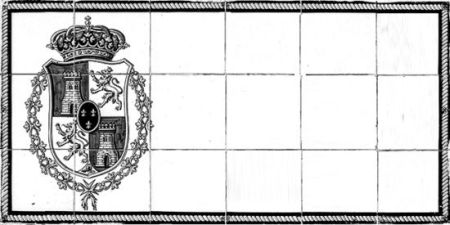

Hispanic and Latino New Orleans

Hispanic and

Latino

NEW ORLEANS

IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY SINCE THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

ANDREW SLUYTER

CASE WATKINS

JAMES P. CHANEY

ANNIE M. GIBSON

Foreword by Daniel D. Arreola

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

BATON ROUGE

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2015 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

LSU Press Paperback Original

First printing

DESIGNER: Michelle A. Neustrom

TYPEFACE: Sina Nova

All maps and other figures not otherwise credited were created by Andrew Sluyter and Case Watkins.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Sluyter, Andrew, 1958

Hispanic and Latino New Orleans : immigration and identity since the eighteenth century / Andrew Sluyter, Case Watkins, James P. Chaney, and Annie M. Gibson ; foreword by Daniel D. Arreola.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8071-6087-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8071-6089-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8071-6090-9 (epub) ISBN 978-0-8071-6091-6 (mobi) 1. Hispanic AmericansLouisianaNew OrleansHistory. 2. Hispanic AmericansEthnic identityHistory. 3. Latin AmericansLouisianaNew OrleansHistory. 4. ImmigrantsLouisianaNew Orleans. 5. New Orleans (La.) Emigration and immigrationHistory. 6. Latin AmericaEmigration and immigrationHistory. I. Watkins, Case, 1976 II. Chaney, James P., 1977 III. Gibson, Annie McNeill. IV. Title.

F379.N59S758 2015

305.9'06912076335dc23

2015020503

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

We dedicate this book to our families:

Carina Giusti de Sluyter and Sophia and Nicole Sluyter

Kristin N. Wylie

Hulet and Joyce Chaney

Gail, McNeill, and Joshua Gibson

CONTENTS

, by Daniel D. Arreola

FIGURES AND TABLES

FIGURES

TABLES

FOREWORD

IN HIS HIGHLY ACCLAIMED 1976 BOOK New Orleans: The Making of an Urban Landscape, geographer Peirce F. Lewis concluded a short discussion about the Crescent Citys Latin American influence by noting, In sum, New Orleans found its Latin connection an agreeable one, both profitable and colorful. And in their turn, it is said, Latin Americans enjoy New Orleans, if for no other reason than the Spanish appearance of the Vieux Carr, which they find familiar and comfortable (p. 51). During the 1970s, New Orleans was a city of few people with Latino-Hispanic ancestryperhaps 30,000 depending on who was counted and how counts were made, yet likely representing less than 4 percent of all residents. Latino New Orleans then comprised a series of small and scattered neighborhoods created over many generations and populated chiefly by more affluent and bilingual assimilated residents from only a few Latin Americanancestry groups.

Almost four decades later, New Orleanss Latino population has more than doubled. Today, the diversity of Hispanic-ancestry residents has been enhanced with immigrants from many parts of Latin America, and these new Latinos reside in many different quarters across the city. Hispanic and Latino New Orleans: Immigration and Identity since the Eighteenth Century, by Andrew Sluyter, Case Watkins, James P. Chaney, and Annie M. Gibson, chronicles the fascinating evolution of Latino populations in this often-proclaimed most distinctive of all American cities. The story moves from a broad, contextualizing introduction that compares New Orleans Hispanics to Latinos in other American cities through specific chapters that unveil the creation of the oldest and newest Hispanic and Latino communities in the Crescent City. The narrative is organized chronologically by time periods, from colonial to nineteenth century to twentieth and twenty first centuries. Through this temporal framing, the authors demonstrate how different circumstances have shaped the influence of Hispanic and Latino groups at different times.

The work is grounded in historic and contemporary accounts and statistical measurements from censuses, city directories, and ship manifests and supplemented with interviews of local residents to give an active voice to the story. A major strength is the effective way the authors contextualize each Latino population group. For example, we learn how the urban geographies of Cubans and Hondurans in New Orleans are infused with a lived past that connects them to ancestries in Cuba and Honduras. This enriches our understanding, developing a historical context that sheds light on how Cubans and Hondurans came to the Crescent City, and how connections to homeland economies in the past and the present shape the cultural geographies of those who now reside there. Detailed maps enhance the human geographies and enable comparison of the various groups and their residential locations at different time periods. The authors are especially adept at explaining how those geographies change through time as population groups develop tenure and economic viability in the evolving city.

This study will be significant to many fields that study Hispanic and Latino communities in the United States. Its many findings make it one of the most informed analyses of Hispanic and Latino populations for any city in the country. Its comprehensive framework informs how Hispanic and Latino cultures have inhabited and made their places in the Crescent City, and its presentation will prove a model for those who might develop similar studies of these cultures in other American cities where a diversity of Hispanic and Latino populations has emerged in the last several decades.

Daniel D. Arreola

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

WE OWE AN ENORMOUS DEBT TO many New Orleans Hispanics and Latinos, so many of whom welcomed us into their homes and opened up their personal lives in order to share their experiences, opinions, and dreams concerning New Orleans. We hope the publication of this book repays them by widely sharing what they taught us. Specific individuals who helped with the project and do not wish to remain anonymous include the following, although the views expressed and conclusions reached remain our own: Martn Guterrez, Romualdo Romi Gonzlez, Alexey Mart Soltero, Javier Olondo, Aurelio Gonzlez, Sr., Leticia Gonzlez, Aurelio Gonzlez, Jr., Javier Olondo, Natalia Aristizbal Uribe and family, Pedro Piki Mendizbal, Anna Frachou, Rafael Delgadillo, Alexis Martnez, Eliza Llewellyn, Angie Ivette Becerril Delgado, Pablo Reyes, Roger Velsquez, Cristobal Maldonado, Robert M. Landry, Ana L. Menes, and Ueliton Barbosa Teixeira.

Librarians and archivists of many institutions assisted in recovering the Hispanic and Latino pasts of New Orleans. We especially thank those of the Louisiana State University Libraries, New Orleans Notarial Archive, New Orleans Public Library, Louisiana State Archives, Louisiana State Land Office, University of New Orleans Libraries, and Tulane University Libraries.

We also thank the funding agencies that made this project possible. The Louisiana Board of Regents and LSU Graduate School provided an Economic Development Assistantship grant for 200913 that funded much work on this project. In addition, the LSU College of Humanities and Social Sciences awarded Andrew Sluyter a Manship Summer Grant in 2014 to finalize the manuscript.