Prologue

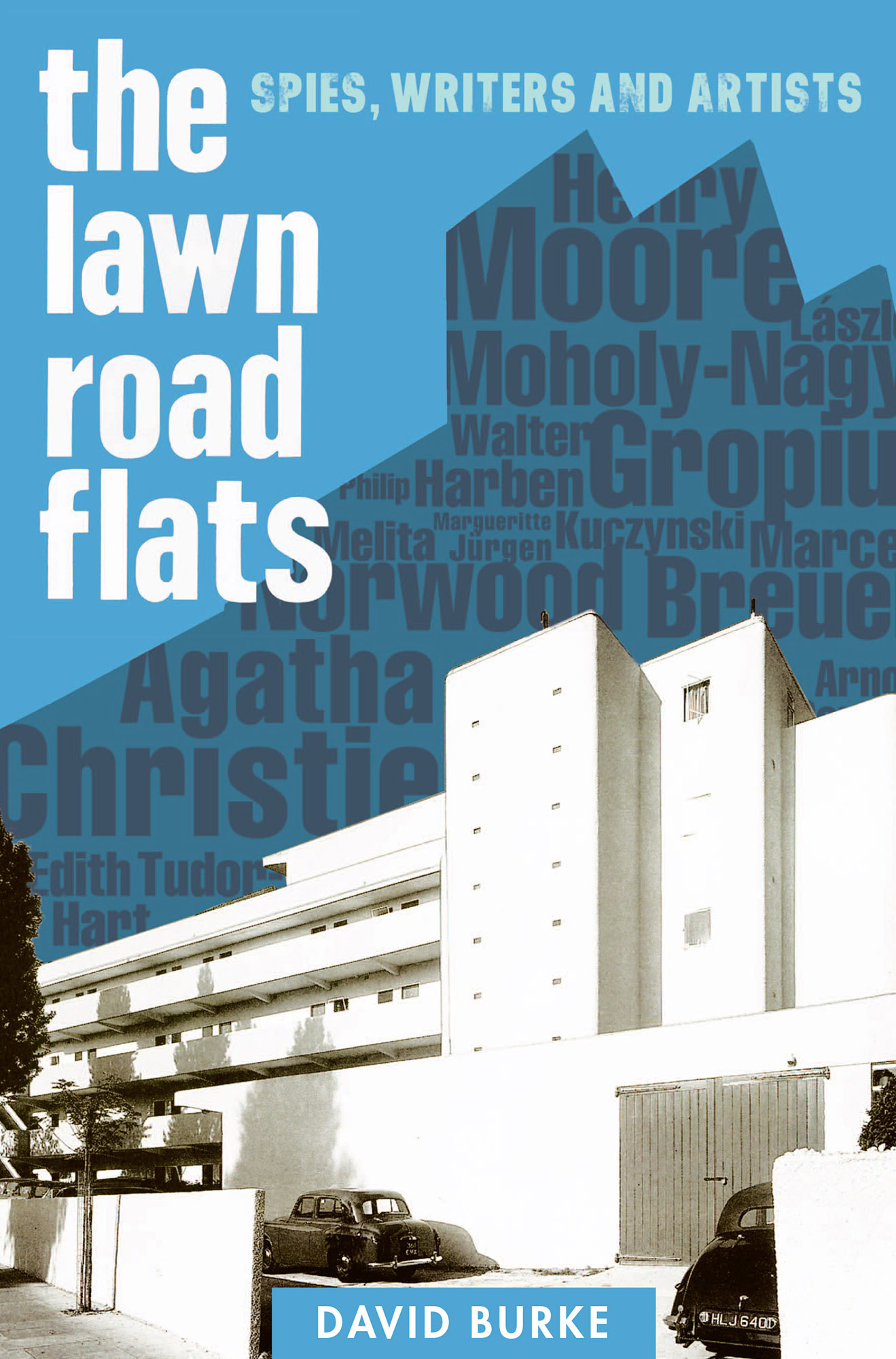

L awn Road Flats, also known as the Isokon building, comprises 32 units of equal size in Lawn Road, Belsize Park, North London. It was, and remains, a remarkable building with an equally remarkable history.

The name, Isokon arose from the architect Wells Coates use of isometric perspective in his drawings and, as the Lawn Road Flats were to be in a form of modular units, Isometric Unit Construction soon became Isokon. While this was not the first modernist building in Britain that accolade should go to New Ways in Northampton, a whitewashed, cement-rendered, two storey structure with a crested parapet, designed by the German architect, Peter Behrens in 1925 the construction of the Isokon building was the first time reinforced concrete was used in British domestic architecture.

On the face of it, the Isokon building is a curious subject for an intelligence historian but the idea for this book was sparked by a paragraph in The Mitrokhin Archive , an account of the the five Cambridge graduates who spied for the Soviet Union between 1934 and 1963, is found living in Lawn Road Flats, next door to the crime novelist Agatha Christie:

Early in 1934 Deutsch travelled to London under his real name, giving his profession as university lecturer and using his academic credentials to mix in university circles. After living in temporary accommodation, he moved to a flat in Lawn Road, Hampstead, the heartland of Londons radical intelligentsia. The Lawn Road flats, as they were then known, were the first deck-access apartments with external walkways to be built in England (a type of construction later imitated in countless blocks of council flats) and, at the time, was probably Hampsteads most avant-garde building. Deutsch moved into number 7, next to a flat owned by the celebrated crime novelist Agatha Christie, then writing Murder on the Orient Express . Though it is tempting to imagine Deutsch and Christie discussing the plot of her latest novel, they may never have met. Christie lived elsewhere and probably visited Lawn Road rarely, if at all, in the mid-1930s. Deutsch, in any case, is likely to have kept a low profile. While the front doors of most flats were visible from the street, Deutschs was concealed by a stairwell which made it possible for him and his visitors to enter and leave unobserved.

Andrew and Mitrokhin were perfectly correct, the Lawn Road Flats had a number of distinct advantages for spies, not least the site layout, which was governed by two railway tunnels running close together under the site. The London County Council () would not allow more than one storey to be built over the tunnels, which had left the architect Wells Coates very little room for manoeuvre. In the end, the south corner of the Flats marked one tunnel edge while the garage was built over the other tunnel. This meant that the building, which was long and thin, was angled to the road in such a way as to make surveillance difficult. There was also easy access to Belsize Park tube station from the rear of the Flats, which were situated in secluded woodland. Just as important, access to the Flats would have exposed any casual visitor to unwanted curiosity. Staircases at the north and south ends were the only means of entering the building. The north staircase was internal, while the south staircase was external. These were the only links between the various levels of the deck-access galleries. Once a visitor had entered the Flats it would have been extremely difficult to keep a track of their movements from Lawn Road itself, and any character on a residents or visitors tail would have been conspicuous.

As always, though, reality is less romantic than fiction and Arnold Deutsch never lived next door to Agatha Christie. In fact, Murder on the Orient Express was published in 1934, but Deutsch lived in Lawn Road Flats between 1935 and 1938, and Agatha Christie from 1941 to 1947. However Agatha Christie was no stranger to communists, nor would it seem to the numerous Soviet spies who colonised the Isokon building during her stay. Curiously enough, when she and her husband Max Mallowan, moved into Flat 20 it had been vacated by alleged communist spy, Eva Collett Reckitt, the Reckitt & Colmans mustard heiress and owner of Colletts left-wing bookshop in Charing Cross Road. And Christies bridge partner, and their neighbour in Flat 22, was the Australian communist and archaeologist, Vere Gordon Childe. It is feasible that Agatha Christie may well have spoken to the German communist agents living in the Flats or eavesdropped on their conversations in the Isobar, the bar and restaurant in the basement of the Isokon building. Certainly her only spy novel N or M? was written here and is impressive for its knowledge of spy tradecraft and Fifth Column activity in wartime Britain.

The Mitrokhin Archive was responsible, though, for exposing the activities of a quite remarkable female agent, Melita Norwood, the longest-serving Soviet spy (hitherto discovered) in British espionage history; altogether she spied for 38 years, nine years longer than Kim Philby.

When The Mitrokhin Archive was published in 1999 I was working with Melita Norwood on a biography of her father, Alexander Sirnis, who had known the Russian revolutionary, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, and Tolstoys literary executor, Count Vladimir Chertkov. At the time, I was living and working in Leeds and one weekend a month I travelled to London to take Sunday lunch with Melita Norwood at her home in Bexleyheath, to discuss the books progress. I didnt know then that she had been a spy or that she had worked on Britains atomic bomb project during the Second World War. I only found out when I got off the bus at the old National Express bus stop on the outskirts of Milton Keynes to buy a newspaper at the kiosk and saw her staring out at me from the front page of The Times under the banner headline The Spy Who Came In From The Co-op. When I eventually got to London, having missed my bus, I telephoned her and listened while she told me that she had been rather a naughty girl, that the worlds media were gathering at her garden gate, and that I had better come back next week, which I did.

When I called the following Sunday she was still in a state of shock, but cheerful. She wanted to talk and put across her side of the story as to why she did what she did. We had many conversations and on one occasion she mentioned a German professor who had escaped from Nazi Germany and was found accommodation by her mother and sister Gerty, in Lawn Road Flats. His son was still alive and living in Hampstead and would I like to go and see him? I duly made my way to Hampstead and met a very interesting man who was somewhat reluctant to speak. When I mentioned the Lawn Road Flats he was visibly shaken and said that it wasnt his father who lived there but Professor Jurgen Kuczynski and one or two of his sisters. Now this was very interesting to me, because I knew that Kuczynski had been a Soviet agent and had recruited the atomic bomb spy Klaus Fuchs to the Soviet intelligence body, the . I also knew that it was Kuczynskis sister and fellow spy, Ursula, who ran Melita Norwood as an atomic spy during the Second World War, and again for a while in the immediate post-war period.

Further research revealed no fewer than seven Soviet agents living in the Flats over the period 1934 1947 with a possible 25 sub-agents connected to the Flats or to Lawn Road itself. In 1997 the security service MI5 released its first batch of historical files, sending them to The National Archives, Kew. Based largely on a study of these Personal Files (s), and others that MI5 has released every six months since 1997, a portrait of the spies in Lawn Road Flats was painstakingly put together. It shone a fascinating light on the history of Soviet espionage in Britain and was all the more fascinating for conjuring up an image of the famous crime writer, Agatha Christie, sitting there amongst all this espionage activity writing N or M?