Contents

Guide

Page List

For Glenda

All of us go onto the ranchspiritually, mentally, emotionally, physically, and financiallybroken. But we each have a sliver of hope. The aliveness within us has a soft voice. Otherwise, none of us would have come here in the first place.

Eliza

CONTENTS

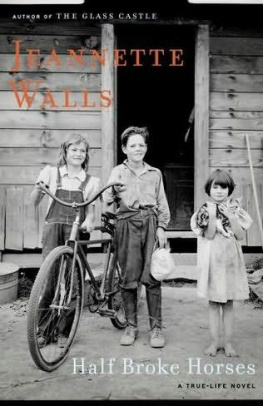

HALF BROKE

A t first it seemed like just another ranch asking me to help. Training horses and educating their owners has been my job for the last twenty years. I hear many stories of horse trouble. In those stories a lot of things go unsaid and, most likely, unnoticed. But I know that the slightest movementa flick of an ear, a shortening of breathis how a horse will try to communicate. If the owners had noticed this subtle language early on, the whole bad experience might have gone differently. But this call was different. Not once in my life had I heard of horses acting like this: scavenging, marauding, war parties of horses. I didnt think it could be true, and if it was, I certainly needed to see it.

This particular ranch is a prison. Most of the residents living here are multiple offenders, felons. They applied to come to the ranch from prison and have gone before a judge to have the term of their sentence finished here on the ranch. The whole operation is run by the residents themselves: no hired CEO, no lawyers, no counselors, no outside plumbers, no doctors. No jail guards. Statewide and county judges, probation and parole officers, court-appointed lawyersall interact and count on the older residents of this ranch to fulfill the legal sentencing requirements for each resident.

This ranch has run like this for almost fifty years. The oldest residents take the lead and teach each new arrival the essential skills to keep the operation of the ranch ongoing. Only a few of the residents have come in off the streets voluntarily, strung out on heroin, meth, or alcohol. They live at the ranch after hitting rock bottom. This ranch is here to save their lives.

Horses have always been part of the ranch. They live together with the residents on this seventeen-acre property, which sits along the banks of the Rio Grande in northern New Mexico. The herd roams free in the pastures. They gather in the automotive shop when it rains and snows, and in the woodshop when the flies get too bad. They forage through the ranch dumpsters for cookies, leftover baked goods, and Wonder Bread. At night they are chased by six to eight men, running behind them, into sizeable pens where they have shelter, water, and alfalfa hay. During the day they wander the property like giant gods with dominion over all things.

No one on the ranch knows very much about horses. They dont know that Wonder Bread and Tastykakes are not good forage for an animal that has browsed on grasses, flowers, and tree bark for thousands of years. Before I got the call, the horses had begun running in packs like dogs, chasing the residents when they brought the trash out from the cafeteria after breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The residents gathered in a tight circle next to the trash containers. They carved wooden poles in their woodshop that they carried to fend off each attack. Residents had been bitten, theyd been tripped and stepped on. A few had injuries to their ankles, arms, and wrists. Men and women, toughened by prison and living on the streets, ran as fast as they could for safety when the horses began their charge.

My first trip to the ranch was on a Sunday. Sunday is the one day of the week the residents have off from a grueling weekly work schedule. At the ranch, they have a livestock division. The residents working on livestock are required to feed and care for the horses, ducks, dogs, and cats that live on the property. There are two heads of the livestock division and about six other members who split duties of caring for the animals.

I learned on that first Sunday that the livestock division was run by two women, Flor and Sarah. Flor was in her thirties, a longtime heroin addict for fifteen years. She was in prison for a multitude of crimes, with the last term for robbing her mothers home. Her mother turned her in, feeling certain that prison was the safest place for Flor. Flor is a small woman with a big presence. When I first met her, she stood with her legs parted wide, her chest and shoulders open, arms draped by her side, as she looked me straight in the eye. Sarah was in her forties, a mother, a meth and heroin addict, and a prostitute since she was thirteen. When she spoke to me, her body wiggled like she was dancing. Her mouth held wrinkles that pointed the corners of her lips toward the ground.

Everything at the ranch, all the knowledge and skill it takes to keep the property in good order and the residents cared for and well fed, is supervised by the residents who have lived here the longest. The elder residents are the officials in charge. It is a long chain of knowledge handed down, one person at a time, ensuring that the strong traditions and standards of the ranch will continue. At one time there had been a chain of knowledge regarding how to care for the horses. That chain of knowledge had broken. Neither Flor nor Sarah had much experience with horses, yet they understood something was seriously wrong.

They went before the elders of the ranch and asked permission to reach into the community for help. Asking for and receiving help from outside the ranch is rarely needed. Most of the residents come from families with a long history of addiction, poverty, and gang crime. Some of them have never worked a job in their entire life. Each one, teach onethis is the way the ranch operates. Every four months the residents change jobs to learn a new skill: plumbing, cooking, auto mechanics. The older residents pass on their knowledge. Over one hundred residents live on the ranch at any one time. Drug addicts and criminals adjusting to life outside a conventional prison but still contained by twelve-foot adobe walls.

Thats when I got the call. I am a small-framed woman, weighing just over 120 pounds. I can be quiet and reserved when I first meet people and rarely make dramatic first impressions. My calm, restrained demeanor may not impress people, but horses take to it easily. In my work over the past twenty years, I have witnessed a wide variation of behavior when it comes to the horse-human relationship. On that first Sunday, I found myself in the middle of the most dangerous horse situation I had ever encountered.

March / 2013

T he men and women from the livestock team are sitting on tables and benches placed under the shelter of a small tack room, positioned a few yards away from the nighttime corrals. It is four in the afternoon, feeding time. Recently they have experienced bad accidents during the feeding routine. Arguments about whose fault it was and the question of how to fix the problems are on their minds. I introduce myself to everyone, as each member of the team rises to shake my hand and tell me their name. They begin to talk. The most recent accident, with Paul, keeps coming up. Paul was trampled by Hawk two days ago. His left wrist is wrapped in a support bandage, and he limps along dragging his right leg.

How can we keep them from running us over? I mean, they dont listen, Paul explains. Paul is a tall man, with a thick neck and broad shoulders. They run right through us, like we arent even here, he tells me. His ear lobes have wide open holes at their end. I see straight through them like Im looking through tiny windows.