We hope you enjoyed reading this Free Press eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Free Press and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Thank you for purchasing this Free Press eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Free Press and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

FREE PRESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2012 by Darrell Waltrip

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Free Press Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Free Press hardcover edition February 2012

FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

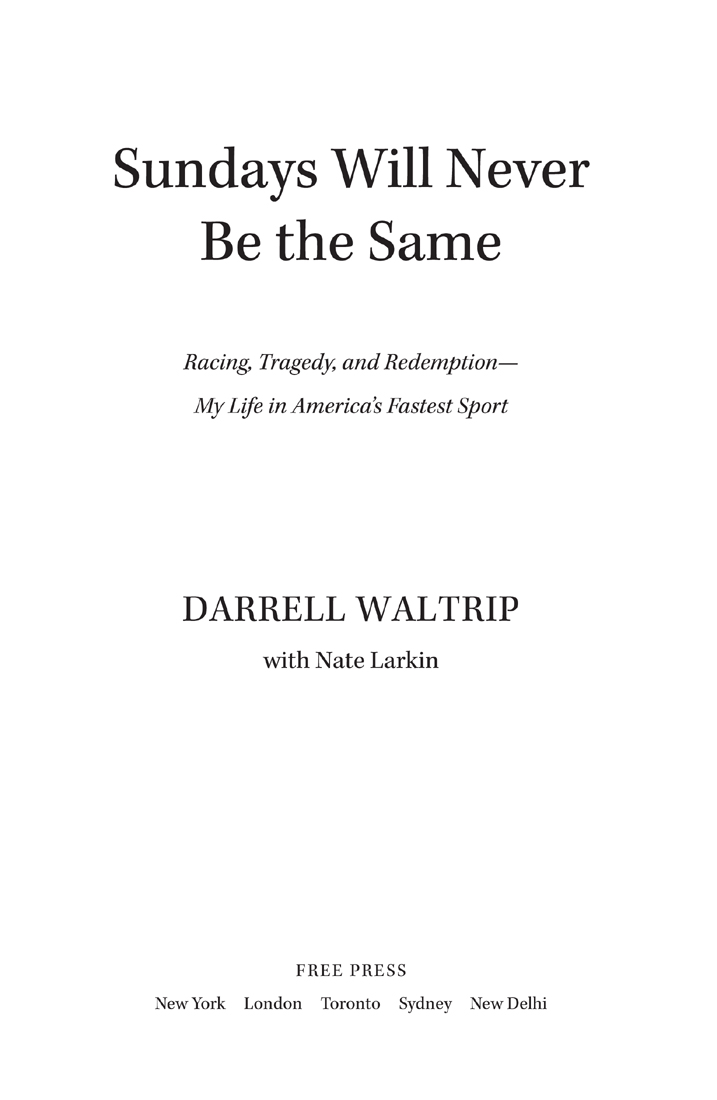

Waltrip, Darrell.

Sundays will never be the same : racing, tragedy, and redemptionmy life in Americas fastest sport / Darrell Waltrip with Nate Larkin.

p. cm.

1. Waltrip, Darrell. 2. Automobile racing driversUnited StatesBiography. 3. Stock car driversUnited StatesBiography. 4. Earnhardt, Dale, 19512001. 5. Stock car racingAccidentsUnited States. I. Larkin, Nate. II. Title.

GV1032.W37A3 2012

796.72092dc23

[B]

2011045569

ISBN: 978-1-4516-4489-0 (print)

ISBN: 978-1-4516-4491-3 (eBook)

For my wife,

Stephanie Rader Waltrip

The real hero of this story

CONTENTS

Sundays Will Never

Be the Same

CHAPTER ONE

MY NEW LIFE

H ave you ever gotten out of bed in the morning, walked into the bathroom, looked at yourself in the mirror, and said, Today things are going to change? Me neither. I dont talk to myself in mirrors. But I have gotten out of bed knowing that things were going to be different, and thats exactly how I felt on the morning of February 18, 2001.

Big-time changes were happening for me, and I knew it. People around me knew it too, and they had been saying so all week, speculating and joking with me the way race people do. Still, none of uscertainly not me, and not anybody I talked to in the days afterwardsuspected that the Sudden Change, the lightning-quick pivotal event that would burn that Sunday into our collective memory and alter the course of our lives forever, was only hours away.

On that morning the air around the Daytona International Speedway was heavy with the familiar smells of fuel and burning rubber. The track had been busy for two weeks in the run-up to the first big race of the season, the Daytona 500.

In case youre not familiar with NASCAR, let me explain. Typical events in NASCARs top series are three-day weekends, with practice laps and qualifying heats on Friday and Saturday, followed by the big race on Sunday. The Daytona 500, however, is different. NASCAR holds its Super Bowl at the beginning of its season rather than the end, and this race, its richest and most prestigious, is the final act in an extended drama of speed and suspense known as Speedweeks. This year major spectator events during Speedweeks had included a 70-lap all-star race called the Budweiser Shootout and the season-opening races for NASCARs two lower-tier series, the Busch Grand National series and the Craftsman Truck seriesplus the preliminaries for the Daytona 500.

Unlike other races, the qualifying laps for the Daytona 500 are run a week before the race, and only the first two starting positions are awarded when those timed solo laps are over. Four days later all drivers compete in one of two heart-stopping races known as the Twin 125s (nowadays their official name is the Gatorade Duels), battling for starting position in the Sunday race that will be watched by a quarter-million fans in the stands and millions more on television.

I knew the drama of Speedweeks well, but up until this morning I had always experienced the Daytona 500 as a driver. And I can tell you this: for a driver, going to the track on Sunday is like going to war. Other drivers may be your friends and colleagues on any other day, but on Sunday you are going out there against 42 other guys, and every one of them is a threat. Every one of them threatens your livelihood, just as you threaten his. When the announcer calling the race tells the television audience that drivers are battling for position on the track, thats no metaphor.

And there is a thrill in that battle that no other experience can match. The feel of the wheel in your hands, the power of 750 horses under your feet, the roar, the blur, the bump, the difficult pass, together trigger an adrenaline rush that you will never capture anywhere else. Racing is a peak experience, and the feeling only intensifies when you win.

I knew the feeling of winning the Daytona 500; Id won the race in 1989. Id won plenty of other races too, a total of 84 during my Winston Cup career. Id won the Cup Championship three times. On NASCARs list of All-Time Winningest Drivers, I was tied with Bobby Allison for third. (In the modern era of NASCAR, after 1972, I was in the lead.) But all of that was history now, because I had retired. On this Sunday I would not be walking to pit row for the start of the race. Instead Id be climbing up to the broadcast booth in my new capacity as lead analyst for Fox Sports.

My kid brother Michael would be in the race, though. Sixteen years my junior, Michael had been driving in the Winston Cup series since 1985. He had started the Daytona 500 14 times, finishing five times in the top ten, but he had never won the race. In fact Michael now held the NASCAR record for consecutive starts without a win. In 462 Winston Cup races, he had never finished better than second.

This season, seven-time Winston Cup champion Dale Earnhardt had expanded his racing team to three cars, and hed hired Michael to drive one of them. Earnhardt had an awful lot of confidence in his cars, and he liked Michael, so when people made comments about his selection of a driver whod never won a race, Dale just brushed the criticism aside. His son, 26-year-old Dale Earnhardt Jr., who had been named runner-up for NASCARs Rookie of the Year in 2000, would be driving the #8 car for Dale Earnhardt, Inc., and Steve Park would be driving Earnhardts other car, the #1 Chevy. Earnhardt would be in the race too, piloting the signature black #3 Chevy for owner Richard Childress.

Next page