Table of Contents

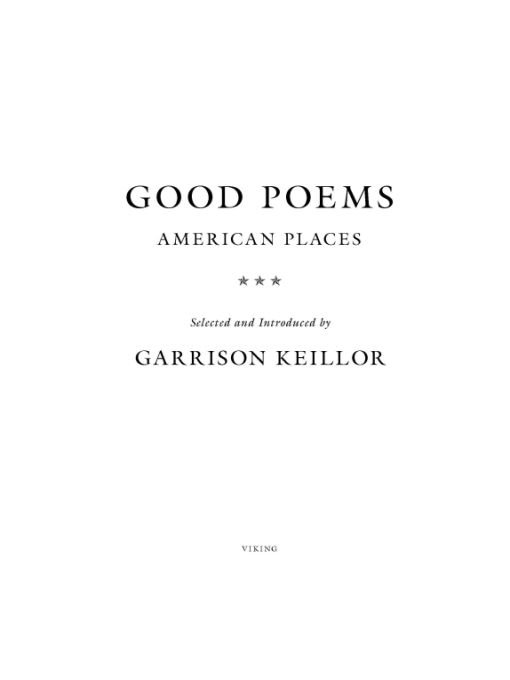

ALSO BY GARRISON KEILLOR

A Christmas Blizzard

Pilgrims: A Lake Wobegon Romance

77 Love Sonnets

Liberty

Pontoon

Love Me

Daddys Girl

Homegrown Democrat

Lake Wobegon Summer 1956

Me: The Jimmy (Big Boy) Valente Story

A Prairie Home Commonplace Book

The Old Man Who Loved Cheese

Wobegon Boy

Cat, You Better Come Home

The Book of Guys

WLT: A Radio Romance

We Are Still Married

Leaving Home

Lake Wobegon Days

Happy to Be Here

Selected and Introduced by Garrison Keillor

Good Poems

Good Poems for Hard Times

To the tourists who like to look at this vast land and mingle with the citizenry and go home and tell about it

Thanks

Francesca Cavilia managed this book from its formation in stacks of paper to its final assembly, proofing, and binding, with the help of Ella Schovanec. Kathy Roach handled permissions. Stevie Beck and Bob Ashenmacher read proof. Laura Tisdel hovered over it, fanning it with her wings.

Introduction

Over the sofa in my childhood home hung an illuminated picture of a snow-capped mountain range at sunset, purchased at 50% off at Sears. Backlit by a 20-watt bulbbright golds and greens and reddish browns, very snazzyit shone handsomely, and when guests came we made sure to switch it on. Ten feet away, our picture window looked out on the front yard, a gravel road, a cornfield beyond, a too-familiar tableau. The illuminated picture, the sort that the Great Northern Railroad put on its posters, suggested to me the Venturing Spirit of the Bold Traveler and, to my mother, the handiwork of God. How can you look at this and say there is no God? she said. I (who had not said there is no God, though I had thought it numerous times) said, And what about when you look at the desert? To base ones faith on beautiful scenery is to leave oneself open to grave doubt if you should visit Oklahoma.

We lived in unmountainous Minnesota, and every summer we six kids and two parents climbed in the station wagon and headed west across the plains to visit relatives in the hills of Idaho and Washington, Dad at the wheel, Mother in the shotgun seat, a breadboard across her lap to make baloney sandwiches on so we wouldnt have to stop for meals and waste all that money. A car trip was an emotional high point for my hardworking carpenter/postal clerk father, not that he wouldve said so ever, but nonetheless we could feel his exhilaration when he swung the car onto the two-lane concrete ribbon of Highway 10 out of Anoka and headed west. I sat in the rearmost seat and watched for classmates on the street, hoping theyd spot us as they went about their humdrum livesthe Travelling Keillorsand in case anyone was looking, I struck a pose, arm on the open window, very casual, eyes forward, breeze in my hair, like Alan Ladd looking for Apaches.

Out on the open road, Dad maintained a steady 60 mph as eastbound semis blew past like ICBM missiles and my mother shuddered at each one, anticipating a screech of brakes and a ball of fire and (I suppose) Jesus holding out His hands and welcoming us to glory. We didnt listen to the radio. No need to. We sat quietly in our places and feasted on the passing tableau, stopping for the occasional historical marker (In memory of Officers and soldiers who fell near this place fighting with the 7th United States Cavalry against Sioux Indians on the 25th and 26th of June, A.D. 1876 ) and I said to myself the beautiful names of Montana and the Bitterroot Valley, Old Woman Peak and Blue Mountain, the Sapphire Mountains, the Mission range and Rattlesnake Creek. When we finally arrived at Aunt Edith and Uncle Edmunds farm, jammed up against steep mountain slopes on the banks of the St. Joe River, our brains were teeming with imagesthe majestic buttes, mountains like the ones on our living room wall, the grim taverns in western towns, the beat-up cars, weather-beaten frame houses with junky yards, no shade trees, and dirty-faced children peering out from behind a wire fence. Bleak poverty against a backdrop of movie splendor.

We were city people and Mother dressed us nicely so we felt slightly starched and prissy among cousins who raised cows and chickens and drove tractors, but we roughed ourselves up and blended in, which children have a knack for, and one astonishing afternoon, while the grown-ups were away at prayer meeting, cousin Chuck slid over and gave me the wheel of the Allis-Chalmers, a terrifying pleasure for a city kid, age 12, driving a massive tractor up a steep twisting dirt road through stands of tall pines, the great black treads turning, the engine throbbing beneath me and, far beyond, the forested peaks mounting into the sky and the road curving into the folds of the foothills. This was not about faith in God. It was about being in an enormous moment, a cautious boy inhaling the balsam air, suddenly promoted from passenger to driver, putting my sneaker down on the gas pedal, shifting up to second gear, thrilled by the pounding pulsation of the wheel, the steep incline, Chuck hanging on to my shoulders, and if I had written a good poem (Gunning The Engine Up The Mountain, Idaho, 1954 ) I might have included it in this book, but I didnt.

This is a book of poems in which the poet simply is carried away by a particular place in America: a canyon in Arizona, the town dump, the ballpark, the barbershop, the suburban backyard, Boulder Dam, Route 66, the Big Horn Mountains, the lobby of the Algonquin, a cornfield in autumn, a snowy gravel road, a shopping mall, seat 23D on a flight to Los Angeles, a bridge over the Lac Qui Parle River, a laundromat, a town in Kansas, Eds New York apartment, a 100-year-old farmhouse, a soldiers grave in Virginia, a circle of farmers squatting and conversing and tracing figures in the dust with a stick. Carried away by some ordinary American reality that the poet stares at for a long little while and loses track of mortality, the disappointment of midlife, loneliness, the pain caused by the bad daddy or the clueless lover or the irritable children, and renders a memoir of the place in that moment. This is a lovely simple human thing. The poet (who may be famous for his multilayered recontextualized decolonized unhegemonic antipatrimonial and self-deconstructed cantos that seminars of shriveled midgets are busy pondering) takes off his Distinguished Poet hat and says, Let me tell you what happened to me this one time, and it was snowing and my lover and I lay in the tent and heard the silence, the silence was audible in the same way that anybody else would tell about a running catch in deep right field or being nibbled by minnows in a creek or some other god blessed transcendent moment arising from a specific place and time.

Kenneth Rexroth got carried away by the high Sierrashiking and camping saved him from being just another angry old San Francisco radical. May Swenson was a Utah Mormon who moved to New York for the freedom to love women and her gratitude to the city breathes in her tender snapshots of MoMA, the A train, and Eds apartment. Jim Harrison was carried away by the Arizona desert, Maxine Kumin by her hilltop farm in New Hampshire, Charles Bukowski by the Santa Anita racetrack. Other poets are transported by a hardware store and its vast glossary or a grove where ancient cars sink into the earth, a small town in Kansas, or the memory of a grandmother hurling a long arc of dishwater from a basin. And of course everyone is astonished by snowfall, and so the book includes a whole section devoted to that, as well as nakedness, a memorable experience always.