The Insect Cookbook

ARTS AND TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Het Insectenkookboek 2012 by Arnold van Huis, Henk van Gurp, and Marcel Dicke. Originally published by Uitgeverij Atlas Contact, Amsterdam

English-language edition copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53621-9

This book was made possible through support from the DOEN Foundation, the Uyttenboogaart-Eliasen Foundation, Wageningen University, and the Dutch Foundation for Literature.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Huis, Arnold van.

[Insectenkookboek. English]

The Insect cookbook : food for a sustainable planet / Arnold van Huis, Henk van Gurp, and Marcel Dicke ; translated by Franoise Takken-Kaminker and Diane Blumenfeld-Schaap. English-language edition.

pages cm (Arts and traditions of the table : perspectives on culinary history)

Originally published by Uitgeverij Atlas Contact, Amsterdam in 2012 as Het Insectenkookboek.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16684-3 (cloth : acid-free paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-53621-9 (e-book)

1. Cooking (Insects) 2. Edible insects. I. Gurp, Henk van. II. Dicke, Marcel. III. Title.

TX746.H8513 2014

641.6'96dc23

2013030373

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

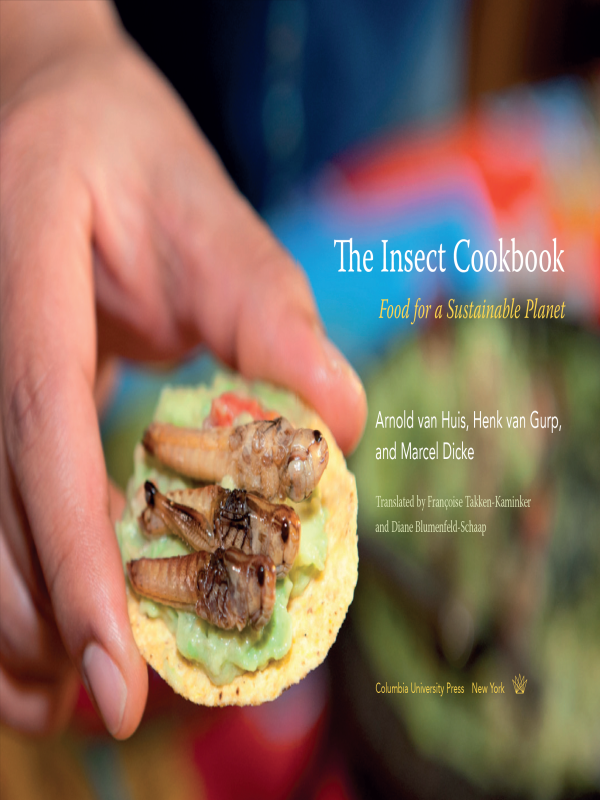

FRONTISPIECE: Tortilla with grasshoppers and guacamole. (Lotte Stekelenburg)

COVER IMAGES: Darlyne A. Murawski Getty and Cultura Limited / SuperStock

COVER DESIGN: Evan Gaffney

References to Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the authors nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

Migratory locust, reared in the Netherlands for culinary use. (Lotte Stekelenburg)

The first time I ate an insect was somewhere in Burundi, in the 1980s. I was accompanying a farmer on her walk through an area that had been forested in the past, where now there were only old, poorly tended oil palm trees dating from the Belgian colonial days. One of the palm trees had been knocked down in a storm the previous night. When the farmer noticed this felled tree, she ran to it enthusiastically. Her eager fingers searched within the leaf axils just underneath the trees crown, and she triumphantly pulled out a handful of fat white grubs. After wrapping the insects carefully in some leaves, she took them home and roasted them that same afternoon. I became curious at her evident delight in this find. And indeed, the small crispy treats were delicious! Shortly thereafter, I was offered honey-flavored, roasted grasshoppers in Syria and was by then convinced: insects not only are a good idea nutritionally, but also taste wonderful.

Taste, however, is only one important aspect to bear in mind. Of prime importance to me, as an agricultural specialist, is that insects can contribute to protein supplies worldwide. I see the production of animal protein to feed a growing world population as one of the major scientific and social challenges of our times. Animal protein (from meat, fish, dairy products, eggs) is essential for everyone, but especially so for children, pregnant women, and the vulnerable elderly. Although a healthy adult who eats a large variety of foods can, for a time, do without animal protein, the diet of most people isnt adequately balanced.

People everywhere in the world have a preference for animal protein, except in areas where Hinduism is practiced. Consuming animal protein imparts status because it makes people stronger. This is a fact of evolution. The production of meat, dairy products, and fish, however, is problematic because of its high cost in land, water, and chemicals. A large intake of animal protein is also directly linked to lifestyle-related diseases in wealthy countries. It is therefore important to curb the per capita consumption of meat and (especially fatty) dairy products where this intake is too high, while making animal proteins available in countries where their consumption is too low. In order to feed the 9 billion people who will probably populate the earth in 2050, we need to increase our production of animal proteins by 73 percent, a substantially greater amount than the increase needed in grain production. Greenhouse effects, as well, make it imperative that we search for alternatives.

Paleontological studies have shown that insects were included in the diet of early humans. Interestingly, they are also part of the Judeo-Christian culture. In the Bible, grasshoppers were recommended, on the one hand (in Leviticus), and forbidden, on the other (Deuteronomy). The fact that it was necessary to forbid them indicates that there was a long tradition of consuming insects. For food taboos, there is seldom a clear-cut medical explanation; rather, they are of a symbolic value. This is certainly evident in the obvious aversion to insects present today in the Western world. Insects are considered creepy. Strange, actually, because we eat animals out of the sea that closely resemble them, such as shrimp, lobster, and eels. But then we call those animals seafood, and in other languages they are referred to as sea fruits as a way to obscure their animal origin.

The importance of insects lies not only in the fact that they are an alternative source of protein. Eating insects can change your perspective, allowing you to consider how you take your eating habits for granted. Nutrition not only is biology or history, but also has to do with customs and choice. Eating insects paves the way to eating many other animal species that are further down the food chain, such as snails and algae, which can also boost the global food supply.