Contents

Guide

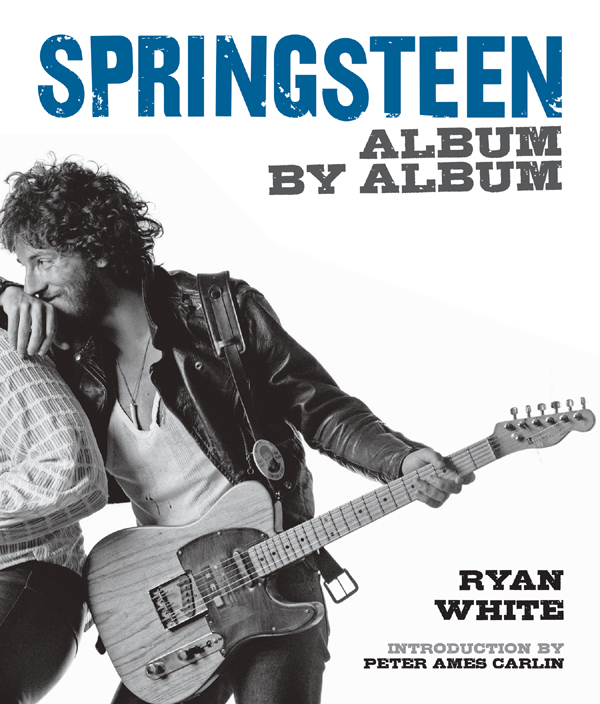

Bruce Springsteen

Album by Album

Ryan White

INTRODUCTION

by

Peter Ames Carlin

These days the world sees Bruce Springsteen in gilded light.

The voice of the common man. The personification of basic American virtues. Touched by inspiration, Springsteen sings the working-class electric: the sound of dreams born, pursued, and crushed, only to be born again.

Tales of Springsteens religious revivalesque concerts have evolved from cultist babble to widespread clich to a truism acknowledged by the president of the United States. Im the president, Barack Obama declared in 2009, but hes the Boss.

Not bad for a shy kid from a crumbling industrial town in central New Jersey. Raised poor in a hardworking but troubled family, the schoolboy Springsteen glimpsed the face of Elvis on TV and saw his own transcendence. Given an electric guitar at fifteen he practiced ceaselessly, then spent the next seven years playing with bar bands and building a reputation as the hottest lead guitarist between the Jersey Shore and the state of Virginia. In the winter of 19711972 the twenty-two-year-old packed up his guitar and a sheaf of newly written songs and took them to the cultural gatekeepers in New York City.

At first glance his ambitions seemed ridiculous. Longhaired, stick thin, and shivering in his torn jeans and a dirty sweatshirt, he could barely meet your gaze, let alone conduct a conversation beyond Hey, howya doin? But once Springsteen picked up his guitar boom. He was the king of the alley, the lucky young matador, the loser who found the keys to the universe in a rusted-up, piece-of-shit car. Also a visionary lyricist with a piercing eye into societys most fearsome crevices and a wild energy that seemed to crackle the air around him.

At least, thats how it seemed to the cadre of industry pros who quit their jobs, mortgaged their homes and/or moved across the country to take a role in the artists quest. When Springsteen landed a contract with Columbia Records in mid-1972 the same fever gripped renowned talent scout John Hammond (discoverer of Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan, et al.), label chief Clive Davis, and a feverish cult of staffers whose passion for the new artist compelled them to jump on sofas and curse out colleagues who refused to hear the true spirit of rock n roll in Springsteens craggy voice.

The doubters got the first laugh. Promoted widely as a son-of-Bob Dylan, Springsteen created no commercial ripples when his debut album, Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J., was released at the start of 1973. The funkier, more conceptual The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle failed similarly ten months later. Meanwhile Springsteen toured ceaselessly, dragging his band of Jersey Shore regularsmost of whom had played with him since they were all teenagersup, down, and across the Eastern Seaboard and the Midwest, hitting every bar, roadhouse, and small theater that would have them. Weeks, months, and then years of soul-battering, low-wage work, but increasingly important when it all got retold as part of a heros journey.

Springsteen was nothing if not wired for rock n roll heroism. Still entranced by that childhood vision of the spotlight-sanctified Elvis, he chased that promise, and commitment, into all of his shows, performing with a passion forceful enough to leave a trail of converts in his wake. More than a few turned out to be music writers whose published ecstasies helped draw more about-to-be-converts to the shows, but none could compete with leading rock critic Jon Landaus Vesuvian response to a show in Cambridge, Massachusetts in May 1974. I have seen rock and roll future, he proclaimed, and its name is Bruce Springsteen.

The future arrived a year later, riding a tsunami of pent-up media adoration fed both by the hard-eyed romanticism in the long-awaited Born to Run and the Arthurian saga of the artists quest for greatness. Springsteen, dressed for the occasion in a classic rebels leather jacket, torn shirt, and Elvis Presley Fan Club button, leans on the shoulder of saxophonist Clarence Clemons, and beams conspiratorially as his African-American brother-in-music unleashes what looks like a gut-busting riff. And from there the He-is-risen reviews, the dueling Time and Newsweek covers, a rocket ride to the number-three slot on the Billboard album charts, and almost immediately the creepy undertow of mainstream success: busted relationships, bitter litigation, and existential crises.

Locked out of the recording studio for two years due to a contract conflict, Springsteen went back on the road, furthering his reputation as a wildly inspired performer. Celebrated afresh for the battered-but-not-beaten Darkness on the Edge of Town in 1978 and then breaking through to hit singles and multi-platinum sales with 1980s party-like-youre-dying-cos-you-are The River, the revivalist rocker ventured to Europe, where the unexpected fervor came with a political edge. In the age defined by US president Ronald Reagans militaristic Cold War strategy, Springsteen presented the better-natured face of Americathe saviors of World War II rather than the imperial provocateurs of World War III.

Now living the Elvis vision hed imagined as a boy, Springsteen ventured into his hearts most haunted corners to exercise his darkest impulses in the home-recorded Nebraska. The deliberately anti-commercial move added ballast to the stars reputation for depth, which seemed particularly useful with his 1984 ascension to the filigreed ether of global stardom.

The new album was called Born in the U.S.A., and it ushered in a Springsteen re-created as a kind of everyman superherofrom his radically Herculean physique to thigh-grabbing jeans and white t-shirt to the fire-engine-red kerchief headband ornamenting his forehead. The albums dance-friendly songs shimmered with synthesizer lines, while its lead single, Dancing In The Dark, came with a glossy video featuring a beautiful young model. Plays for commercial success dont come much more obvious, and hardly ever more explosive. By the end of 1984 everyone in the world seemed to know what those Springsteen maniacs had been yammering about for so long. The Born in the U.S.A. album sold fifteen million copies at home and millions abroad while global demand for concert tickets sent the tour into the worlds most cavernous stadiums, often for multiple shows. Too enormous to be a simple rock star, Springsteen gained folk-hero proportions. More than a top-drawer rock star or the chief minister in the First Church of Rock n Roll, he was now the spokesman for the working class, the living exemplar of old-fashioned American muscle, grit, and might. And also a political symbol claimed by candidates and editorialists from every position on the partisan spectrum. Conservatives from Reagan on down noted the thundering chant that powered the albums title trackBorn in the U.S.A.! I was born in the U.S.A.! Im a cool rockin Daddy in the U.S.A.!and figured it for gung-ho, unquestioning patriotism.

Only that was the absolute reverse of what Springsteen intended, given that Born In The U.S.A. was actually about the American governments failure to care for its military veterans, rendering each chorus more bitterly ironic than the last. And the rest of the ear-friendly Born in the U.S.A. album told the whole story in the terms of shuttered factories, derelict storefronts, unemployed workers, deserted lovers, and broken-down lives. Meanwhile Springsteen studded the stadium shows with the bleakest of the