Also by Carrie Gibson

Empires Crossroads

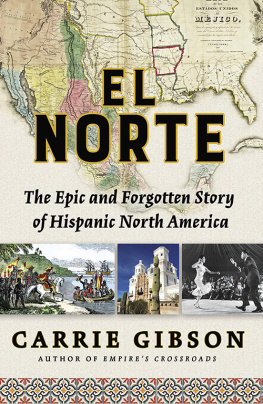

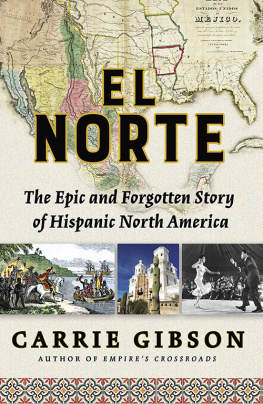

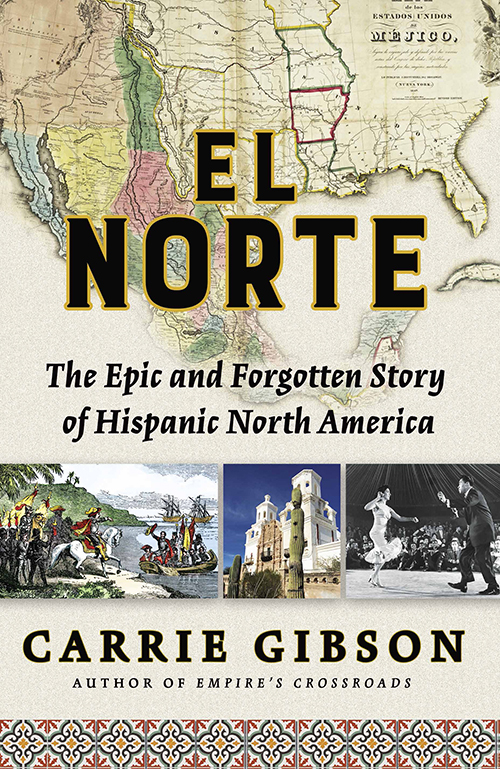

EL

NORTE

The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America

CARRIE GIBSON

Copyright 2019 by Carrie Gibson

Cover design by Gretchen Mergenthaler

Cover artwork: map alamy; dancers Yale Joel /Getty;

Mission San Xavier del Bac, courtesy of the author;

Hernando de Soto landing his expedition in Florida 1539 alamy;

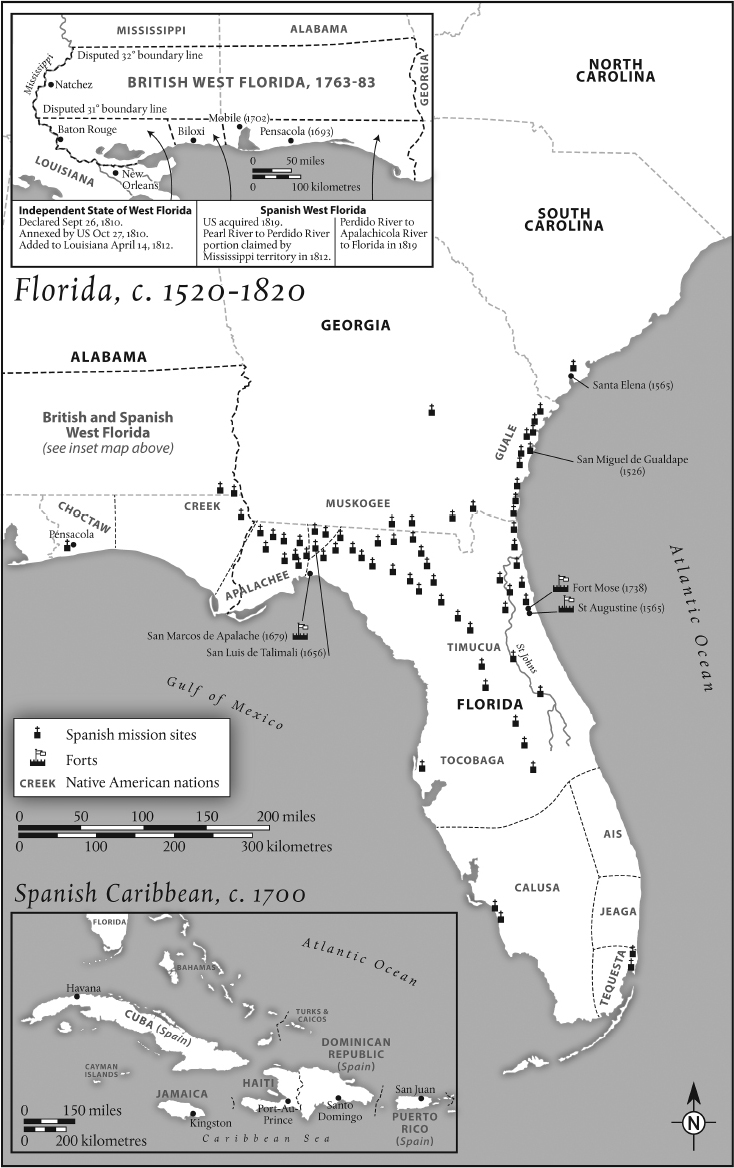

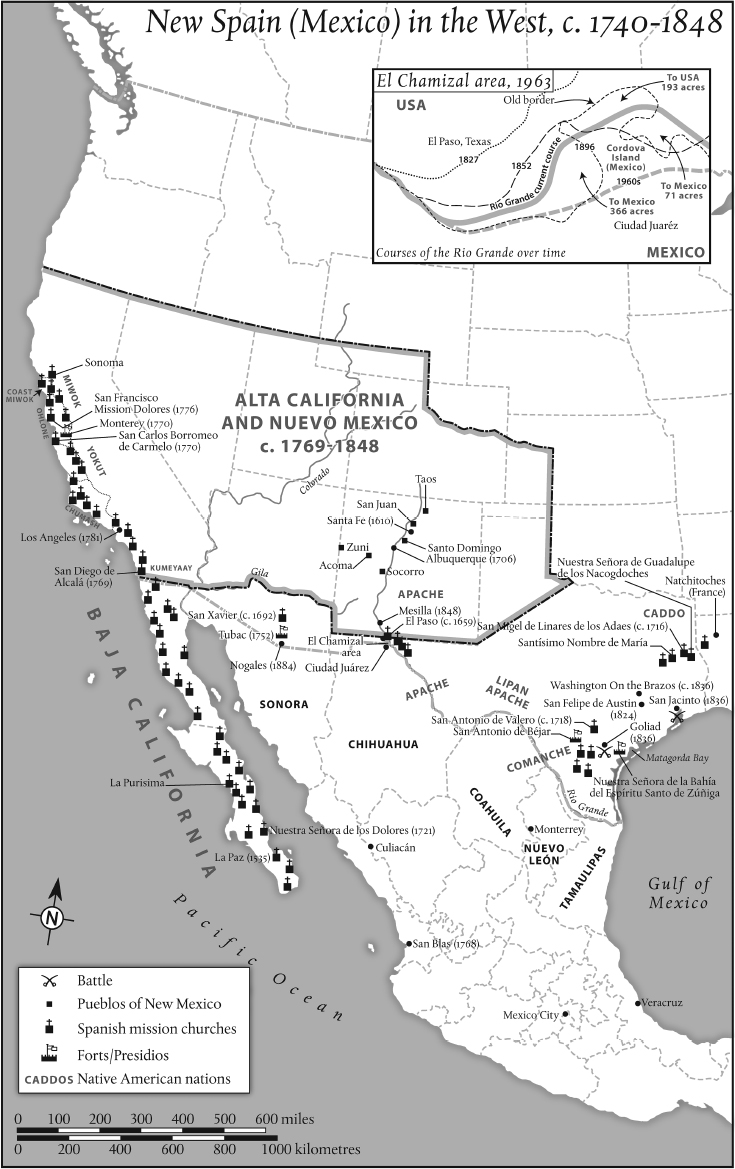

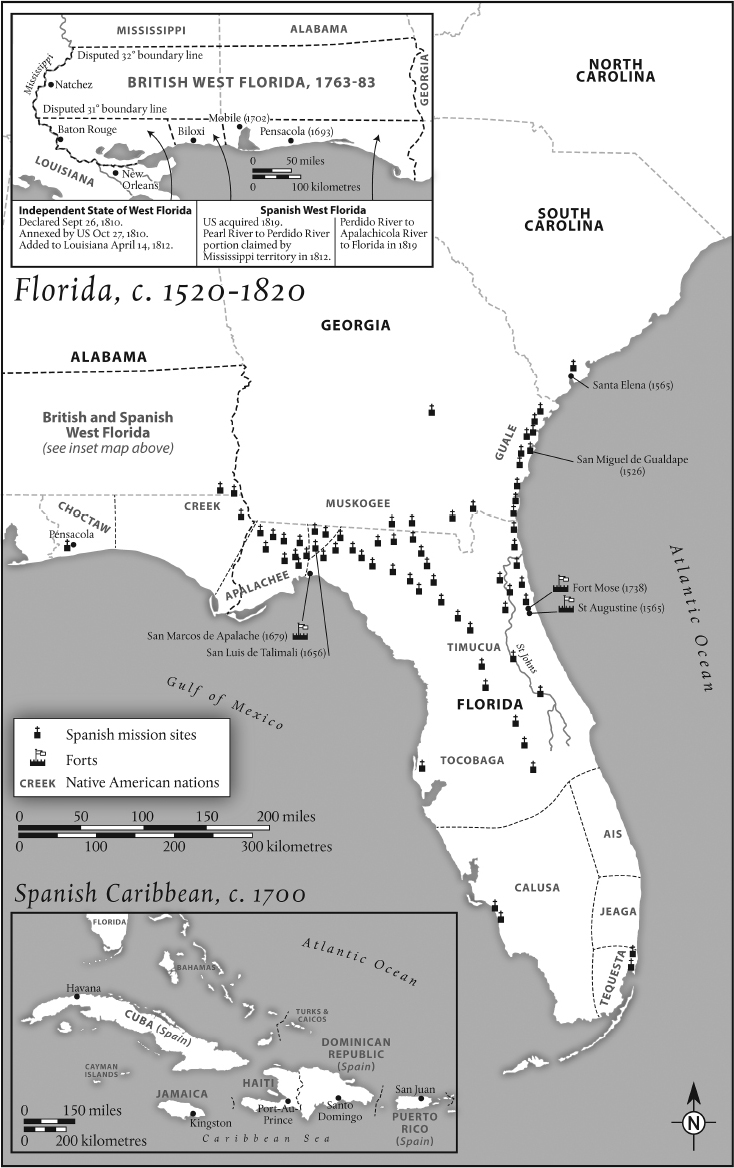

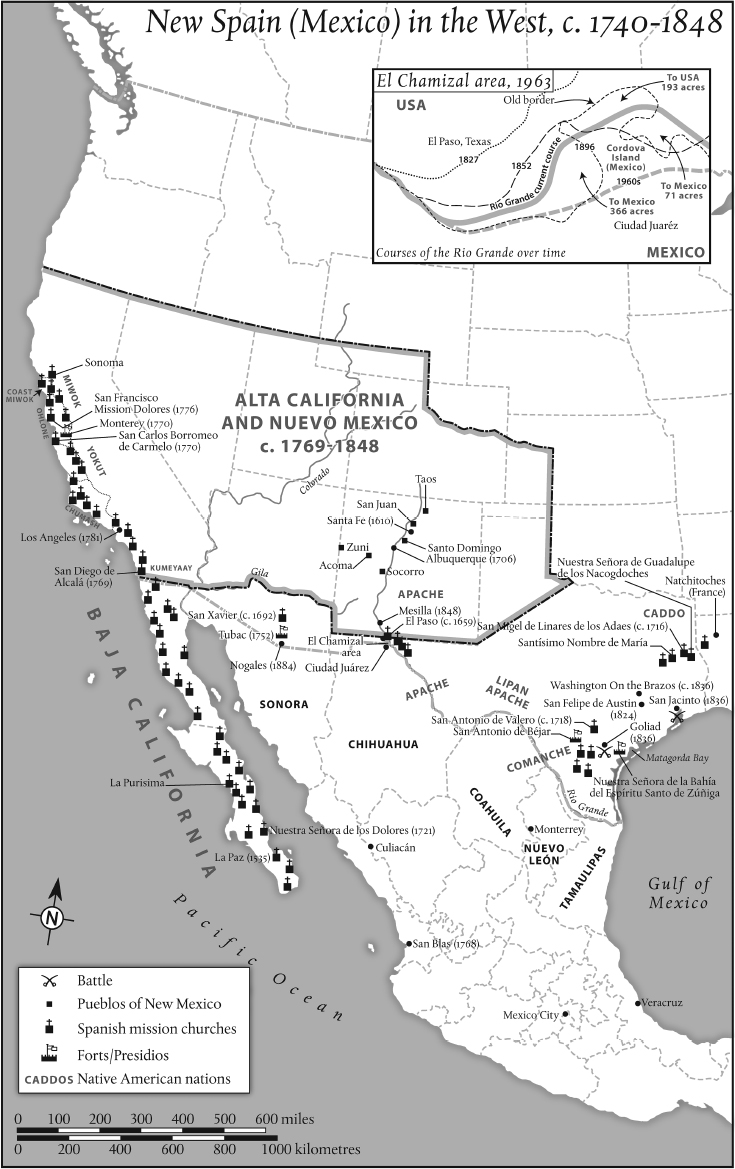

Maps by Martin Lubikowski, ML Design, London.

Image credits are as follows: : Courtesy of the author.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

FIRST EDITION

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Norman E. Tuttle of Alpha Design & Composition

This book was set in 11.75-pt. Dante with New Baskerville.

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: February 2019

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-2702-0

eISBN 978-0-8021-4635-9

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

18 19 20 21 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A Matteo: amigo, gua y hermano

How will we know its us without our past?

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

M Y JOURNEY TO El Norte was a circuitous one, taking me via England and, later on, through the islands of the Caribbean before ending not far from where I began, in Dalton, Georgia. This sleepy, mostly white Appalachian town had a dramatic transformation when I was in high school. In 1990, my freshman year, the school consisted of a majority English-speaking student body, with only a handful of people in the English as a Second Language (ESL) classes. By the time I was a senior, the morning announcements were made in English and Spanish, and the ESL classes were full. Thousands of workers and their families, mainly from Mexico, moved to Dalton to work, for the most part, in the carpet mills that dominated the towns economy. I graduated in 1994, only months after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force. We were twelve hundred miles from the border, but Mexico had come to us. Today, my old high school has a student body that is about 70 percent Hispanic, and the town is around 50 percent.

The complexity of what I experienced then and in the two decades since is what informs this book. What started in my Spanish-language classes was augmented by the arrival of people who could teach me about banda music and telenovelas. Later, I added to this mix by spending a decade researching a PhD that involved the colonial histories of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico. Finally, my experience has been filtered through two decades of living in one of the worlds most multicultural cities, London, England.

My family moved away from Dalton years ago, as have many of my high school friends, and I hadnt really thought about the town, or the question of immigration in the United States, in any serious way until the 2012 election. I was in Washington, D.C., while working on my history of the Caribbean, Empires Crossroads. As I watched and read the coverage, I was struck by the general tone of the media conversation. The way Hispanic people were depicted surprised me because the language seemed unchanged from the rhetoric of more than a decade earlier. The subtexts and implications were the samethere was little recognition of a long, shared past, and instead the talk was of border-jumpers, lack of documentation, and the use of Mexican as shorthand for illegal immigrant. It was jarring because the reality of who was coming to the United States had long been more complex, not least because plenty of immigrants and citizens have roots in all the distinct nations of Latin America. The simmering anxieties about the Spanish-speaking population that such rhetoric exposed exploded in the 2016 presidential race, during which chants of build that wall between the United States and Mexico could be heard at campaign rallies for Donald Trump. When I started this project, that election was still years away.

This book is still concerned with the questions that arose in 2012, but they are now given new urgency: there is a dire need to talk about the Hispanic history of the United States. The public debate in the interval between elections has widened considerably. The response to frank discussion about issues such as white privilege at times appears to be a vocal resurgence of white nationalism. For quite some time the present has been out of sync with the past. Much of the Hispanic history of the United States has been unacknowledged or marginalized. Given that this past predates the arrival of the Pilgrims by a century, it has been every bit as important in shaping the United States of today.

I realized, watching my Mexican schoolmates, that if my surname were Garca rather than Gibson, there would have been an entirely different set of cultural assumptions and expectations placed upon me. I, too, had moved to the SouthI was born in Ohiobecause my fathers job necessitated it. We were also Catholic, my grandmother didnt speak English well, and I had lots of relatives in a foreign country. Yet my white, middle-class status shielded me from the indignities, small and large, heaped upon non-European immigrants. Like most people in the United Stateswith the obvious exception of Native Americansmy people are from somewhere else. In fact, Im a rather late arrival. The majority of the motley European mix of Irish, Danish, English, and Scottish on my fathers side dates from the 1840s onward. My maternal grandparents, however, came to the United States from Italy in the period around the Second World Warbefore, in the case of my grandfather; and afterward, for my grandmother. The pressure to Americanize was great in the 1950s, and my grandmother, who never lost her heavy Italian accent, felt it necessary to raise my mother in English. She died before I could learn any of her Veneto