About the author

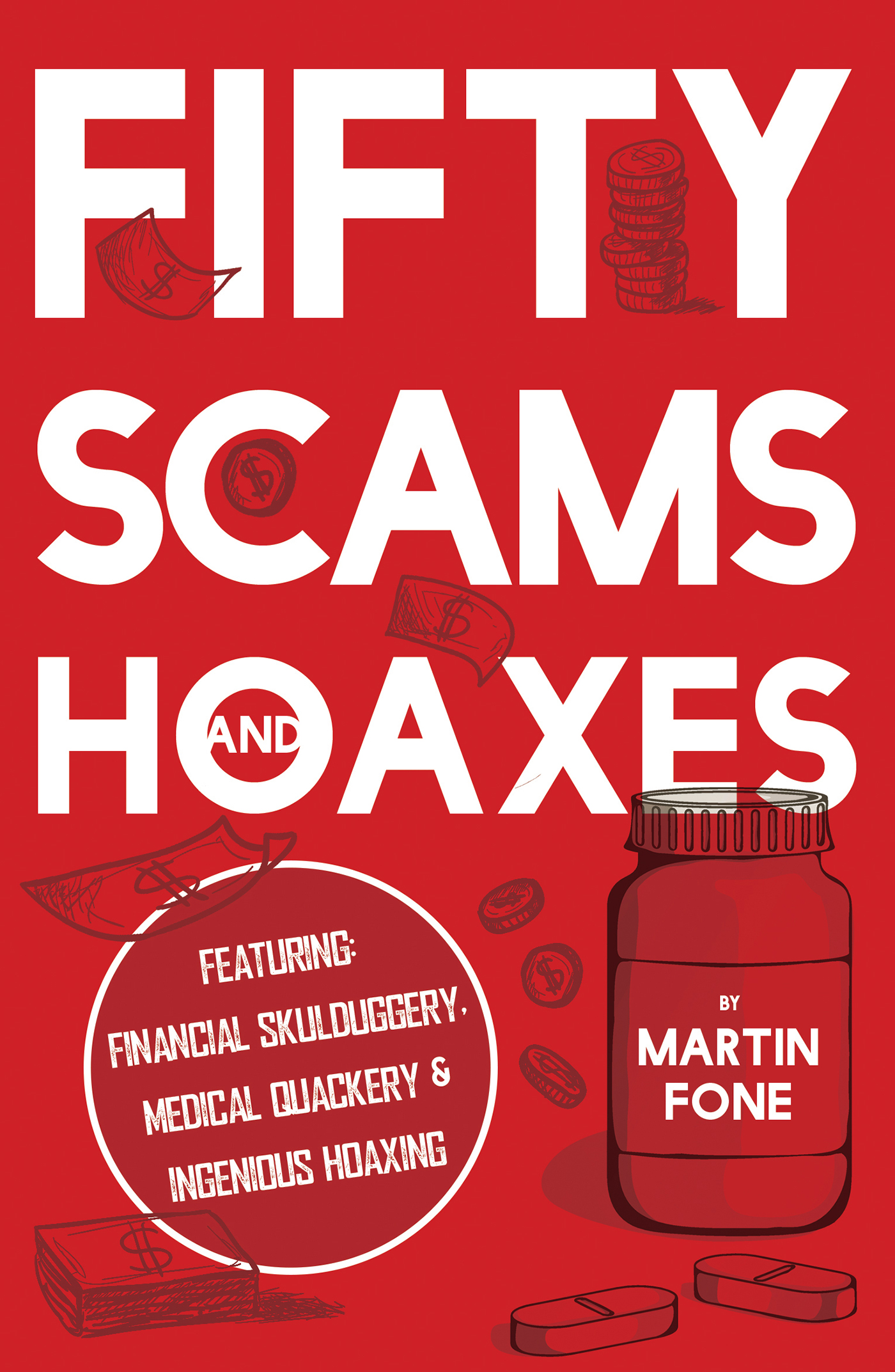

After graduating from Trinity College, Cambridge with a degree in Classics, Martin Fone started his working career as an audit assistant. However, he soon found the world of bean-counting too racy for his taste and retreated to the calmer pastures of the insurance industry. He had a successful business career, during the course of which he co-authored two books on public sector risk management, which were adopted by the Institute of Risk Management as their standard text books.

Perhaps it was his acquaintance with the murky world of the financial services industry that piqued his life-long interest in the psychology of scams and hoaxes.

Since retiring, Martin has had the opportunity to develop his interests, mainly reading, writing and thinking or, as his wife puts it, locking himself away in his office for a few hours a day. In particular, he has been blogging and writing in his tongue-in-cheek, irreverent style about the quirks, idiocies and idiosyncrasies of life, both modern and ancient.

This is the third book he has written since leaving the insurance industry behind, following on from Fifty Clever Bastards and Fifty Curious Questions , both of which, he says, are still available from all good book retailers and high-class charity shops.

Copyright 2018 Martin Fone

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: books@troubador.co.uk

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 9781789012408

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

This book is dedicated to my parents, Ray and Brenda.

I am also eternally indebted to my wonderful wife, Jenny, whose love and support made this book possible.

Contents

Introduction

The origin of the diddle is referrable to the infancy of the Human Race. Perhaps the first diddler was Adam.

- Edgar Allan Poe - Diddling: Considered as One of the Exact Sciences (1843).

I am fascinated by scams, how they are constructed, rolled out, the psychology they deploy and the final outcome. Perhaps my interest is grounded in something deeper. Maybe its the fact that most scams rely on the interplay between three of the less desirable human traits: avarice, credulity and gullibility.

Many people believe that credulity and gullibility are the same thing, but there are distinct differences, albeit of degree. Those who are credulous are willing to believe something, even in the absence of reasonable evidence, but, generally do not act on that information; whereas someone who is gullible is the easier to dupe because they are prepared to act upon such information.

To illustrate the point, if I believe a man can squeeze himself into a wine bottle, I am credulous. But if I rush out and buy a ticket, convinced that I will see a man squeeze himself into a bottle, I am gullible (see the Great Bottle Hoax of 1749, No 44).

As Stephen Greenspan noted in Annals of gullibility: why we get duped and how to avoid it (2009), what differentiates gullibility from credulity is the coupling of action with belief. Gullible outcomes, he writes, typically come about through the exploitation of a victims credulity.

This may all be a bit too sophistic for some, but what is clear is that when credulity and gullibility clash with avarice, the fall-out can be quite spectacular.

Those who perpetrate frauds typically prey on one of our two major insecurities: our health and our wealth. We like to live in good health and we want to feel that we have enough money to live comfortably. When we suffer ill-health, we like to get our hands on some drug, tincture or potion, which is going to alleviate our symptoms and restore us to rude health. We are also on the look-out for ways in which we can extend our financial assets, preferably in a way that involves as little effort on our part as possible. Unfortunately, there are some people who see these natural desires as something to exploit.

Advances in medical science are such that we tend to forget that, in the 19th century and earlier, a visit to the doctor was not only expensive but downright dangerous. Those, who had a medical problem, would often resort to old wives medicinal cures or those peddled by quacks, a term abbreviated from the Dutch noun Kwakzalver, meaning the hawker of salves, to find solutions. There was no shortage of strange potions, which claimed to be a panacea for all ills. In was not until the Pure Food and Drug Safety Act of 1906 that doctors, working in America, were forced to act in a responsible manner.

The First Epistle to Timothy (Chapter 6, Verse 10) contains the sage warning, for the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil. In the second section of this book, I provide a number of examples of the grief, mayhem and despair that greed and love of money can bring with it. I have eschewed the obvious examples of financial skulduggery. I have chosen to highlight lesser known and, perhaps, more colourful tales of financial malpractice, mainly from the 18th and 19th centuries. The old adage, if it looks too good to be true, it probably is, is one that is usually best remembered when deciding on an investment strategy for your personal finances.

Not all scammers exploit human credulity and gullibility for financial gain. The book concludes with some of my favourite hoaxes, where the perpetrators displayed mind-boggling ingenuity to test the boundaries of these lamentable human traits.

Confidence tricksters were known as diddlers in Edgar Allan Poes day after James Kenneys character, Jeremy Diddler, who appeared in the farce, Raising The Wind, published in 1805. In his analysis of diddlers and diddling Poe identified the following attributes; audacity, focus on smaller crimes, self-interest, ingenuity, perseverance, impertinence, originality, and a grin.

Across the spheres of medicine and finance, we will certainly come across examples of some or all of these characteristics. Other common features, which we will see time and again displayed in our picaresque collection of scammers include; incredible claims, extensive and creative use of advertising, which play on peoples fears and aspirations, unscrupulous business practices and, when it all goes wrong, as it often does, a propensity to flee the scene and leave others to pick up the pieces.

An enterprising financial journalist in the 19th century could do no worse than travel back and forth on the cross-channel ferry. It was packed with fleeing fraudsters!

I hope you will find the examples of the scammers art interesting there is sure to be something for everyone.

Part One

Medical Scams

The Demon Drink