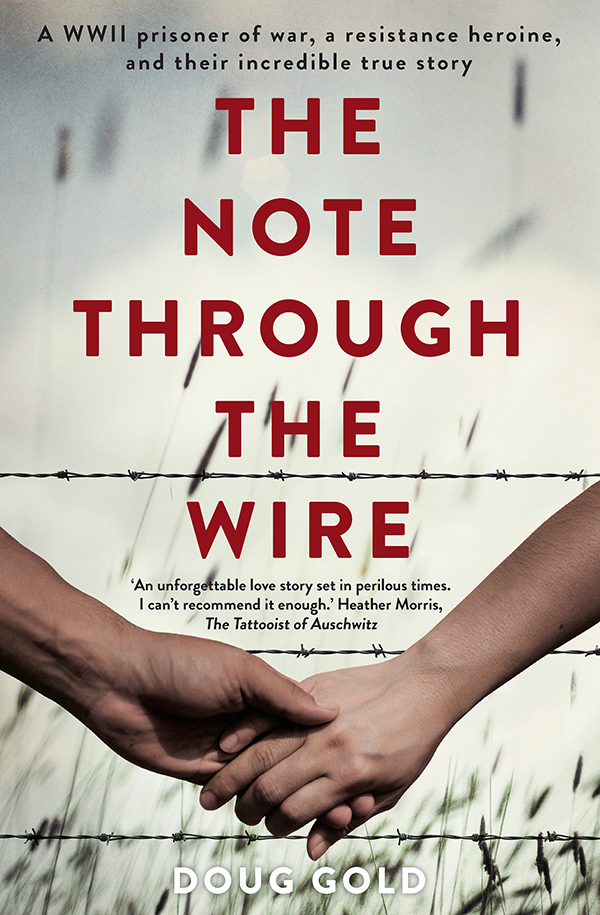

First published in 2019

Text copyright Doug Gold, 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Allen & Unwin

Level 3, 228 Queen Street

Auckland 1010, New Zealand

Phone: (64 9) 377 3800

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.co.nz

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

ISBN 978 1 98854 709 1

eISBN 978 1 76087 107 9

Design by Megan van Staden

Maps by Area Design

Photographs on page from the authors family collection

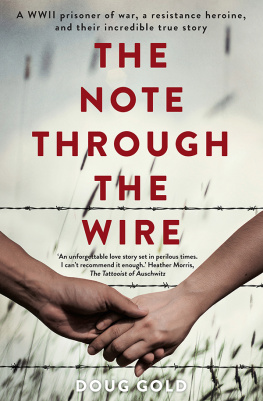

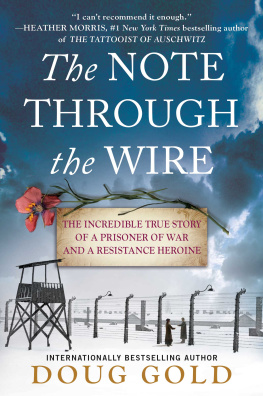

Cover imagery by Nicola Smith/Trevillion Images, Suparat

Malipoom/Getty Images and Maravic/iStock

In memory of Bruce Murray and Josefine Lobnik, who found love in the midst of a bloody conflict

Contents

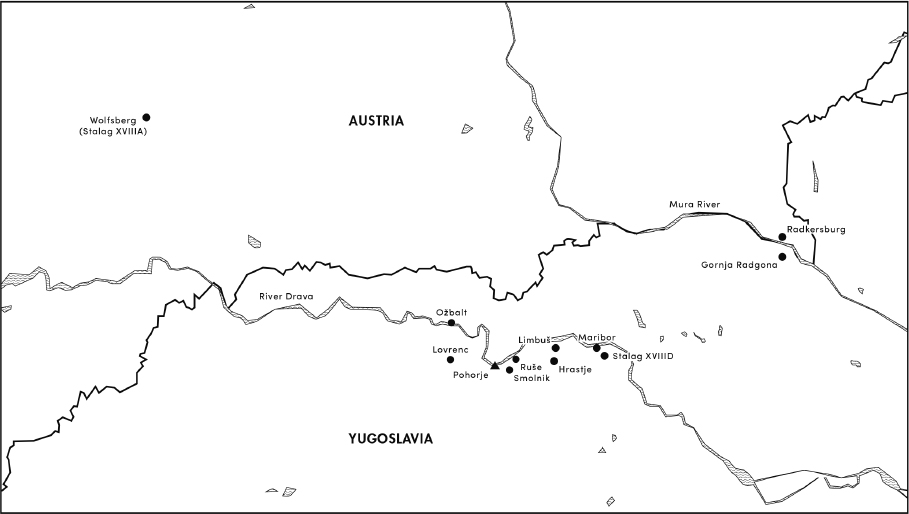

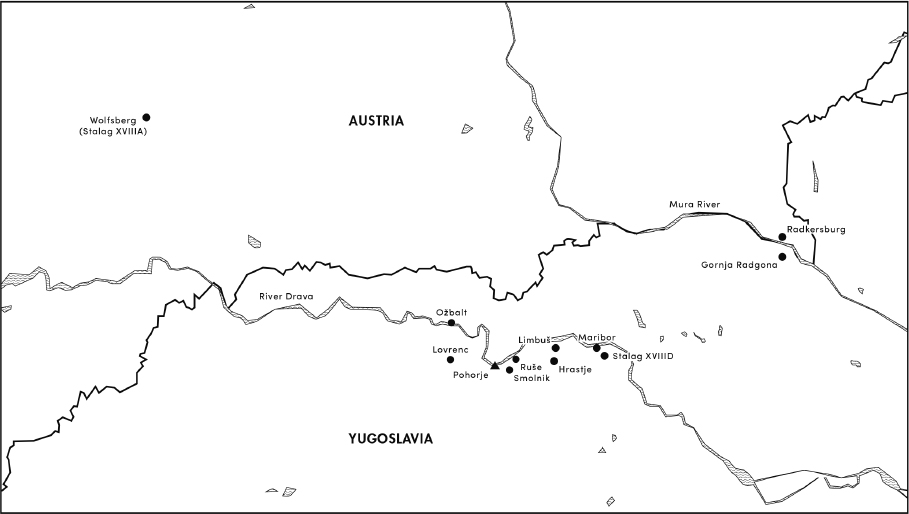

Bruces route from Radkersburg to Odessa in 1945

Maribor and surrounds

He was nursing a sledgehammer hangover. It took Bruce Murray several minutes to reorientate himself. The hut gradually came into focusthe rough timber of the walls, the muddy floorboards, the grimy window in the door.

It was Sunday. That was a good thing. That was a bloody good thing, considering the state he was in. He imagined what it would be like if the German guards came hammering at the door, as they did on most other days, ordering him to fall in for a compulsory work detail at some Slovene factory or, worse, at one of the railway sites near the Maribor POW camp.

He shuddered. Disconnected pieces of the previous evening came back to him. Shouts of laughter. The fug of smoke, of course. The eye-watering burn of the homebrewed hoochsome infernal potion the boys had concocted in secret from filched potatoes and hoarded sugar, or so he understood.

Lofty. Thats right. It was Lofty Colliers twenty-first birthday, and this had seemed like enough of an occasion to break out the booze. Bruce had had hangovers before, more than he cared to remember, but this one was a real doozy. It felt as though a pneumatic drill was boring through his temple and there was a coating of cement on his tongue that fixed it to the roof of his mouth. Now his guts were churning.

He groaned.

The mood had swung wildly over the course of the evening. First there was hilarityjokes and laughter and good fellowship. Then it had developed a hard edge, when the latest outrage committed by some guard or another riled the men. Inevitably, it had grown maudlin, as stories and reminiscences of home were shared. Towards midnight, they had rallied, and the singing had begun. Some time and several tin cups of grog later, the joy had leached from it all again as many hoarse throats joined a chorus of Auld Lang Syneit sounded more like Old Lands Shine in their rendition. There were tears. Bruce might have shed a few himself.

After that, he didnt remember much.

The hut reeked. His shirt reeked. He reeked. He had to get out.

Bruce heaved himself into a sitting position and swung his legs over the edge of the bunk, his coarse grey blanket slithering to the floor. The hut spun, and Bruce belched ominously. Steeling himself, he lurched to his feet, averted his eyes from the hazy scrap of mirror, pulled on his boots, shrugged into his greatcoat and staggered to the door. A gust of freezing air greeted him as he opened it, and he screwed up his eyes against the glare from the snow. Perhaps, he thought, sitting out in the bitter wind would purify him, purge him of the toxic aftermath of the night before. He sat heavily on the upturned Red Cross crate where he sometimes sat in warmer weather, drew his coat about him and wondered whether a ciggy would make him feel better or worse.

Thats where Frank Butler found him.

Get up, ya ugly sod, Frank said.

Piss off, Frank, Bruce replied.

Come on, Brucie. Get off yer arse. Lets take a turn, blow out the cobwebs.

Frank grabbed Bruces arm and heaved him to his feet. It was their routine on Sundays to take a stroll around the perimeter of Stalag XVIIID: partly for the exercise, partly because it gave them another opportunity to taunt the goons with jibes as barbed as the wire surrounding them, mostly to relieve the unrelenting boredom.

Cor, you look a right bloody mess, Frank said, eyeing him sideways. Insults were the stock-in-trade of their conversation, but Frank meant it. By this hour of the morning, Bruce was usually freshly scrubbed, his hair combed and slicked down, and he would have done what he could with his clothes. Not today.

It was all Bruce could do to grunt in reply.

They walked in companionable silence, an inch of fresh snow squeaking beneath the soles of their boots. The gloom overhead thinned a little and the light brightened. It was agony on Bruces bleary eyes. He closed them tightly and gritted his teeth.

Hello, Frank breathed softly beside him. What have we here?

Bruce opened his eyes.

They were thirty yards from a point on the southern perimeter fence that was out of the direct eye-line of the guards in the watchtowers. There was a figure standing motionless on the other side of the wirea brave or desperate thing to do since, needless to say, the guards didnt exactly encourage interaction between the locals and the camp inmates. It was an old woman, to judge from her attireshe wore a shapeless woollen dress and a black-fringed knitted shawl.

Her presence there was something out of the ordinary, something that stood out from the monotony of camp life.

Come on, Bruce said. Lets see what she wants.

Frank looked all around them carefully. There werent any guards in sight, but that meant little. A goon might appear at any moment.

Best not, he said. Theyll shoot you if they see you.

Nah, said Bruce. Shell be right.

The hangover had relented a little. He had regained his will to live.

Frank stayed where he was. Bruce walked briskly to the wire. Unlike most prisoner-of-war camps, which had two wire perimeter fences, one inside the other with ten yards of dead ground between them, Stalag XVIIID had been a Slovene Army barracks and was surrounded by only a single high wire fence. Despite the dangers, the locals occasionally traded itemseggs, bread, woollen mittensfor rare luxuries such as the tinned meat or chocolate bars that came in Red Cross parcels.

The woman watched him approach. Bent and shapeless as she was, she reminded Bruce of old Sis Moore who used to terrorise the kids of his neighbourhood when he was growing up. It was rumoured she would beatand even eatkids who strayed onto her property.

Hello, he said, as he neared the wire, and smiled. She stepped forward, and held out her hand towards him. His smile faltered as he met her eyesgreen and unmistakeably youthful beneath the fringe of the shawl.