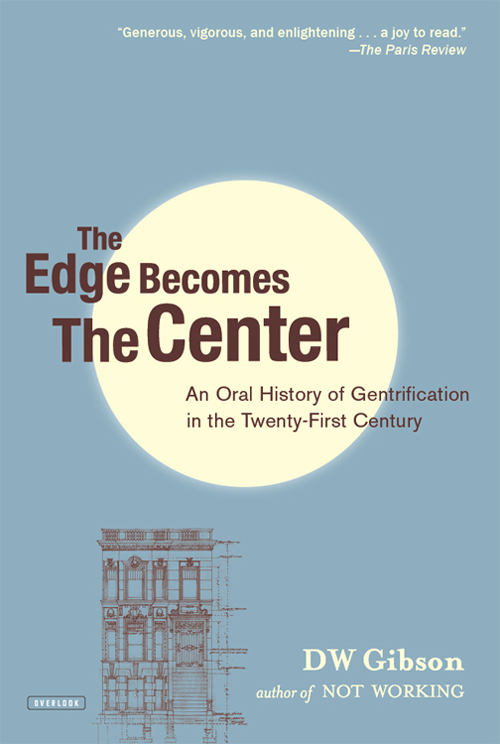

This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2015 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact sales@overlookny.com,

or write us at the address above.

Copyright 2015 by DW Gibson

Photograph on courtesy of Michael De Feo

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1187-7

For all citizens of New York Cityespecially Gigi.

I f you live in a cityand every year, more and more Americans doyouve seen firsthand how gentrification has transformed our surroundings, altering the way cities look, feel, cost, and even smell.

Over the last few years, journalists, policymakers, critics, and historians have all tried to explain just what it is that happens when new money and new residents flow into established neighborhoods, yet weve had very little access to the human side of the gentrification phenomenon. The Edge Becomes the Center captures the stories of the many kinds of peoplebrokers, buyers, sellers, renters, landlords, artists, contractors, politicians, and everyone in betweenwho are shaping and being shaped by the new New York City.

In this extraordinary oral history, DW Gibson takes gentrification out of the op-ed columns and textbooks and brings it to life, showing us what urban change looks and feels like by exposing us to the voices of the people living through it. Drawing on the plainspoken, casually authoritative tradition of Jane Jacobs and Studs Terkel, The Edge Becomes the Center is an inviting and essential portrait of the way we live now.

Opportunity in New York springs from strong neighborhoods. When we demand that big developers build affordable housing, and fight to keep our hospitals from becoming luxury condos, its not to punish the real estate industry. We do these things so the everyday, hardworking people who anchor our neighborhoods can live and work and be healthy in the communities they love. Thats how we all rise together.

I t is November 5, 2013, and Bill de Blasio stands on a stage surrounded by an exalting audience. The crowd sways to Lordes anticapitalist anthem Royals: That kind of luxe just aint for us. We crave a different kind of buzz. Victorious on this election night, de Blasio will soon be a mayor in charge of a budget with more than three billion dollars in surplus. The money started flowing into the city several decades ago, the spigot dripping steadily by the early 1990s when Rudy Giuliani and William Bratton built a police force muscular enough to frisk its way to a city free of broken windows and tagged stoops; a city with a lower rate of violent crimes, capable of seducing developers to buy up abandoned buildings. The capital surged under a twelve-year Michael Bloomberg administration, despite the fact that he took office three months after the citys two tallest buildings, its welcome beacon to global capitalism, collapsed.

Now here we are: Bill de Blasio, recently arrested while protesting the closure of a hospital, becomes the 109th mayor of New York City just as a leading real estate agent says that 80 percent of his clients are hedge funds; not individuals concerned with the quality of vegetables at the corner bodega but corporate entities who see potential in the bodegas square footage.

I set out to understand how gentrification affects lives and not far into my trip I realized the word gentrification is uselessrendered so by overuse, too broad to adequately capture a huge range of disparate experiences, contexts, and, ultimately, meanings. But no matter how idiosyncratically one defines gentrification, it is an idea that never strays far from moneyinvestment, capital moving into the neighborhood.

Ive spoken often about a Tale of Two Cities. That inequalitythat feeling of a few doing very well, while so many slip further behindthat is the defining challenge of our time. Because inequality in New York is not something that only threatens those who are struggling. The stakes are so high for every New Yorker.

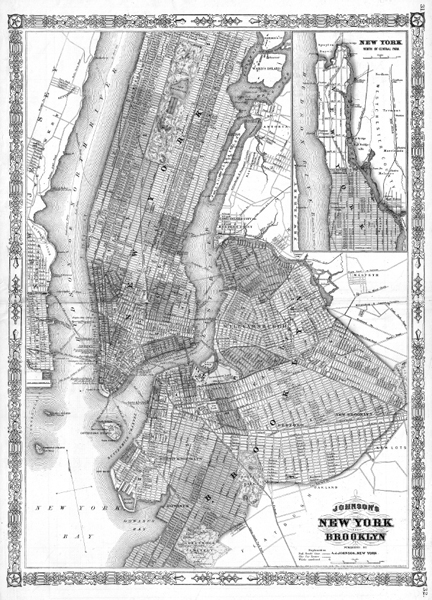

The stage where de Blasio stands is not a curtained number in a midtown Manhattan hotel ballroom; it is a temporary platform constructed in the center of a stone and brick building that was originally an armory for the 14th Regiment of the National Guard on Eighth Avenue in Brooklyn. The building has had several incarnations, a YMCA at present. This is Park Slope, de Blasios neighborhood, and thus a meaningful place to party, but more to the point: one hundred and eight mayors preceded this man and not one chose Brooklyn for his election night celebrationa fact not to be underestimated. This outer borough feels front and center.

Outside the YMCA the streets are relatively calm. The flames of the de Blasio fire only carry so far. Voter turnout for this revolutionary election was 24 percent. This is not an easy city to rile, politically speaking, particularly when the violence of gentrification that fuels the de Blasio battle cry is so subtle, less like a bullet or a blade and more like the slow encroachment of carbon monoxide, filling one building after another. The mayors neighborhood of Park Slopereminiscent of The Cosby Show and the affluent middle classis already subsumed and the vapors are advancing on the crumbling brick facades farther into Brooklyn.

I follow the vapors.

By the time I reach Lincoln Road in Prospect-Lefferts Gardens, there is no trace of the din from the de Blasio uprising. I find a forty-five-year-old man on the front porch of a towering Victorian home. It is late, deep into the night but still his snug, gray suit remains unwrinkled. His polka-dotted pocket square hasnt budged. The pinpointed fashion shaves ten years off the bachelors age; his demeanor has a confident bounce to match. Prospect Parkformed by glacial debris some seventeen thousand years ago, sculpted by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1867is two blocks away.

My names mTkalla. I always get questions. mTkalla?how do you say that? And I tell the story: My full name when I was born was Martin Kennedy Keaton. My mom named me after both Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. I was born in 1968. I used to win awards as a kid doing Martin Luther King speeches. I remember once when I was nine I did the I Have a Dream Speech and a woman in the front rowan older black womanwas balling with tears and she told my mother, I cant believe that a little boy did this speech. I performed like I was in front of Martin Luther King.

Then in 88 or 89 there was so much violence against black American men in Brooklyn. People getting beat up. People getting shot by the cops. I was doing some research regarding the whole middle passage and people getting brought here, European names being forced on them. I read Assata Shakurs autobiography and