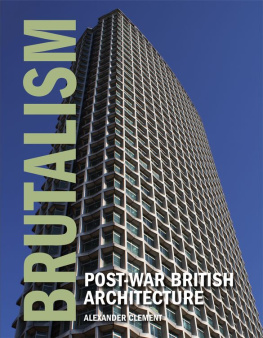

First published in 2011 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2012

Alexander Clement 2011

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 404 4

Acknowledgements

In the researching and writing of this book I would like to acknowledge the help and support of the following people: Andrea and Theo Clement, Eve Owen, Jimmy Jaques, Stephen Clarke, Christine Otterwill and Kevin McGimpsey. I would also like to extend grateful thanks to Kendal Goode and Chief Superintendent Purdie of the North Wales Police, Sasha Ricketts, Terry Brown and Mick Farrell from GMW Architects, Sue Foster at Building Design Magazine, Pam Afghan at the Ministry of Justice, Karen Robinson at the Trades Union Congress, Mark Hansford and Sally Harper at The Economist Newspaper Ltd, Nick Saffell at the Cambridge University Office of Media Relations, Delwyn Evans at Flintshire County Council and Ather Mirza at the Leicester University Press and Corporate Communications Office.

Photography Credits

The images in this book have been taken by the author, with the exception of the following for which grateful thanks go to: Darren Ashley (Chapter Hall, Truro Cathedral), Stephen Clarke (Trinity Car Park, Gateshead), Debbie Soon (New Court, Cambridge), Elliott Brown (Birmingham Central Library), Iqbal Alaam (the Chapel at Churchill College, Cambridge and Nottingham Playhouse), Steve Cadman (Cripps Building, Cambridge), Tim Eccleston (Coventry Cathedral), Colin Brooks (Engineering Building, Charles Wilson Building and Attenborough Building, Leicester University), Roger and Jane Kelly (Bernat Klein Studio), Aiden McMichael (Ulster Museum Extension), David Martyn (Clifton Roman Catholic Cathedral), Adam Kerfoot-Roberts (Halifax Building). Images of the University of East Anglia (UEA) were provided by courtesy of the University. Images of Brunel University lecture theatre courtesy of the University with grateful thanks to Sally Trussler.

As a boy growing up in Woking, Surrey, I became acutely aware of what was frequently termed the concrete jungle. The towns civic centre, central library, public swimming pool and shopping precinct, now all demolished or restyled, were built during the 1960s and 1970s in what I now recognize as the Brutalist style. The distinctive British American Tobacco building, which still stands and is now occupied by Telewest, was one of the last to be completed and is a significant late example which dominated the town and remains a well-known local landmark. At the time, Brutalism was in its final phase and was already being replaced with neo-vernacular, Dutch Barn-style civic building and was regarded , by and large, as outdated and ugly. Nevertheless , it must have planted a seed in my mind which would later grow into a great love of twentieth -century Modernist architecture, although it took many years to reach maturity.

My early interest tended to favour historicist (that is, as opposed to modernist) styles such as the Neo-classical, Queen Anne and Gothic in other words, those forms which predominated during the nineteenth century and survived into the twentieth. Modern architecture was pretty much a closed book to me until I began studying it at degree level and understood for the first time why such buildings looked the way they did. My interest in architecture expanded greatly and formed the basis of a passion I have carried with me ever since.

While I would never wish to be an apologist for bad building, my interest in architecture has led me to look at certain structures, which are widely regarded as worthy of demolition, in a different way. Brutalism is, I would have to agree, an acquired taste, but I have long held a fear that a great many important examples of British architecture could be lost to history simply because they have been misunderstood and dismissed as unfashionable and unsightly. My hope in writing this book is that I might transfer some of my enthusiasm for modern buildings to the reader so that he or she may have an opportunity to view them with a fresh eye and find something hitherto hidden in them.

Alexander Clement, 2009

The term Brutalism, when used to describe a specific type of Modernist architecture, has an uncertain origin. The Swedish architect Hans Asplund , writing in the Architectural Review in 1956, suggested that he coined the phrase in 1950 when describing the work of his colleagues Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm. The term then emigrated with them to Britain, where it was taken up by a select group of young up-and -coming architects. The first time the term was written down, though, was by Alison Smithson in 1952 in documenting a design for a new private house in Chelsea. By 1959 the word was fixed in the public and industry consciousness with the publication of Reyner Banhams book The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic.

What Brutalism describes is an uncompromisingly modern form of architecture which appeared and developed mainly in Europe between approximately 1945 and 1975. It is distinctive, arresting, exciting and, at the same time, like almost no other form of architecture before it, able to generate extreme emotions and heated debate. The use of modern materials predominates: concrete, steel and glass, although other more traditional ones were used in this period too, such as marble , stone and brick, but in a distinctively modern way. It is characterized by large, sometimes monumental , forms brought together in a unified whole with heavy, often asymmetrical proportions. Where concrete was used it was usually unadorned and rough-cast, adding to its unfortunate reputation for evoking a bleak dystopian future.

What begins to emerge to anyone studying this period is that there are three distinct phases of British post-war Modernism. I would identify these as, first, the Early period which spanned approximately 1945 to 1960. During this time most buildings were essentially versions of the pre-war International Style or of Scandinavian influence. Then between around 1960 and 1975 came the Massive period where the use of rough-cast concrete in chunky, asymmetrical forms predominated. Lastly, between 1975 and 1985 was what could be termed the Transitional period where we find the use of brick combined with concrete and less monumental forms, stepping towards what would become the Neo-vernacular.

Now that the age of Brutalism is a comfortable thirty years in the past, there is an opportunity to look back at the way this style evolved in Britain, shaping the urban landscape and imprinting its character on our geography. Like few other countries, Britain possessed the optimum political and cultural environment following the Second World War for Modernist architecture to emerge from the shadows and become part of the mainstream. How it was that Brutalism became the style of choice this book aims to explore , studying its several forms and the functions modernist architecture was put to, looking at specific examples in context. In conclusion , the book will suggest what future there is for Brutalism in Britain how the existing examples from the immediate post-war period will survive and share our spaces with new buildings both modern and vernacular and how Brutalism has found its way into the vocabulary of twenty-first-century buildings.