Acknowledgments

With enormous thanks and much love to:

Bob Weil, maestro and shepherd, without whom this book would not exist.

Steve Almond, who gave these pages more dedication than I had a right to ask.

Nick Giraldi, uncle, pal, pursuer of speed.

Will Menaker, tireless mind of many insights.

Bill Pierce, who listened without complaint.

Katie, Parma, Ethan, Aiden: my heroes.

David Patterson, steadfast 007.

Steve Attardo, graphic artist extraordinaire.

The committed staff at Norton/Liveright, paragon of publishing.

The editors of Kenyon Review, Antioch Review, The Pushcart Prize 2010, and Best American Magazine Writing 2011, where sections of this memoir first appeared.

About the Author

William Giraldi grew up in Manville, New Jersey, and attended college at Drew University and Boston University. He is author of the novels Busy Monsters and Hold the Dark, fiction editor for the journal AGNI at Boston University, and a contributing editor at The New Republic. Hes been granted fellowships from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in The Oxford American, The New York Times, The Sun, Virginia Quarterly Review, The Baffler, Ploughshares, The Wall Street Journal, The New Criterion, and online at The Daily Beast and Salon. He lives in Boston with his wife and sons.

THE HEROS BODY

BOOK I

Youth ends when we perceive that no one wants our gay abandon. And the end may come in two ways: the realization that other people dislike it, or that we ourselves cannot continue with it. Weak men grow older in the first way, strong men in the second.

Cesare Pavese

BOOK II

We die with the dying:

See, they depart, and we go with them.

We are born with the dead:

See, they return, and bring us with them.

T. S. Eliot

The Heros Body is a work of nonfiction, but many of the names have been changed and certain identifying characteristics of individuals altered. The gym at which some of the action of this work takes place is unrelated to existing entities of the same name.

I

Eight months after meningitis, in the late spring of 1990, recently heart-thrashed by my first girlfriend, scrapped for a football star, weighing barely a buck and a quarter, spattered with acne, both earlobes aglitter with silver studs and my hairdo a mullet like a lemurs tail, and here is what happened to me:

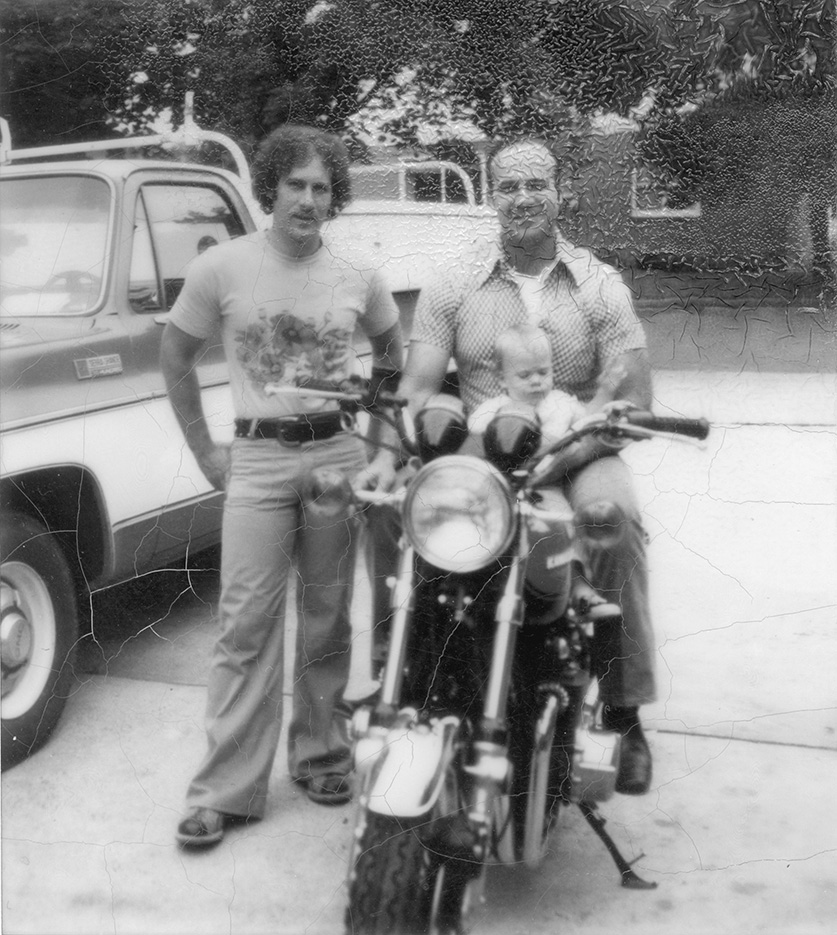

In the deadening heat of a May afternoon, stultified by sadness and boredom, I wandered over to my uncle Tonys house and found him weightlifting in the pro-grade gym hed installed in one half of his cobwebbed basement, AC/DC yawping from a set of speakers. The song? Problem Child. Tony lived across the street from my grandparents, where my father, siblings, and I ate dinner each weeknight, and so Id known about his gymhed built and welded most of it himselfbut never had a reason to care about it. Earnestly unjockish, Id long considered myself the artistic sort. I kept a notebook full of dismal poems, song lyrics, quotes from writers I wanted to remember. My hero was the reptilian rock god Axl Rose. Filthy and skinny, he looked hepatitic and I thought I should too.

But there in my uncles basement, my sallow non-physique mocking me from a wall of cracked mirrors, I clutched onto one of the smaller barbells and strained through a round of bicep curls, aping my uncle, who for whatever reason did not laugh or chase me away. And with that barbell in my grip, with blood surging through my slender arms, entire precincts inside me popped to life. Engorged veins pressed against the skin of my tiny biceps, and I rolled up the sleeves of my T-shirt to see them better, to watch their pulsing in the mirror.

Wordlessly I did what my uncle did, trailed him from the barbells to the dumbbells to the pulley machine, trying to keep up, mouthing along to the boisterous lyrics. And in the thirty minutes I spent down there that first day, I had sensations of baptism or birth. Those were thirty minutes during which Id forgotten to feel even a shard of pity for myself. I didnt know if I was lifting weights the right way, but I knew that I had just been claimed by something holy. Id return to his basement the following day, and the day after that. Id return every weekday for two years.

I see it clearly now: I was prompted by more than a need to stave off my melancholy, prompted by forces I couldnt have anticipated or explained. There was the obvious motive, a desperation to alter my twiggy physique, transform it into a monument worthy of my ex-girlfriends lust, a kind of revenge so important to shafted teenage boys. The footballer for whom shed ditched me? Just two weeks before I wandered down into my uncles basement, hed rammed me against a classroom door, said for me to meet him outside, so I can teach you a lesson, and I was too shaken to ask him what lesson that might be, since he was the thieving scoundrel between us. Of course I didnt meet him outside; hed have ruined me in a fistfight. He and his pals called me exactly what youd expect them to call me: pussy, sissy, faggot.

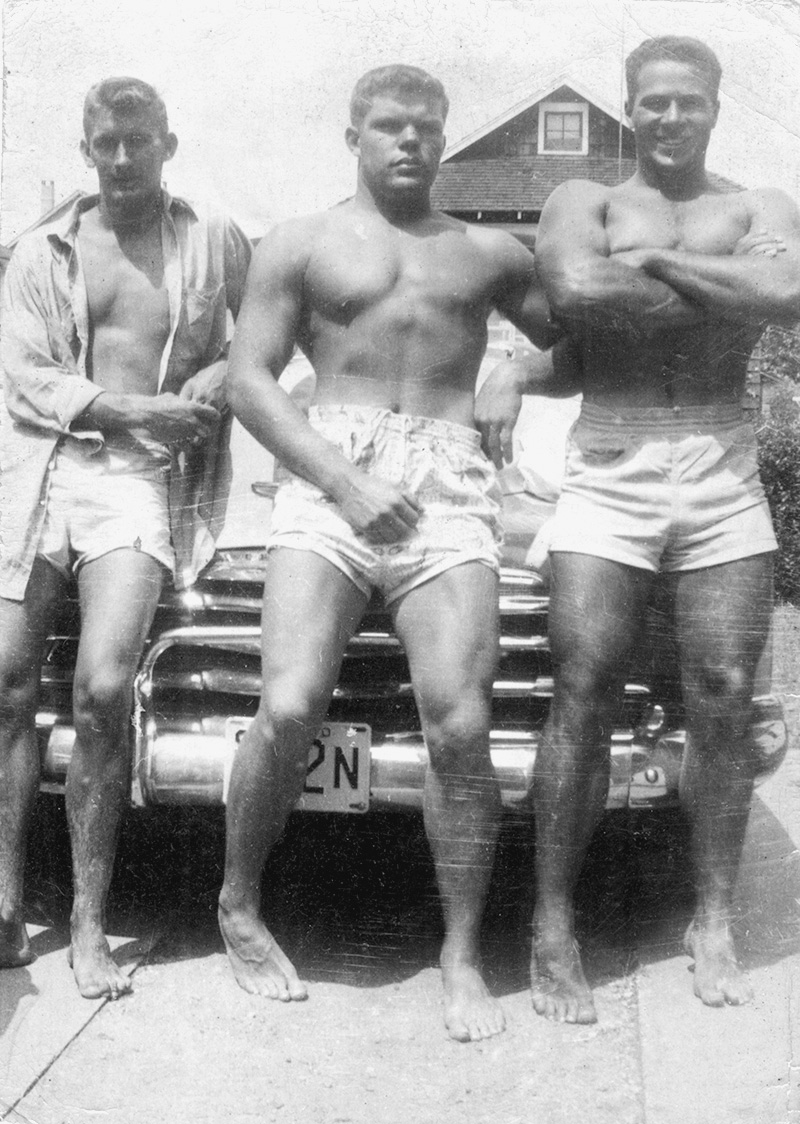

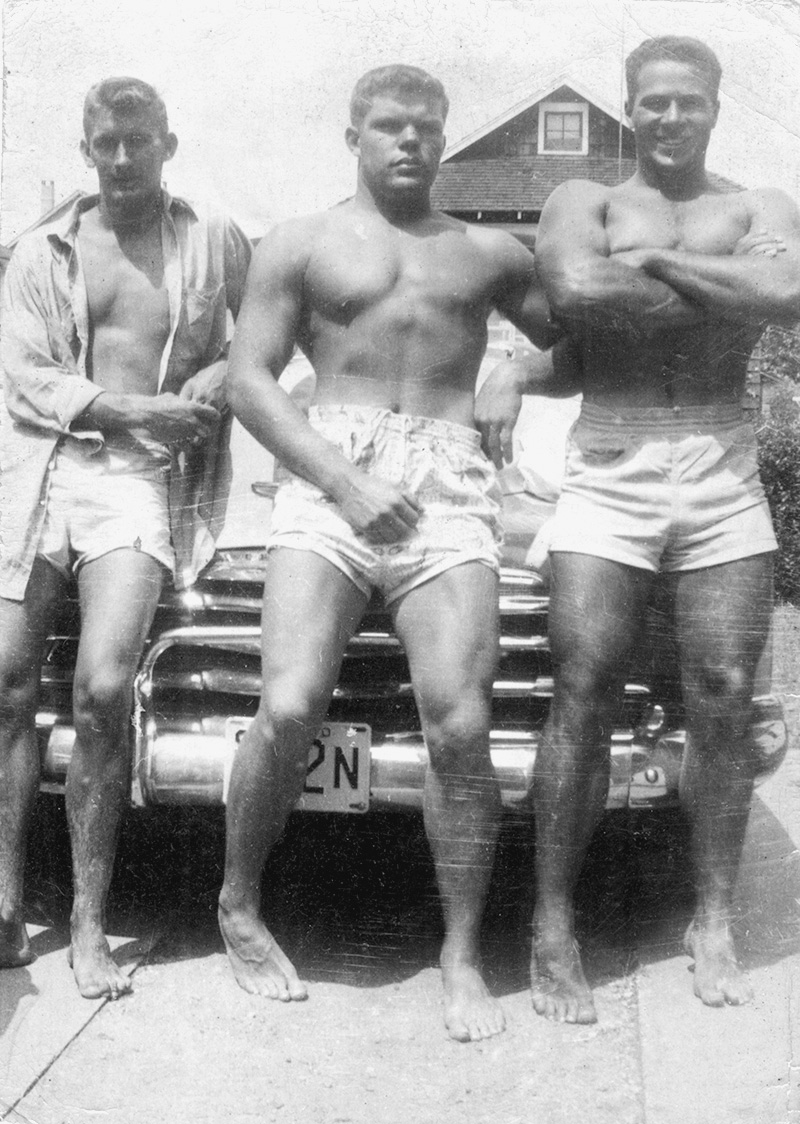

There was also the chronic memory of that month-long meningitis, the successful shame of my bodys failing, the need to fortress myself with muscle in order to spare my father the high cost of my weakness, to preempt whatever disease might choose me next. But the mightiest motive, the one not entirely apparent to me? To obtain the acceptance of my father and uncles and the imperious grandfather we called Popto forge a spot for myself in this family of unapologetic, unforgiving masculinity.

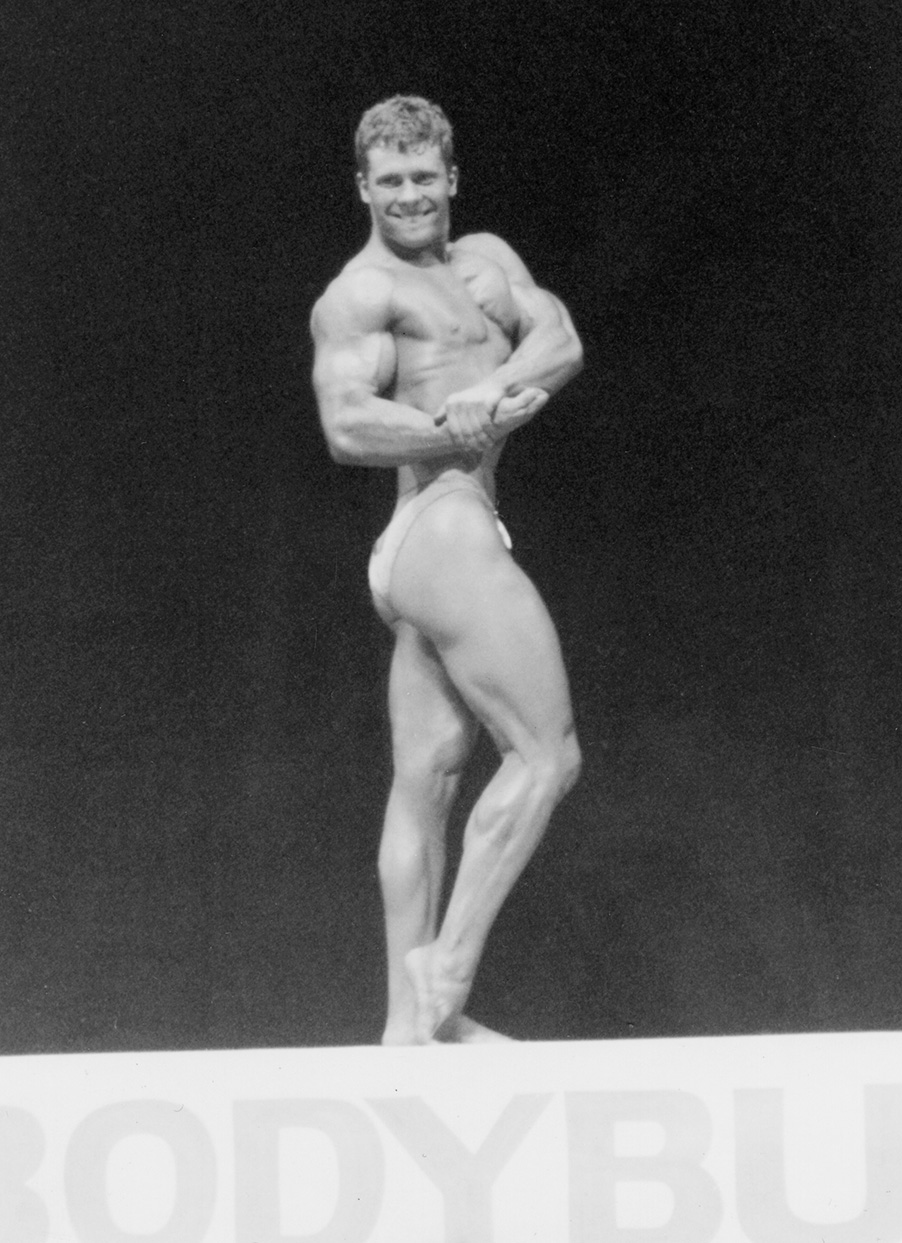

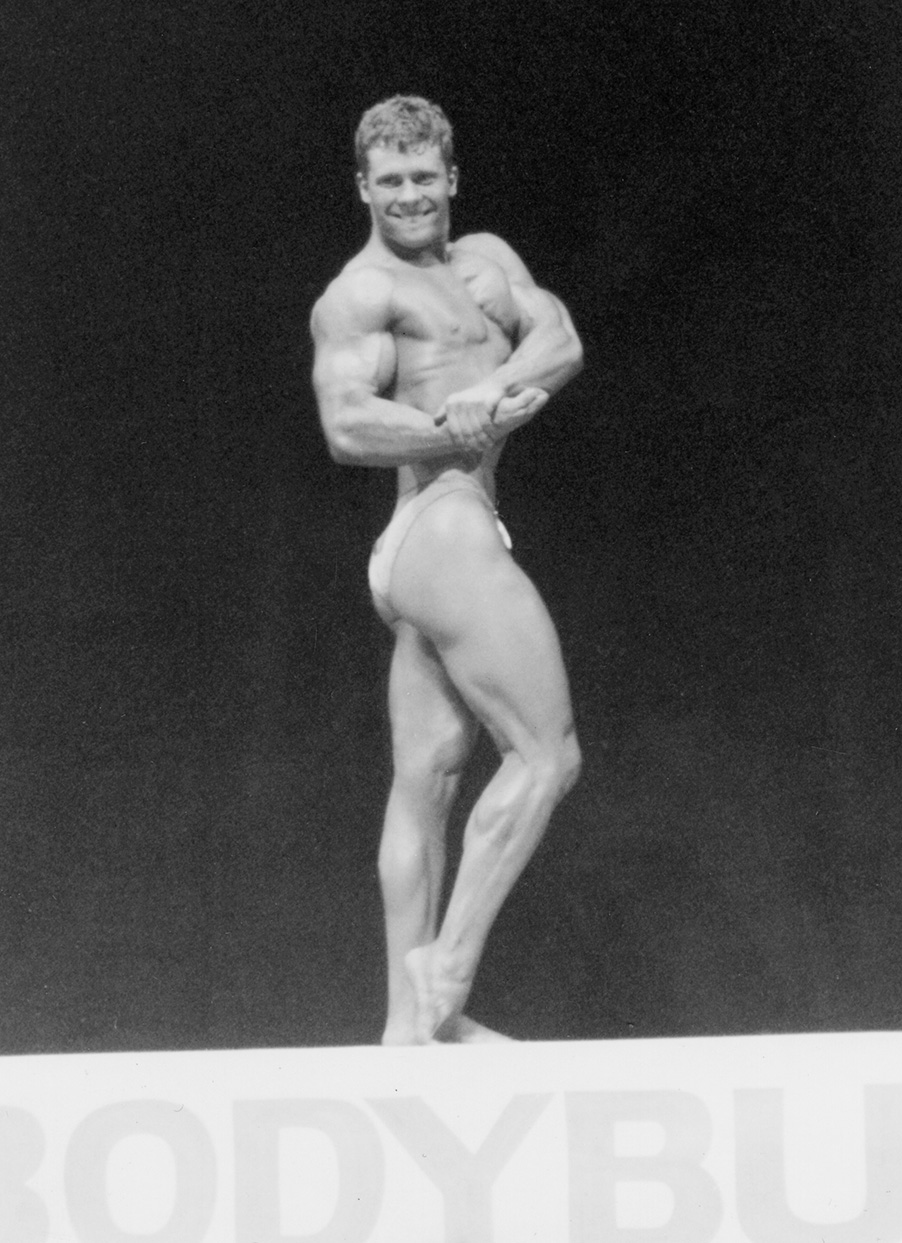

Before we return to that basement and those weights, there are certain essential details you need to know about where and how I was raised, details that will help explain how bodybuilding was for me both impossible and inevitable, and how it developed into an obsession that included brutalizing workouts, anabolic steroids, competitions, an absolute revamping of the self.

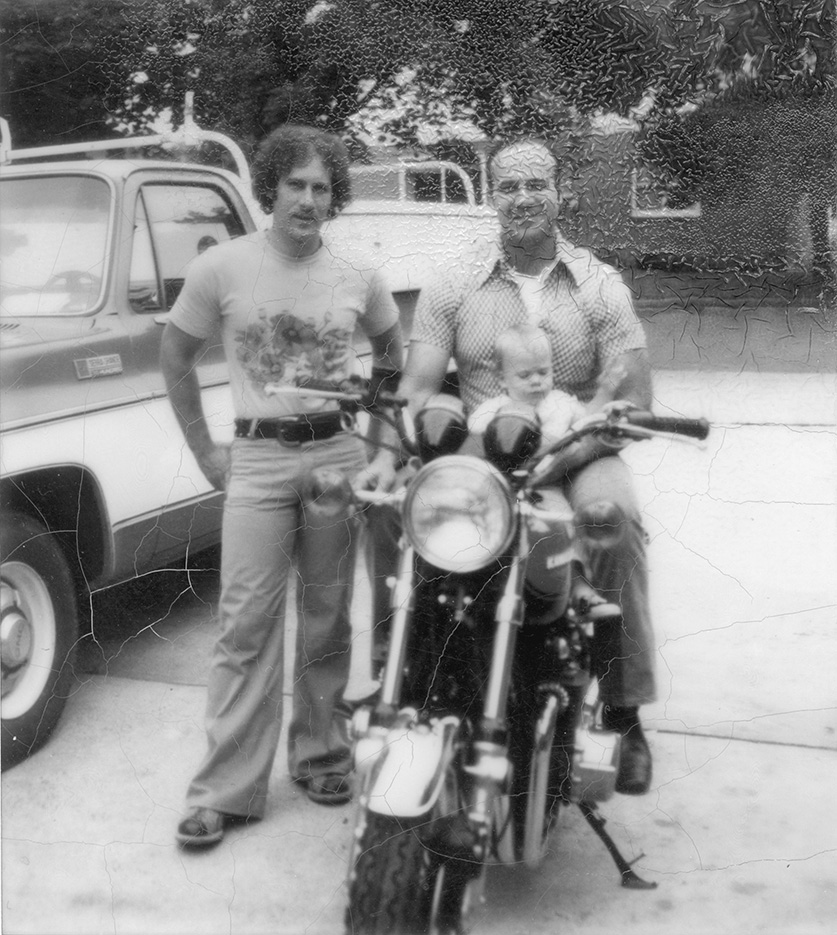

My hometowns name, Manville, lets you know precisely what youre getting: pure Jersey. A town of plumbers and masons, pickup trucks and motorcycles, bars, liquor stores, and football fields, diners, churches, and auto repair shops, and a notorious, all-nude strip club once called Franks Chicken House. Go to central Jersey, ask any working-class guy over thirty about Franks Chicken House, and hell point the way: the town of Manville, right off Route 206, fifteen minutes from the sylvan spread of Princeton, a town straight from the blue notes of a Springsteen song.

Manville was no Princeton. A meager two and a half square miles of low-lying land, the town is bordered by the Raritan River at the north and east. Roughly once a decade, it gets swallowed by an end-times flood. It was named for the Johns-Manville Corporation, which produced asbestos building materials that ravaged the lungs of its many workers. The manufacturing plant, defunct by the time I was a child, sat on Main Street, blocks-long behind rusted fences, vacant but for the spirits of the dead flitting through those empty spaces in search of better air to breathe.

Next page