We need history, certainly, but we need it for reasons different from those for which the idler in the garden of knowledge needs it, even though he may look nobly down on our rough and charmless needs and requirements. We need it, that is to say, for the sake of life and action.

Prologue

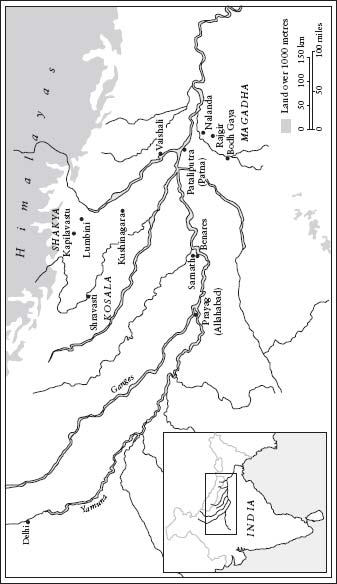

I N 1992 I MOVED to a small Himalayan village called Mashobra. Later that year, I began to travel to the inner Himalayas, to the Buddhist-dominated regions of Kinnaur and Spiti. These places were very far from Mashobra, but travel to them was easy and cheap: rickety buses that originated in the nearby city of Simla went hundreds of miles, across high mountains and deep valleys, to a town near Indias border with Tibet. I often went on these long journeys attracted by nothing more than a vague promise of some great happiness awaiting me at the other end.

I remember my first trip. The monsoons had just ended, with several dull weeks of fog and rain abruptly cancelled out by a series of sharp clear days. On that chilly, bright morning, the bus was late and crammed with nervous Tibetan pilgrims, peasants and traders, its dusty and dented tin sides already streaked with vomit.

Luck, and some pushing and shoving, managed to get me a seat by the window; and then, after that bit of luxury, the crowd, the bad road and the dust seemed not to matter. Everything I saw the sun leaping across and through dark pine forests, the orange corn cobs drying on slate roofs of houses lost in immense valleys and, once, a tiny sunlit backyard with a pile of peanut shells on the cowdung-paved ground seemed to be leading to an exhilarating revelation.

The day flew quickly past my window. But evening came cautiously, and the bus lost some of its cranky energy as it struggled up a narrow twisting road into the Sangla valley. Pink-white clouds blurred the snow peaks of the surrounding tall mountains as the river in the ravine below roared. The valley broadened at last. The mountains became even taller and more self-possessed. Long shadows crept down their rocky slopes and then over the green rice fields beside the river. Lights shone uncertainly through the haze ahead. Then, a long curve in the road brought them closer and revealed them as lanterns hanging from the elaborately carved and fringed balconies of double-storeyed wooden houses.

The bus began to climb again; the houses and the riverside fields receded. Boulders now littered the low barren slopes of the mountains where occasionally a glacier had petered out into muddy trails. Finally, at the end of the flinty snow-eroded road, the air growing thinner and thinner and Tibet only a few desolate miles ahead, there was a shadowy cluster of houses on a hill.

I was panting as I walked up a narrow cobblestone ramp. The bluish air trembled with temple bells. But the sound came from some other temple, for at this temple shyly nestled under a giant oak and festooned with rows of tiny white prayer flags there was only an old man hunched over an illustrated manuscript, a Tibetan, probably, judging by his face and the script on his manuscript, whose margins shone a deep red in the weak light from the lantern next to him on the platform.

The temple, though small, had a towering pagoda-like roof; the gable beams ended in dragon heads with open mouths. The carved wooden door was ajar and I could see through to the dark sanctum where, serene behind a fog of sweet-smelling incense, was a gold-plated idol of the Buddha: a Buddha without the Greek or Caucasian visage I was familiar with, a Buddha with a somewhat fuller, Mongoloid face, but with the same high brow, the broad slit eyes, the unusually long and fleshy ears, and the sublime expression that lacks both gentleness and passion and speaks instead of a freedom from suffering, hard won and irrevocable.

I had been standing there for a while before the old monk raised his head. Neither curiosity nor surprise registered in the narrow eyes that his bushy white eyebrows almost obscured.

We didnt speak; there seemed nothing to say. I was a stranger to him, and though he knew nothing of the world I came from he did not care. He had his own world, and he was complete in it.

He went back to his manuscript, wrapping his frayed shawl tightly around himself. Crickets chirped in the growing dark. A smell of fresh hay came from somewhere. Moths knocked softly against the oil-stained glass of the lantern.

I stood there for some time before being led away by the cold and my exhaustion and hunger. I found some food and a place to rest in the village. The long strange day ended flatly, its brief visions unresolved.

I spent a sleepless night in a farmers low attic, with the smell of old dust and dead spiders, and some slivers of moonlight. I was already up the next day when the roosters began to cry.

I went immediately to the temple, where there were worshippers Buddhist or Hindu: I couldnt be sure but the monk was nowhere to be seen. The morning arose from behind the snow-capped mountains. Then, suddenly, it overwhelmed the narrow valley with uncompromising light. Sharp knives glinted in the river. The village was bleached of its twilight mystery. The wooden chimneyless houses puffed thick blasts of smoke from open windows and doors. A long queue of mules carrying sacks of potatoes clattered down the cobblestone ramp. I was restless and wanted to leave. My return journey to Mashobra blended in my memory with other journeys I made to the Sangla valley in later years. But for many days afterwards, my mind rambled back to the temple, to that moment in the shadow of an oak before the Tibetan exile silently in tune with the vast emptiness around him, and I wondered about the long journey the monk had made, and thought, with an involuntary shiver, of the vacant years he had known.

It was around this time that I became interested in the Buddha. I began to look out for books on him. I even tried to meditate. Each morning I sat cross-legged on the dusty wooden floor of my balcony, facing the empty blue valley and remote mountain peaks in the north, which, I remember, turned white as that first autumn gave way to winter, and the apple and cherry trees around my house grew gaunt.

It seems odd now: that someone like myself, who knew so little of the world, and who longed, in one secret but tumultuous corner of his heart, for love, fame, travel, adventures in far-off lands, should also have been thinking of a figure who stood in such contrast to these desires: a man born two and a half millennia ago, who taught that everything in the world was impermanent and that happiness lay in seeing that the self, from which all longings emanated, was incoherent and a source of suffering and delusion.

I had little interest in Indian philosophy or spirituality, which, if I thought of them at all, seemed to me to belong to Indias pointlessly long, sterile and largely unrecorded past. I didnt see how they could add to the store of knowledge science and technology and the spirit of rational enquiry and curiosity that had made the modern world.

My interest in the Buddha seems even stranger when I recall how enthralled I was then by Nietzsche, among other western writers and philosophers. Probably like many other impoverished and lonely young men I was much taken by the idea that one could overcome despair and win from the world, through sheer will, the identity and security it seemed reluctant to give.