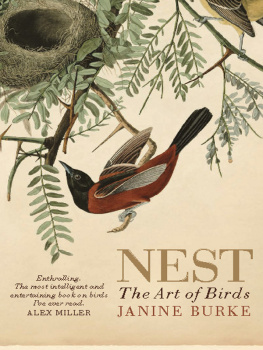

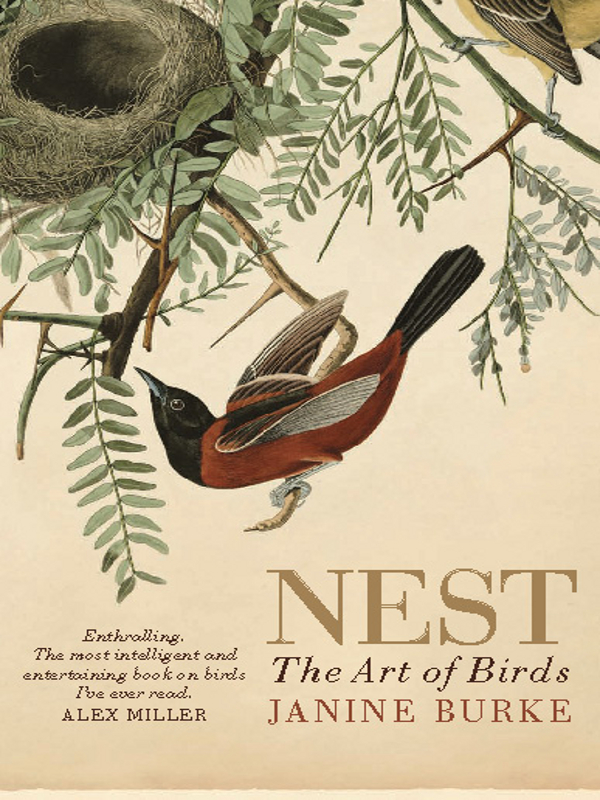

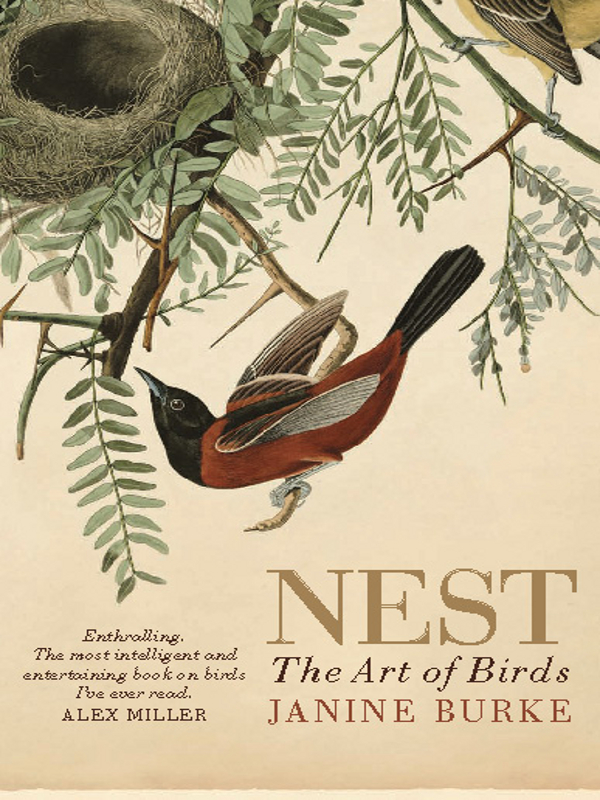

NEST

The Art of Birds

NEST

The Art of Birds

JANINE BURKE

Published by Allen & Unwin in 2012

Copyright Janine Burke 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 829 9

Internal design by Lisa White

Internal illustrations from Orchard Oriole (Plate XLII), by John James Audubon, 1831

Set in 12/18 pt Minion Pro by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Suzanne Heywood,

who also knew Sister Anthony

Contents

1

At the museum

IM A VERY AMATEUR NATURALIST. I trained as an art historian, not a scientist, and what Ive learned about birds is from observationoften of the most ordinary suburban kind, or on holidays in the countryor from reading, or watching nature programs on TV. I bought my first pair of binoculars not long ago. As my interest has grown, my eyes have become keener. On travels in Europe, America, Australia and Africa, I have watched birds with increasing fascination and admiration. Or noted with alarm their depleted numbers. There are no sparrows left in central London, for example, because the bugs the sparrows feed their babies have gone, so the sparrows had to leave too. Pigeons can endure modern metropolitan life and you will find them trundling beside you on the street, our slightly bedraggled fellow citizens. Pigeons enraged Italian writer Italo Calvino, who declared them a degenerate progeny, filthy and infected, neither domestic nor wild and bewailed that the sky of Rome had fallen under their dominion. But we should not be too disdainful of this species. Their skills as messengers contributed to the French victory against the Germans at the 1914 Battle of the Marne, and during the Second World War the British Armys Air Ministry included a pigeon section. Some of its flock were awarded medals for bravery.

We tend to take birds for granted, in the landscape or in our neighbourhoods. Yet when theyre gone, its as though theres a hole in the sky, in the air, an absence of beauty and grace, and vivid chatter or haunting cries are replaced with eerie silence. The presence of birds communicates the health of a place. They are our contact with wild nature.

The lives of birds have little to do with us directly. They recognise us as predators. Apart from that, they dont need to see us. They dont need us; we dont have anything to teach themthough we can be helpful. I live with birds quite literally: a family of Indian mynas has nested in the air vent in the wall of my study. An excellent position on the second floor, it offers unobstructed views of the surrounding terrain, sea breezes as well as shelter. Location, location, location could be the birds motto.

Common mynas, introduced to Australia from southern India in the 1860s, are generally disliked due to their aggressive behaviour. The yellow patch of bare skin surrounding their glaring eyes resembles a bandits mask. I once saw a group of them dive-bomb Prospero, my cat, on the front stairs of my apartment block. Im not sure whether it was retribution for crimes committed or whether they were merely warning him, but he did not use the front stairs again for some time. Often when Im in the yard, hanging out the washing or getting in the car, the mynas gather on the roof to shriek at me. I yell back, Im your landlady! How dare you! Ill throw you out! In fact, we have been happily cohabiting for several years. Proximity has softened my attitude. Their bad temper is only for outside, for real and perceived threats. At home, in their nest, their tones are dulcet as they quietly confer at morning and evening. Like the mynas, many bird species have adopted our structures as their own. Mynas mate for life and my neighbours seem a contented couple. They must hear me, clattering away on the keyboard, answering the phone, reading sentences aloud, cursing when the words dont flow, but I present no danger. We listen to one anothers languages without understanding but also without demur.

Where did swallows live before there were buildings? The easiest way to locate one of their elegant mud homes is to examine the eaves of your house or any other vertical construction, and there you might find, fixed to the wall and protected by an overhanging beam, a neat triangular cupped shape. You might also spot some bright eyes peering back at you or the shaft of a blue-black feathered tail. Swallows rebuild their nests, the same couple often returning to refurbish and breed after their annual migration. The site of the nest can appear perilously exposed. Theres a swallows nest attached to a wall near a cafeteria at Melbournes Monash University, where I work. By day its a noisy, subterranean, fluorescent-lit corridor, one of the universitys pedestrian arteries. The nest, about two metres from the ground, looks vulnerable; the broom of a zealous cleaner or a missile tossed by a prankster could damage or dislodge it. I approach the nest with trepidation and each time feel relieved to see it intact. Its easy to feel protective towards nests: they are such flamboyant little miracles of design.

I cant spot the swallows nests in Elsternwick Park, close to where I live, because theyre too well hidden. But I know approximately where they are because the swallows begin to circle me with dizzying speed, a tactic meant to deflect intruders. Swallows are inoffensive birds, but to have dozens of them wheeling around your feet and face can be an unnerving experience.

Next page