At the age of seventeen Dvanov still had no calluses on his soul, nor any belief in God or things that put the mind at ease; he gave no names of his own to the nameless life that revealed itself to him. But he didnt want the World to remain unnamed, either; he expected merely to hear her own name from her own lips, rather than purposely invented pseudonyms.

A surveyor, thats what I wanted to be. I was fascinated by the men who worked on our street in their orange jackets with reflective stripes. Peering through their spyglasses they checked everything within sight, just to make sure things were indeed as they seemed.

How old was I? Ten? At school we were using an outline map to learn the capitals of Europe.

Whenever Mr Hulzebos unfurled that continent of oilcloth, it was time to buckle down. With his habitual shrug and his bumbling movements, our teacher would take his pointer from its hook a slender billiard cue with a brass strip around the end. Then, turning to face the class, he would call one of us up to the front.

The idea was to move the pointer to a dot on the map and call on a pupil. If he or she didnt know the answer, it was your turn and you could shout out Athens or Reykjavik or Helsinki. Whenever that happened I felt a tingling in my fingertips. To touch dots and have them turn into strange sounds was pure magic.

The map of Europe was flecked with red symbols circled by black lines. Cities of fewer than a million inhabitants were indicated by circles the size of a shirt button. Cities of millions were the size of a bus token. And then you had the real metropolises Paris, Rome, Berlin so packed with people that Mr Hulzebos said you could easily get lost there if no one showed you the way. Metropolises were marked by squares: they had more than a million and a half inhabitants.

Of all the squares, there were only two way out at the maps edge that we didnt have to memorise.

Those are not in Europe, was Mr Hulzeboss explanation.

But whats that one called? I asked.

Thats Moscow.

I had heard of Moscow. What I couldnt work out was why the city wasnt allowed in with the rest of Europe.

And this one? I tapped the pointer against the lonely little square even further away than Moscow. The possibility of there being another city of a million and a half people so far away was too terrifying to contemplate.

Gorky, the teacher said. The class sniggered. Gorky! It sounded like a place in a fairy tale, or the name of a planet. Jupiter, Venus, Gorky. I tried to imagine a postcard with the caption Greetings from Gorky, but it wasnt easy. What would it say on the back?

Gorky is a closed city, Mr Hulzebos said. People are sometimes sent to Gorky to be punished, and they never come back.

I love books with no pictures, just a map at the front. Show me a photo, and the magic is gone. No, unfold before me, if you will, the map of a cloister where murder has been done, or sketch the fatal route of an Antarctic expedition. Dotted lines along the front at Gallipoli? A birds-eye view of the Gulag Archipelago? Normally speaking, the map at the front works like a vaccination: by administering a minuscule dose of geographical hallucinogen to the reader before departure, you preserve him from tropical madness en route.

That, at a first glance, would also seem to apply to Kara Bogaz, the book with which Konstantin Paustovsky made his breakthrough as a Soviet writer in 1932.

I started reading it soon after I moved to Moscow as a correspondent, as part of my attempt to get to know the former Soviet Union. That I reached for Paustovsky first was not unusual: he was considered the master chronicler of the Russian Revolution, the civil war that followed and the early years of socialism. Every correspondent in Moscow dreamed of being able to send home dispatches from the front line of history the way he had.

Kara Bogaz, in Paustovskys own words, is about the annihilation of the desert. To this end, he notes, a group of enthusiastic Five-Year-Planners has been working on an industrial salt-extraction plant on the east coast of the Caspian Sea. A complex of this sort will deal the desert a fatal blow. Around it, with the reclamation of water and oil and the mining of anthracite, there will arise oases from which a systematic campaign against the plains of sand can be launched.

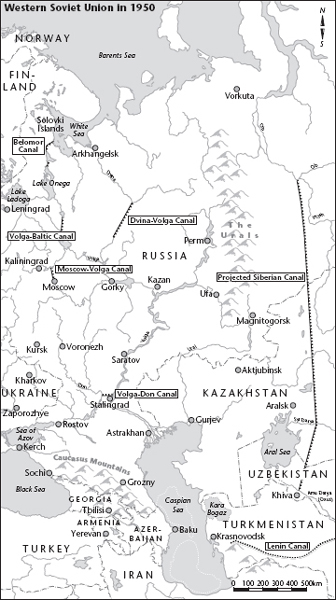

Once youre past the cover and title page, but before youve reached the first chapter, a map shows the setting in which you are about to find yourself: the bay at Kara Bogaz resembles an infant at the breast of a woman bent with care the Caspian Sea. The umbilical cord is still intact. At a glance, the surrounding countryside would appear to consist only of empty desert and nameless highlands. The closest points of reference are the Volga delta and the Aral Sea, both nearly five hundred kilometres away.

Paustovsky quotes a naval report from a lieutenant by the name of Zherebtsov, a cartographer in the service of the tsar: I hasten to report, Sire, that I have fulfilled your request and will bring with me two extremely rare birds, which I shot myself in the bay at Kara Bogaz. Our ships provisioner saw fit to mount them both and they are now in my cabin. These birds originate in Egypt, they are called flamingoes, and they bear a coat of feathers of the finest pink.

In this naval scouts wake, Paustovsky leads you on an exploration of the southernmost boundaries of the Soviet Empire.

You, the reader, are free to consult the map a hundred times as often as Lieutenant Zherebtsov might pull out his sextant to take the altitude of a star. These intermittent sightings help to keep the story on course, with a straight wake spreading behind.

Or so you might suppose. But there is something peculiar about the geography in Paustovskys book. I kept flipping back to the map at the front and couldnt stop looking at it. The bladder-shaped inland sea called Kara Bogaz seemed improbably large to me. If that bay, which Paustovsky claims has 800 kilometres of coastline, is really as prominent as the map would lead us to believe then why had I never noticed it before?

From an unemployed geologist in a Moscow metro tunnel I bought a set of four rollable maps. Their combined wingspan was two metres twenty, and they covered all eleven time zones of the former Soviet Empire. From Kaliningrad in the west to the Bering Strait before Alaska.