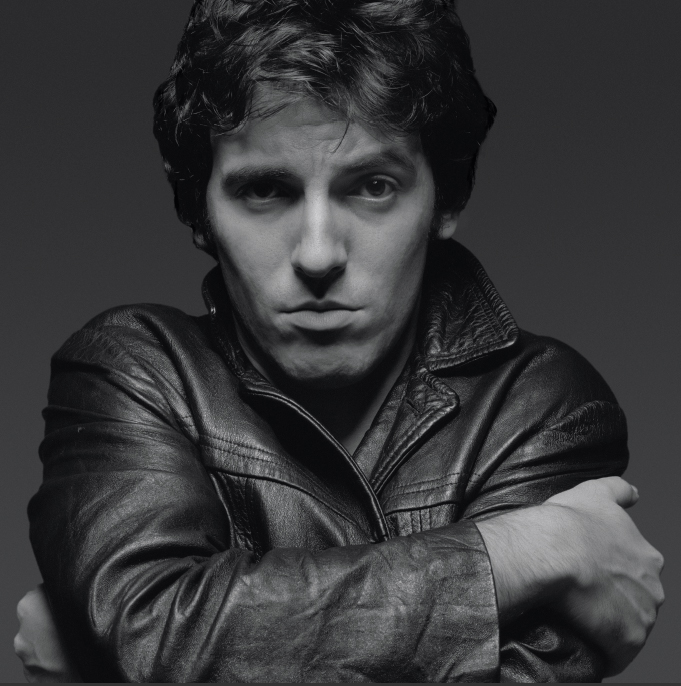

During that summer and into the fall, Bruce was holed up at the Navarro Hotel on Central Park South. I had been lucky to get the Born to Run cover photoI was in the right place at the right time. Yes, I had nailed it, but now there was a new album, and the sense that Bruce had to prove himself again was palpable. I felt that too, but I had trouble adjusting to this new Springsteen. The beard was gone, and along with it, most references to the Jersey shore. And, like most of his fans, I was stuck metaphorically in the haunts of characters such as Wild Billy and the Magic Rat, who he had so vividly portrayed in the songs on his first three albums.

When Bruce and I got together to discuss ideas for his next album, I brought along three books to get him thinking photographically. One was Robert Franks The Americans. Two others were David Plowdens Commonplace and Desert and Plain, the Mountains and the River. I knew that Bruce would be drawn to Franks book, a classic work of the 1950s that turned documentary photography as idealized in Life magazine into a gritty, personal look at the other side of the American Dream.

Plowdens work, however, is an acquired taste for most people in that it seems like a throwback to the formal photography of American vernacular architecture that Walker Evans made famous in the 1930s, and no wonder, as Evans was Plowdens mentor. Despite the urban-centric subject matter of the New Documentarians that Frank had spawned, in the 1960s and 1970s Plowden was showing us that the people of the heartland and their places still existed and still mattered. Despite being a city kid myself, that resonated with me, and the imagery is, in retrospect, echoed in many of Bruces lyrics. The very title Commonplace speaks to My Hometown. The photographs of barns, gas stations, fields, doorways, churches, and interiors, in places like Red Cloud, Nebraska, are the kinds of places we pass by every day, yet seldom notice.

In the late 1970s, several events occurred during the two years that Bruce worked on the lyrics for the songs on the album Darkness on the Edge of Town that also capture the tenor of the times. In May 1978, The Buddy Holly Story was released, with a blistering portrayal of Holly by Gary Busey. And Terrence Malick released Days of Heaven, a bleak romantic drama set in the Texas Panhandle, the follow-up to his equally evocative Badlands (1973).

Also in 1978, William Least Heat-Moons Blue Highways, a memoir of his extended road trip to forgotten towns in rural America, would affect Bruce and countless Americans who were fascinated by his portrayal of everyday people such as a barber in Dime Box, Texas. Frank, Plowden, Malick, Heat-Moonthey were all exploring the soul of the country, a side of America that also fascinated Springsteen, who declared in the first words of the first song on the album Darkness on the Edge of Town: Lights out tonight / Trouble in the heartland

In preparation for a location to make photographs for the new album, I spent days looking at maps, and then settled on a stretch of Route 80 between Salt Lake City, Utah, and Reno, Nevada. Finally, in early August, the plans came togetherwe would fly out to Salt Lake City, find an old car, and drive it across the desert to Reno. A week later, the day before we were due to leave, we were unnerved by the news that Elvis Presley diedan event which Bruce would weave into one of the dozens of songs he was working on.

Just before we headed west, Bruce got his first credit card. Prior to Born to Run, he couldnt afford one. After it, there were people on staff who just took care of things. I think Bruces lawyer had arranged for the card in case we got stranded somewhere. This wasnt the Lewis and Clark expeditionit was Bruce and me. Nonetheless, we didnt want to make it through the Donner Pass only to have our credit run out at Brendas Caf.

I remember how bemused Bruce was by that thin plastic card, the gold sheen of it gleaming in the sun as he waved it in the air and sardonically announced that now we had the world of respect,