Text copyright 2014 by Daniella Martin

All rights reserved.

No part of this work may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher.

Published by Amazon Publishing, Seattle

www.apub.com

Amazon, the Amazon logo and Amazon Publishing are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

eISBN: 9781477850664

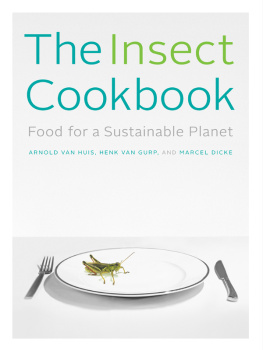

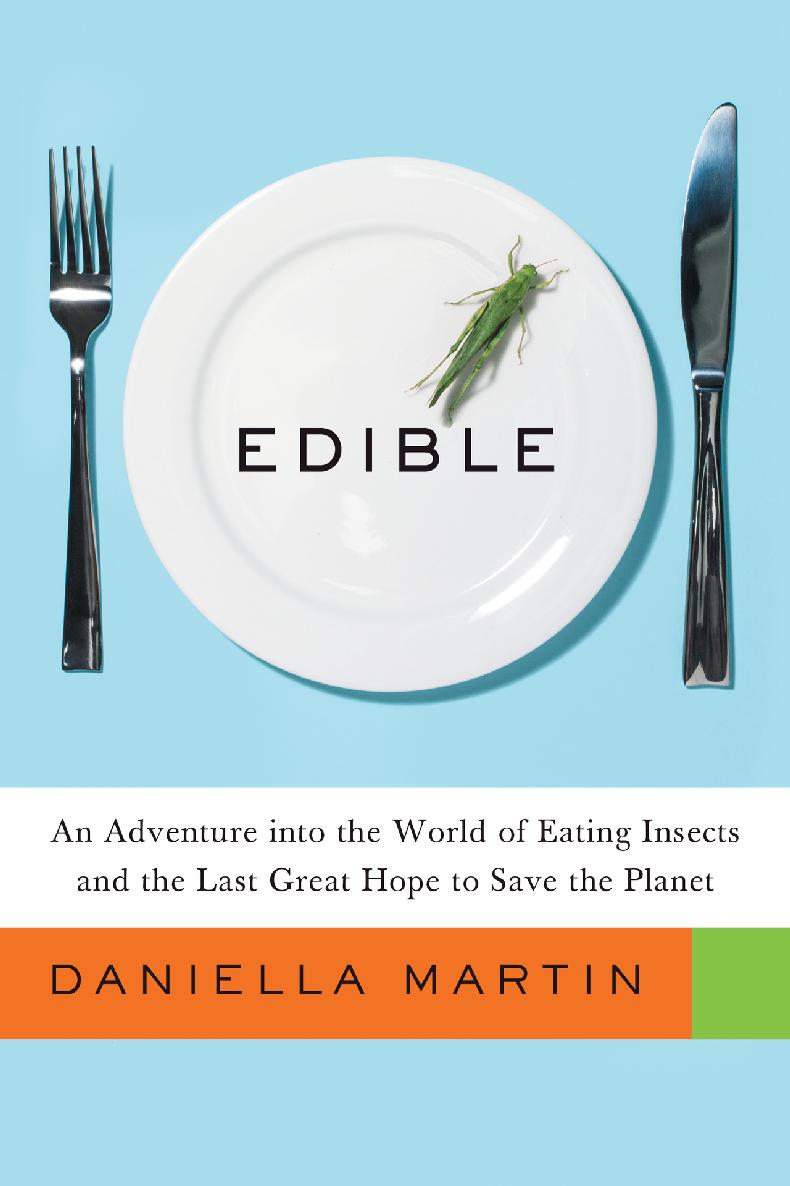

Cover designed by Rodrigo Corral Design

Author photograph by James Rollyson

For Brian, my smizmar

Contents

Introduction

T HIS BOOK IS about eating bugs. For real. And if you make it all the way through the book, youre going to want to taste the revolution for yourself.

Why? Eating bugs makes senseecological, nutritional, economic, global, and culinary sense. Yes, they even taste good. Many people disdainfully say they dont like bugs, are afraid of them, or are repelled by them on some deep, subconscious, yet stridently self-righteous level. But like them or not, insects are the largest terrestrial biomass on Earth. That means of all the animals that live on dry land, insects are most of them. If someone were to determine, by the numbers, what Earth was about, they would conclude: insects. Beetles, mostly.

Consider the fact that the planet you live on has more bugs on it than any other animal (I know, its making your skin crawl just thinking about it). Insects were here before us, and theyll help us decompose after we die. People say money makes the world go round, which may be true within human society, but in nature, its bugs. Bugs do the majority of the pollinating and decomposing, the real circle of life. And thats not to mention how important pollination is for the food we grow and eat. The bugs we love to hatelike bees, wasps, and even mosquitoesall contribute to pollination, which helps begin life. Decomposition, largely performed by insects, dismantles it, making room for more life to flourish. And yet we tend to treat them as a whole as if they are worse than the garbage certain species help decompose.

This is a large part of the reason I am so inspired by insects, why Ive spent nearly a decade thinking about them and studying them, and why I wrote this book. I truly believe we should all be eating bugsas our ancestors did, as our global neighbors do, as our primate cousins do, and as we ourselves do constantly, by accident, without realizing it.

Im not asking anyone to drastically change their diet, to give up foods they love, or to subscribe to some new overarching system. Im not even going to suggest substituting insects in place of other foods, per se. Im simply asking you to open your mindjust a littleto give bugs a chance and a place on your palate.

Whenever anyone finds out for the first time just what it is I do, the first thing they want to know is How did you get into that ?

The first time I ever ate a bug, on purpose, was in Oaxaca, Mexico. I was traveling on a student visa, studying pre-Columbian food and medicine for my BA in cultural anthropology. Mainly, I wanted to see what vestiges of early Mexican life had survived the Spanish conquistadors, and their systematic squelching of native practices, into modern-day life. Id read about entomophagyinsect eatingin college, how the ancient Aztecs and Maya ate everything that was available to them, including insects, rodents, and reptiles. If it moved, they ate it. And often to great successthere were stories about how, during the right season, a person could wade into Lake Tenochtitlan, the center of the Aztec world, with a couple of agave-fiber nets and come back with twenty to thirty pounds of larvae and other aquatic insects within a few hours. That might not sound so great to us, but when compared with the difficulties, dangers, and unreliability of hunting, its a pretty darn awesome return on investment. Thats a big load of high-quality protein, fats, minerals, and vitamins for remarkably little effort, energy, and risk.

I knew when I went to Mexico that I was definitely going to have to try edible insects for myself. It was also one of the few easily observable practices that was a clear holdover from earlier times. Certainly, there are many foods that remain as popular today in Mexico as they were when they were first cultivated and developed by the Aztecs: corn tortillas, tamales, beans, chiles. But the historic purity of many of these foods is somewhat diluted with modern ingredients, such as lard, and modern processing machines. Insects, however, are often eaten just as they were thousands of years ago: dried in the sun, toasted on a comal (a flat, earthenware cooking surface), or ground up in a molcajete , a mortar and pestle carved from volcanic rock, one of the worlds oldest kitchen tools. In the cities, insects are generally deemed a delicacy (and their price reflects this), but in the countryside, where the majority of native people live, they are more a way of life. For me, this lent them a certain wholeness as an unbroken tie to the pastand thus anthropologically interesting in terms of my goal of recording the modern life of ancient traditions.

When I saw a middle-aged woman, dressed in a brightly colored Mayan wrap, selling toasted grasshoppers in the Oaxaca city square, it was a no-brainer. I paid my 20 pesos and received a little paper bag of the brick-red bugs. I took my roasted grasshoppers, called chapulines , and sat down at a table in an outdoor caf. I was definitely going to need something to wash this down with. I ordered a Coke and poured the chapulines out onto the white tablecloth, intending to take a cool photograph before sampling them. Just as I was getting ready to brave my first bite of bug, the strangest thing happened: Kids from the street, likely of Trique indigenous descent, made a beeline for me and began eating the chapulines right off my tablewithout even asking! I hardly had time to grab a few for myself, as they gobbled them right up.

Now, Ive thought about this in the years since it happened: Yes, the kids were likely hungrymore than 70 percent of Oaxacans live in extreme poverty. These children spend their days begging tourists on the streets of the city while their parents sell various things in the market: elotes , a chili-spiced corn on the cob; indigenous crafts and trinkets; and, of course, toasted insects. The kids had probably seen lots of tourists buy a bag of chapulines for the experience, eat one or two, squinch up their faces, take a few photos, and throw the rest away. The kids must have supposed, Eh, she wont care, shes a tourist. Lets get em while the gettings good, while theyre still crispy and we dont have to fish them out of the trash. On the one hand, it could be interpreted as a bit Dickensian; on the other, Cheetos are technically made of yuckier stuff than this.

I managed to taste a few chapulines , and I probably would have thrown the rest away. They tasted unfamiliar, sort of like a shriveled, spicy, slightly burned potato chip, but mostly, the mind gets in the way, telling you it wont be safe or good to eat too many. Heck, you might turn into a bug yourself (Dickens meets Kafka?). But there are lots of foods I love that others are slightly grossed out by: beef tongue, smelly fermented soybeans, tinned sardines and oysters, oily raw mackerel, and all manner of fish eggs. So why not bugs?