CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

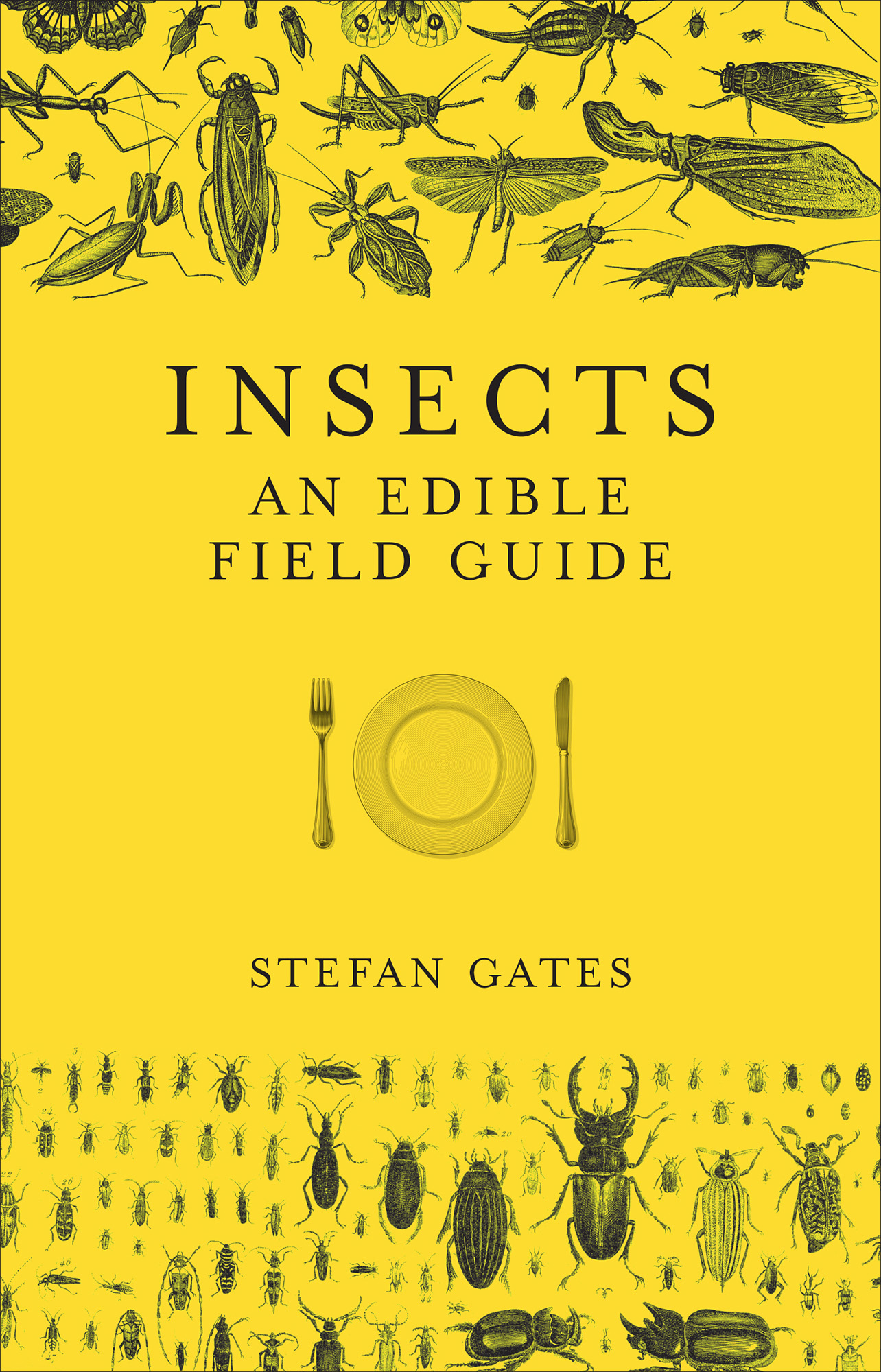

Happy though I am to take all the credit for this book, I must grudgingly admit to the tiniest bit of help from dozens of brilliant entomologists, anthropologists, climate-change scientists, naturalists, statisticians, cooks and food writers whose work, both current and historical, I consulted, tickled and plundered. Special mention must go the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation for its publications and sheer enthusiasm, and also to the late Gene DeFoliart (whose extraordinary online bibliography is something of a gateway drug into entomophagy).

Particularly sumptuous acknowledgements are due to several people: the wonderful Hugh Woodward, whose efforts are reflected not just in the depth of information herein, but in some very fine turns of phrase, and for keeping me sane when I should, by rights, have gone stark raving locust. My entomologist friend Sally-Ann Spence kept the book in check and on track, and let me fiddle with Darwins specimens at the Pitt-Rivers in Oxford. A huge thank-you to the fantastic Jessica Barnfield for suggesting this book and for editing it so well despite being a vegetarian. And a big thank you to Candela Riveros for her wonderful illustrations.

Many people are to blame for leading me on the path to entomophagic enlightenment, especially Daisy and Poppy (for the day they licked their fingers, dipped them into a jar of bug eggs and pronounced them delicious), Georgia Glynn Smith (who, lets be honest, struggles to love insects), Kari Lia, Nik Porter, Nipaporn Jam Potong, Mark Collins, Will Daws, Karen OConnor, Richard Klein, Clare Paterson, Cassian Harrison, Janice Hadlow, Jan Croxson, Borra Garson, the crazy tarantula boys of Cambodia, Brodie Thompson and Eliza Hazlewood.

Thanks to my beloved BBC and the great British public for funding them for sharing so many of my fascinations and obsessions.

And finally, thanks to all the ants, bugs, locusts, grubs, worms, spiders, gastropods and myriapods Ive met on the way to writing this book. Sorry for eating you. But lets face it, if I didnt, something else would.

UK AND NORTHERN EUROPE

You might think that the entomophagy-minded foodie would find slim pickings in northern Europe. After all, the region is colder than most, whereas insects thrive in warm climates. This can make insect-foraging a calorie-neutral or even calorie-negative endeavour, (whereby more energy is spent collecting your dinner than you gain from eating it). Much like munching on celery. And, yes, in terms of sheer number of species Europe ranks last in the league table of edible insects, with only 2% of the worlds commonly eaten species.

But there are two counter-arguments to offer sceptics.

1. Insects are tenacious little critters and are found everywhere, especially in summer, as long as you know where to look and what to look for (and you have this book to hand). Its usually possible to walk into any garden that isnt under a blanket of snow and find a mouthful of protein.

2. The future of the world. Europe has always been at the forefront of global culinary endeavour, largely due to the work of the Dutch, who have been extracting food from an unpromising patch of mud since at least the Reformation. And with some degree of inevitability, they have thrown their weight behind entomophagy as an important solution to the worlds food problems.

The Dutch are farming organic mealworms and crickets for human consumption, and the good folk at Wageningen University produce some brilliant entomophagy research. Big ideas that change global nutrition often sound a bit odd and distasteful at first. That doesnt mean we shouldnt try to change the world by changing what we eat.

THE MOST SURPRISING INSECT-BASED DISHES

Some of the most exciting developments in entomophagy have come from the most surprising places. Despite a climate that doesnt naturally lend itself to cold-blooded animals, northern Europe has developed a pleasing proportion of the worlds oddest insect dishes. Check off the ones youve tried.

1. Bee mayonnaise , Denmark.

2. Cockchafer soup , France.

3. Fly burgers , Malawi/Tanzania.

4. Mealworm ice cream , San Francisco, USA.

5. Christmas minced flies , London, UK.

(Admittedly, that last entry was one of your authors.)

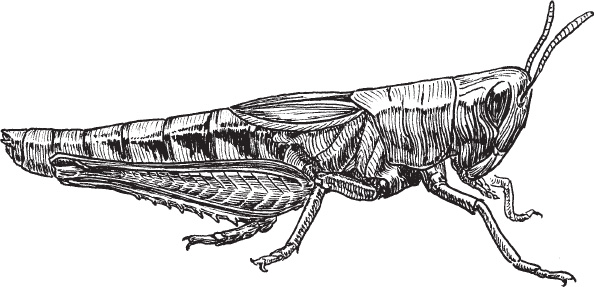

MEADOW GRASSHOPPER

Chorthippus parallelus

The meadow grasshopper is known for its call; it attracts attention by rubbing its legs together and adding a scratchy noise to the general cacophony of a field on a summers evening. The grasshopper is particularly good at hopping because its strong back legs act as tiny catapults it bends its legs at the knee so that a spring-like mechanism stores up energy, then, when the grasshopper is ready to jump, it relaxes the leg muscles, allowing the spring to release and flinging it stylishly into the air. Despite this, they are very easy to catch when out in the open or on short grass, but in the middle of fields they invariably disappear into the vegetation, never to be seen again.

Taste: When freshly cooked they are crunchy and nutty with a strong umami hit.

Country: Found throughout the UK and much of Europe.

Habitat: In the wild the meadow grasshopper lives in damp pastures and meadows, spending its time merrily chirruping and feeding on leaves.

Dangers: They have no sting or venom and are no threat to humans.

How to cook/prep: Best roasted or deep-fried.

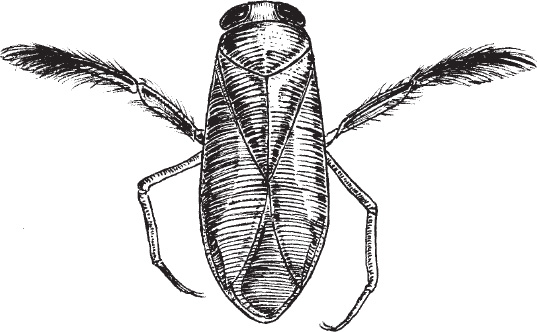

WATER BOATMAN

Corixidae

The water boatman spends its days leisurely rowing across ponds with its oar-like legs, eating algae and bits of vegetable detritus (which makes it unusual among its mostly carnivorous pond peers). But its most impressive skill is the ability to sing with its penis. Yes, you read that right: its a penis-singer. It achieves this by rubbing the penis against its abdomen. The volume is spectacularly high, ranking as the loudest creature relative to its size. It has no teeth and instead dissolves its chosen morsel with its saliva before sucking up the resulting mush using its straw-like mouth. To survive underwater it has developed the ingenious technique of bringing a tiny air bubble under with it, tucked under its wing cases like a primitive scuba diver. Backswimmers (a similar species) are popular in Thailand and are eaten in soups or salted to make a dish known as jom. Water boatmen are also eaten in Mexico, both the adults and their eggs.

Taste: The eggs are quite the delicacy in Mexico, where they are known as Mexican caviar. The adults on the other hand are slightly crablike.

Country: Widely spread throughout the UK.

Habitat: Happiest living their vegetarian existence in weedy ponds and rivers.

Dangers: Some species of backswimmer can bite, so do be careful.

How to cook/prep: Can be roasted, fried or boiled.

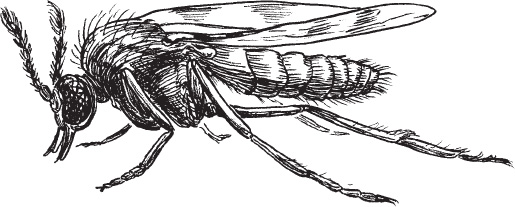

HIGHLAND MIDGES