Copyright 2007 by Matt Christopher Royalties, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Matt Christopher is a registered trademark of Matt Christopher Royalties, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

He wasnt going to win the race, but Dale Earnhardt was still driving hard.

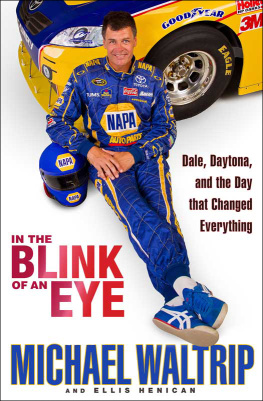

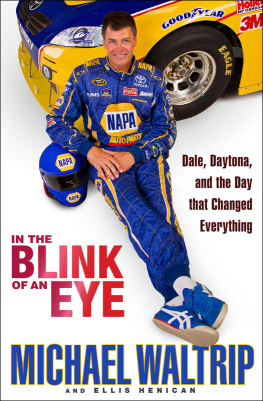

He steered his car along the straightaway toward turn four during the last lap of the Daytona 500 NASCAR stock car auto race on February 18, 2001. Earnhardt trailed the leaders. Ahead of him, Michael Waltrip and Dale Earnhardts son, Dale Junior, powered toward the finish line, bumper to bumper, fighting for first place.

It had been a long, tough race. The Daytona 500 is the first race of the NASCAR season and also the biggest NASCAR race of the year. Already, the 2001 Daytona 500 had been one of the most exciting and memorable in history. More than 200,000 fans packed the grandstand and infield to watch the race on the 2.5-mile tri-oval, a steeply banked track featuring three wide turns. Millions more tuned in on television. The lead had changed hands forty-nine times over the five-hundred-mile race, and even a spectacular eighteen-car crash twenty-five laps from the finish hadnt dampened anyones spirits, for none of the drivers had been hurt seriously.

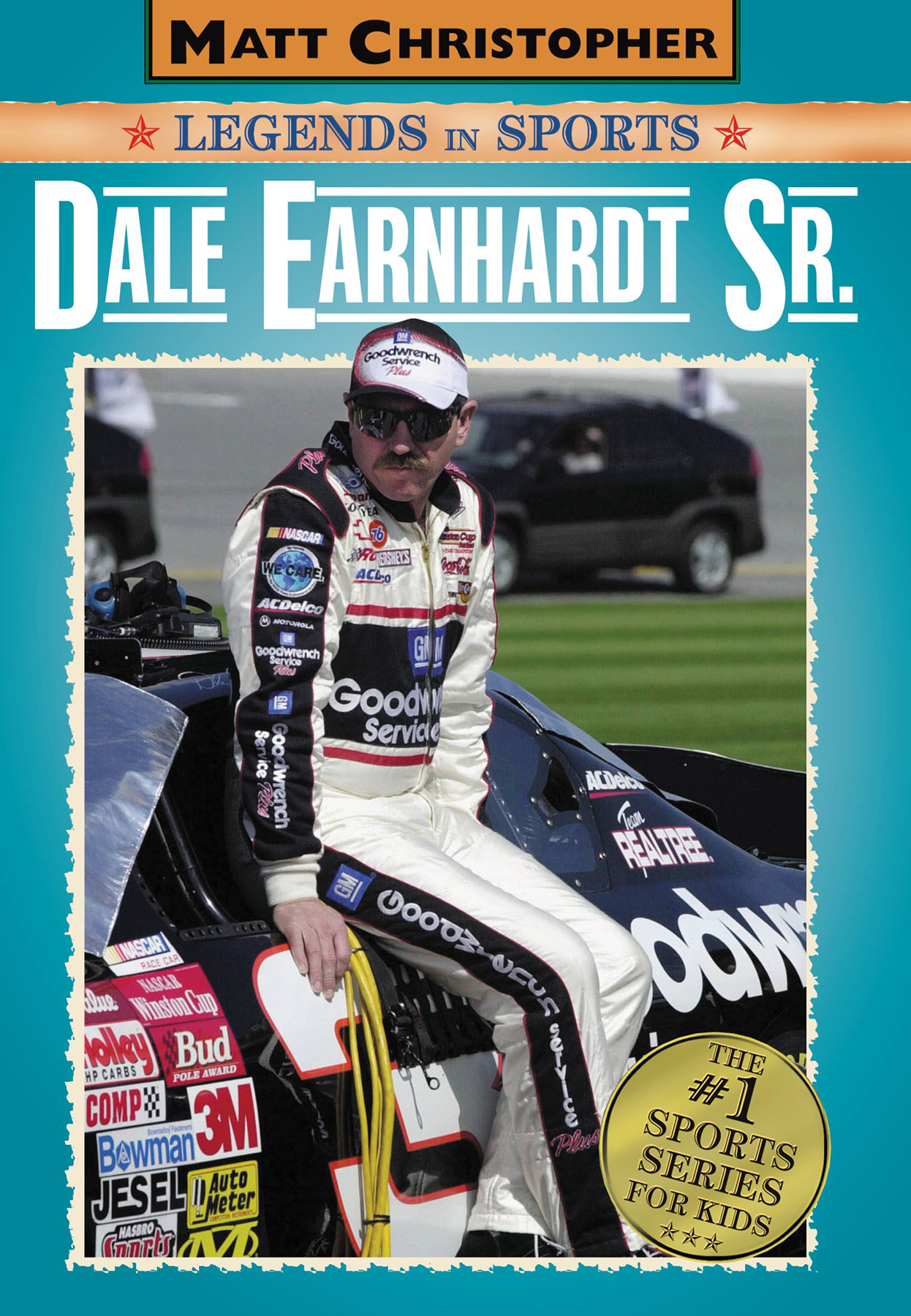

Dale Earnhardt was one of the most successful and popular drivers in NASCAR history. Since his first NASCAR race in 1975, he had won seventy-six races and earned more than $42 million. He had won seven driving championships and earned a reputation as one of NASCARs best drivers, known for his never-say-die attitude and his aggressive driving.

Despite his fame in the race car circuit, Earnhardt never acted like a big shot. In an era when NASCAR was trying to be big time, he reminded everyone that NASCARs roots stretched back to the days when drivers worked on their own cars in small garages and raced on weekends on small dirt tracks in the middle of nowhere. Like those predecessors, Earnhardt didnt race for the money but because he loved the sport.

At age forty-nine, Earnhardts quick smile and hard driving style appealed both to longtime fans and to those who had recently discovered NASCAR. His black Chevy Monte Carlo emblazoned with the number 3 was one of the most recognized cars on the racetrack.

Other NASCAR drivers looked up to him, not just for his success on the track but for the way he drove and lived. Earnhardt had started with nothing and built a NASCAR empire. He wasnt just a champion driver but also a car owner and a leader of the sport. He gave generously to charities and to his sport but refused to take credit for simply doing the right thing. As one driver put it, Dale Earnhardt was what we were all trying to be on the racetrack and off the racetrack, too.

Although Dale Earnhardt had won Daytona before, as he entered the last lap, he realized this time he would lag behind. His car just wasnt running as fast as he liked. He decided to drop back from the lead pack and join the second group of six drivers.

Just because Dale Earnhardt was backing off didnt mean he had given up. He never did. He loved racing and always tried to do as well as he possibly could. He knew that a third-place finish would mark a good beginning to the season. A driver earns points toward the season title depending on where he finishes, so each place counts. Furthermore, by backing off he had decided to do everything possible to help Dale Junior and Waltrip, blocking other cars to prevent anyone from catching the leaders.

As he approached turn four, Earnhardt was going about 160 miles an hour. The rest of the pack was gaining on him. Another driver, Sterling Marlin, was pulling up to him on the inside, and another driver, Ken Schrader, was gaining from the outside. Dale, still trying to block the rest of the racers out, was trying to stay ahead of everyone.

Thinking he was clear of Marlin, Dale turned his steering wheel ever so slightly to the left, to close the gap and squeeze Marlin out. As he did, he clipped the bumper of Marlins car.

Such minor collisions happen all the time during NASCAR races. Cars travel at high speed in extremely close quarters. As they fight for position, they often bump and brush against each other. Few cars finish a race without a few small dents and scrapes.

Most of the time, these small bumps arent a problem. NASCAR drivers are highly trained pro fessionals and know how to prevent small collisions from turning into major accidents. Still, accidents are as much a part of racing as fouls are in basketball. Contact between two people trying to reach the same goal is inevitable.

But sometimes such contact can snowball out of control.

Earnhardt had just turned his wheel when he clipped Marlins car. With that nudge, Earnhardts car began to slide sideways toward the center of the track. Earnhardt corrected it, turning hard to the right, but then the car started sliding in the other direction, toward the concrete wall bordering the track.

Earnhardt knew how to control such slides. Over the course of his career, he had been in dozens of accidents and hundreds of near misses. This time, however, something went wrong.

He may have been tired after racing 499 miles. His fatigue may have made his reaction just a little slower than normal. So many miles undoubtedly wore down his tires, making their grip on the hot track a little less sure.

Whatever the reason, Dale Earnhardt lost control of his car.

Instead of straightening, the Chevy kept turning sideways. Earnhardt slid past Marlins carand, still moving at well over 160 miles per hour, cut directly in front of another car running on the high side of the track.

Veteran NASCAR driver Ken Schrader didnt have time to react.

Bam!

Schraders car buried itself in the passenger side of Earnhardts Chevy. Locked together, the two cars hurtled toward the concrete wall. Earnhardts car struck nose-first, then both cars careened along the wall, sending up showers of sparks and clouds of smoke. Then they slid down the sloped walls of the track before coming to a rest on the grassy middle of the track.

Fortunately, the cars behind them were able to steer around the accident. Seconds later, Waltrip edged out Dale Junior to win the race. Race officials waved the checkered flag to signal a winnerthen hurriedly began waving the yellow flag to warn other drivers of the accident.

As NASCAR accidents go, the collision didnt look that bad, especially compared to the eighteen-car crash that had happened earlier. That wreck had sent cars spinning in every direction and debris flying through the air. Several cars had been completely destroyed.

Yet despite all the damage, no one had been seriously injured in the earlier pileup, thanks in large part to NASCARs regulations about safety equipment. Every driver wears a seatbelt and shoulder harness and is protected by special seats. A rollbar encases the cockpit so if the car turns upside down the roof cannot collapse on the driver. Drivers wear protective helmets to guard against head injuries and flameproof suits to protect them against fire. While accidents are common in NASCAR racing today, deaths are rare.