for Nancy

Hope cannot be said to exist, nor can it be said not to exist. It is just like roads across the earth. For actually the earth has no roads to begin with but when many people pass one way, a road is made.

Lu Xun, My Old Home, 1921

Contents

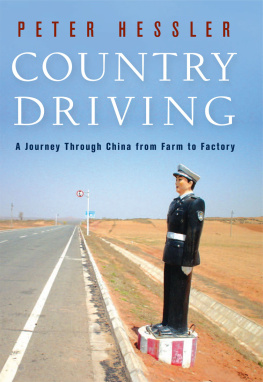

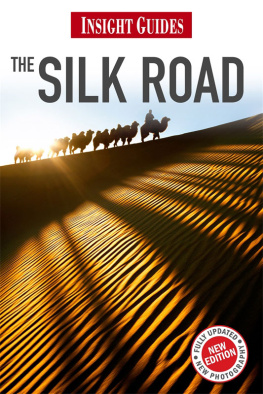

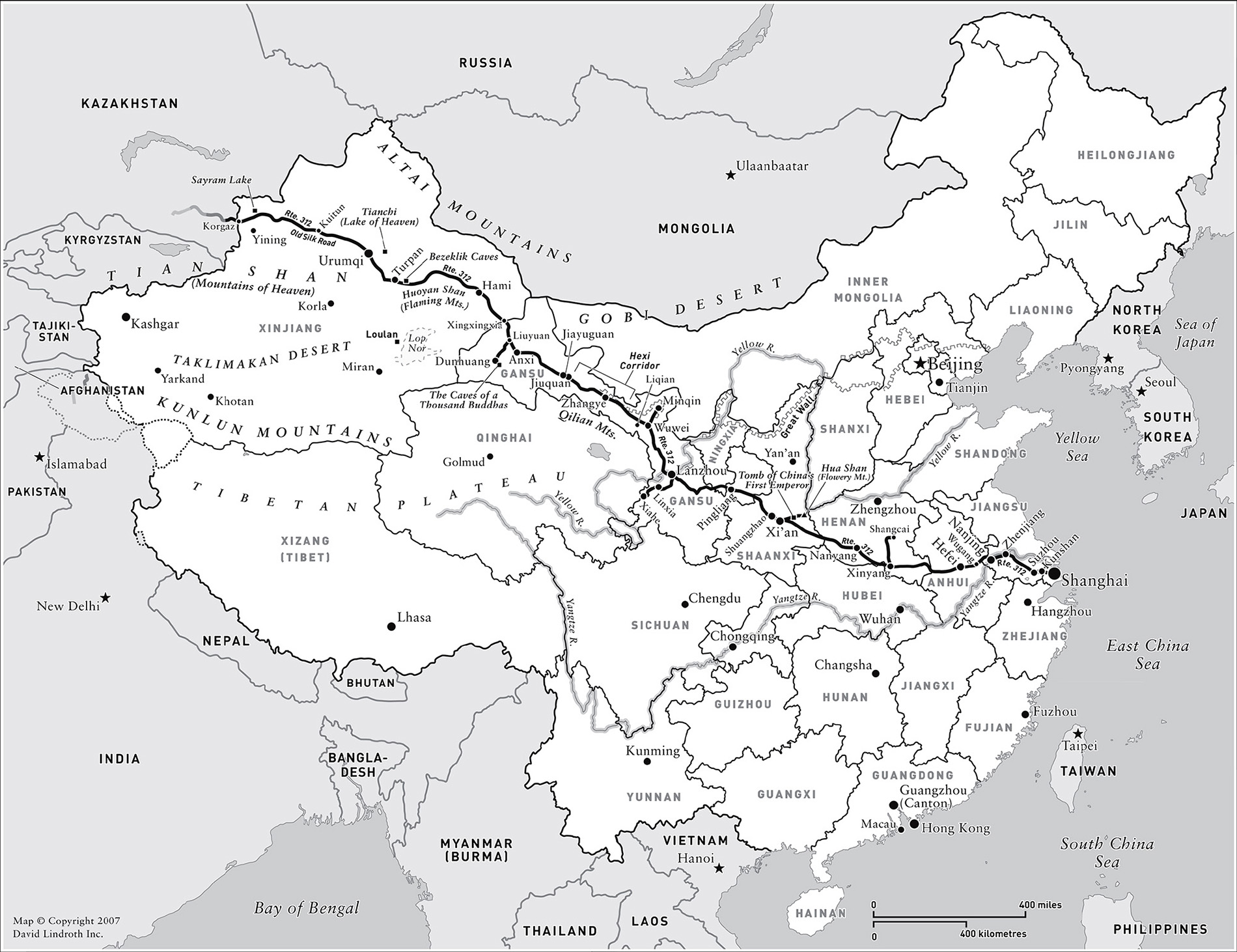

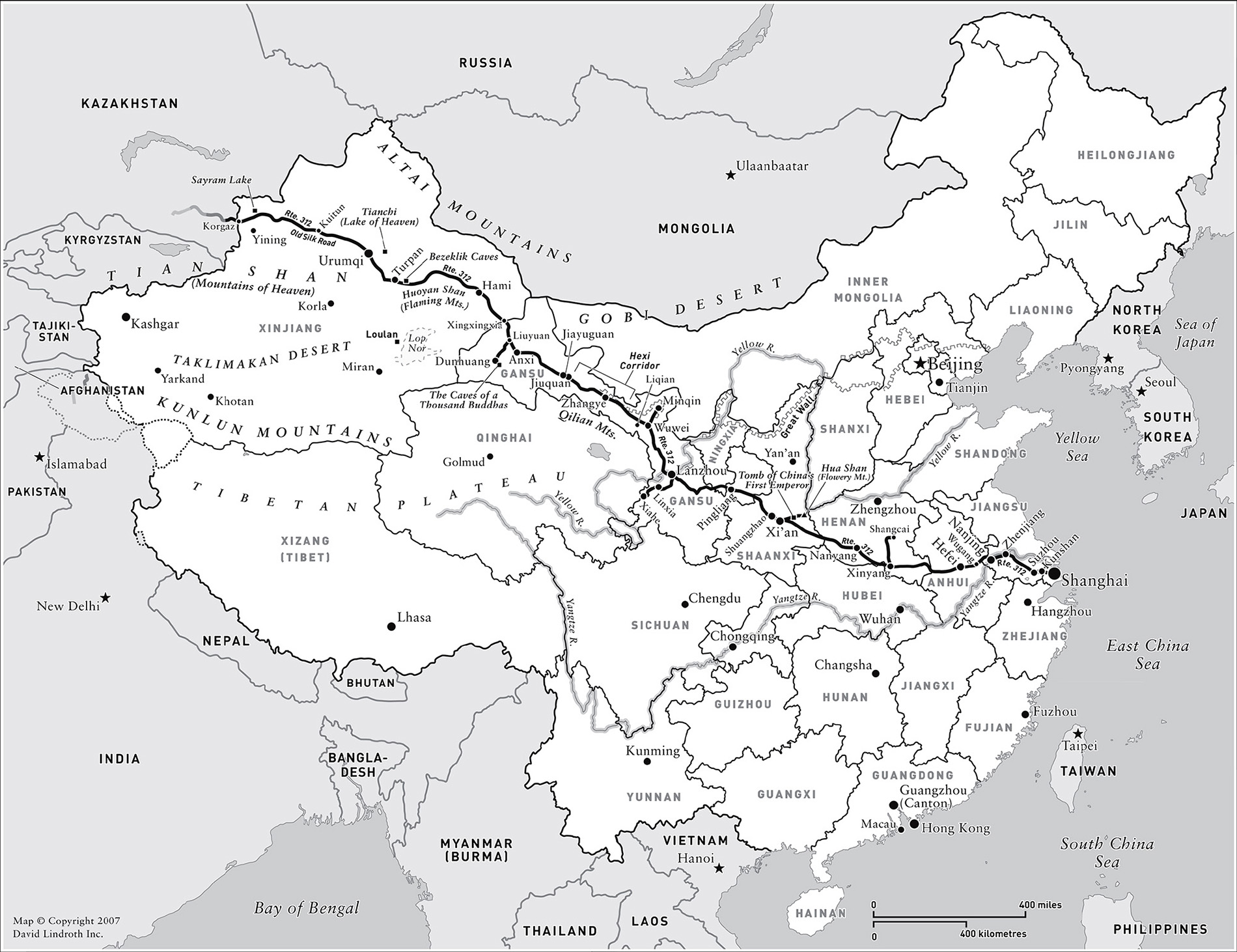

The worn black road shoots like an arrow across the desert until it thuds into a low escarpment of rocks, which rises from the lunar landscape of the Gobis yellow scrubland. The craggy boulders form a ravine that soon encloses the road as it bends for the first time in a hundred miles, then dumps the traveller in a small town that had not been visible from the highway. The ravine gives the town its name, Xingxingxia, which in English means Starry Gorge.

Starry Gorge is a two-horse town, with just a few hundred residents. It caters to the truckers, the long-distance buses and the occasional crazy traveller who chooses to cross the Gobi Desert by road. The town owes its existence to a small freshwater well, the only one for miles around, which has sustained man and beast for centuries on their journeys along this merciless section of the ancient Silk Road. Xingxingxia (pronounced shing-shing-shyah) marks the travellers entry into what used to be called Turkestan but is now the Chinese region of Xinjiang. The gorge to the east and a large tollgate to the west provide the bookends for this shabby jumble of truck stops, houses and one large petrol station that poke out of the scorched desert earth and up into the clear blue Central Asian sky. The hostile sun is high, almost melting the tarmac, and Im standing beside the road, trying to hitch a ride.

This is not just any old road. This is Chinas Mother Road, and its name is Route 312. Ive been journeying by bus, truck and taxi all the way from the roads beginning in Shanghai nearly 2,000 miles east of here. At the ancient city of Xian, it picked up the route of the old Silk Road, which in ancient times ran through the Gobi Desert, through Starry Gorge, to Central Asia, and westward to Persia and Europe. Im about two-thirds of the way along my 3,000-mile journey, with a 1,000 miles left to ride to the roads end, at the Chinese border with Kazakhstan.

I am unshaven and burned by the fierce desert sun, weary but exhilarated after six weeks travelling, and weary but still exhilarated after six years of living in China as a journalist. This is my final journey across the country before I leave and move to Europe.

A group of truck drivers has gathered to chat at the petrol station. I wander over to see if any of them will give me a ride west. Word has reached them that, just ahead on Route 312, a patrol car from the small Starry Gorge police station is sitting, waiting. They are all overloaded and will be fined if they are stopped. We stand and make small talk for ten minutes. Most of them are cautious about giving a ride to a westerner. Finally, word comes through that the police car has gone, and the group disperses, each driver to his own truck. Im left standing until one of them looks back at me and, with a short jerk of his head, motions me towards his truck. I follow, and jump into the cab. He fires up the engine, rolls the big blue beast on to the road and out into the hungry, golden Gobi.

Where have you come from? I ask him.

Shanghai.

And where are you heading?

Urumqi.

Whats that huge thing on the back of your truck?

Its an industrial filter, going to a company in Urumqi. And last week I was driving from Urumqi to Shanghai, with a truck full of melons.

Its a symbolic exchange, fresh produce flows east for the consumers of Chinas coastal cities. Industrial equipment flows west to help with the construction of the less developed regions inland.

Urumqi (pronounced oo-room-chee) is the capital of Xinjiang, the heart of Central Asia, and the city furthest from an ocean in the world.

The drivers name is Liu Qiang (pronounced leo chang). He travels back and forth along Route 312 from Xinjiang to Shanghai all through the year, driving alternately day and night with his buddy, Wang, who is asleep on the narrow bunk behind our seats. All the trucks have two drivers, so that they can travel twenty-four hours a day, stopping only when they need to use the rest stops along the 3,000-mile road.

Hows life as a trucker these day? I ask him. Can you make money?

Tai nan le. Its difficult, he laments, lighting up the first of many cigarettes and tossing his lighter on to the dashboard. We have to overload our trucks to make any money, but the police lie in wait and fine us.

He chain-smokes as he drives and talks with a rat-a-tat staccato.

I get paid 18,000 yuan [about $2,200] to take a load from Urumqi to Shanghai or back again. I have to pay out about 15,000 yuan in tolls, costs and fines to the policemen. So from a one-week trip, I earn about 3,000 yuan [roughly $380].

Thats not a bad income, I say. Many Chinese do not earn that in a month.

Yes, but theres wear and tear on my truck, and wear and tear on me. And Im getting paid less as competition increases. Plus the fact that police fines are going up.

I cannot think of a better travelling companion. Liu is that wonderful mix of modesty and bravado that characterises many Chinese men. Hes built like a boxer, short and muscular, and although he left school at sixteen, he is a one-man philosophy department, with an opinion on everything. One minute he is lamenting the moral decline of China, the next he is telling me about the roadside brothels he visits along the way. He is a coiled spring of energy, with laughter and fury exploding in equal measures. Laughter just at life itself, in all its modern Chinese craziness. Fury mostly at corrupt Communist Party officials and policemen. Like so many modern Chinese people, he is torn between a deep love of his country and a deep anger at the people who govern it.

We travel for hours across the relentless Gobi, talking intensely at first but then with long periods of silence, during which he just drives, and I just sit, and Wang just snores in the bunk behind. The raw beauty of the desert the implacable desert whose vicious sandstorms used to consume whole caravans of camels and their precious cargoes, the unquenchable desert that used to resist all but the most hardy travellers rolls past outside.

Though still wild, it is slowly being conquered by an army of blue Chinese-made East Wind trucks. As roads such as Route 312 grow busier, and distant cities such as Urumqi are brought closer to the main centres of population further east, the desert seems a little less dangerous now. An occasional truck whooshes past in the opposite direction, shaking us with its slipstream. Passenger buses rush past too, and occasional cars, but not many.

Liu Qiang talks of the development he sees every day, the transformation of a country changed by the loosening of government controls, by the influx of foreign money, and most of all by the movement of people, untethered from their communist past. But mobility and greater freedom have changed peoples characters, he says, and not always for the better.

In the past, everyone was poor, says Liu, but everyone was honest. Now, everyone is more free, but there is luan, there is chaos. Money has made everyone go bad. He uses the Chinese phrase, a hundred times more illustrative than its canine English equivalent. Ren chi ren, he says. Its man eat man now.

This is a book about people such as Liu Qiang. Ordinary Chinese people caught up in an extraordinary moment in time. China in the early twenty-first century is, above all things, a nation on the move, as millions of rural people leave their villages and head to the cities, looking for work. Many still travel by rail, but increasingly people are travelling by road. Exact numbers are difficult to gauge, but most experts estimate that 150 million (possibly as many as 200 million) people have left their home villages in search of work in cities around China. It is the largest migration in human history.

Next page