Contents

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright 2016 Deborah Campbell

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2016 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Alfred A. Knopf Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint from the following: Glain, Stephen. The Arab Street, Handbook of USMiddle East Relations: Formative Factors and Regional Perspectives, Looney, Robert E., Editor. Routledge, 2009, 172173.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Campbell, Deborah, author

A disappearance in Damascus : a story of friendship and survival in the shadow of war / Deborah Campbell.

Includes bibliographical references.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-345-80929-2

eBook ISBN 978-0-345-80931-5

1. Mahmood, Ahlam A. 2. Campbell, Deborah. 3. Political prisonersSyriaBiography. 4. Iraq War, 20032011RefugeesSyriaBiography. 5. RefugeesSyriaBiography. 6. RefugeesIraqBiography. 7. JournalistsCanadaBiography. I. Title.

DS98.72.M33C34 2016365.45092C2014-906791-7

Ebook ISBN9780345809315

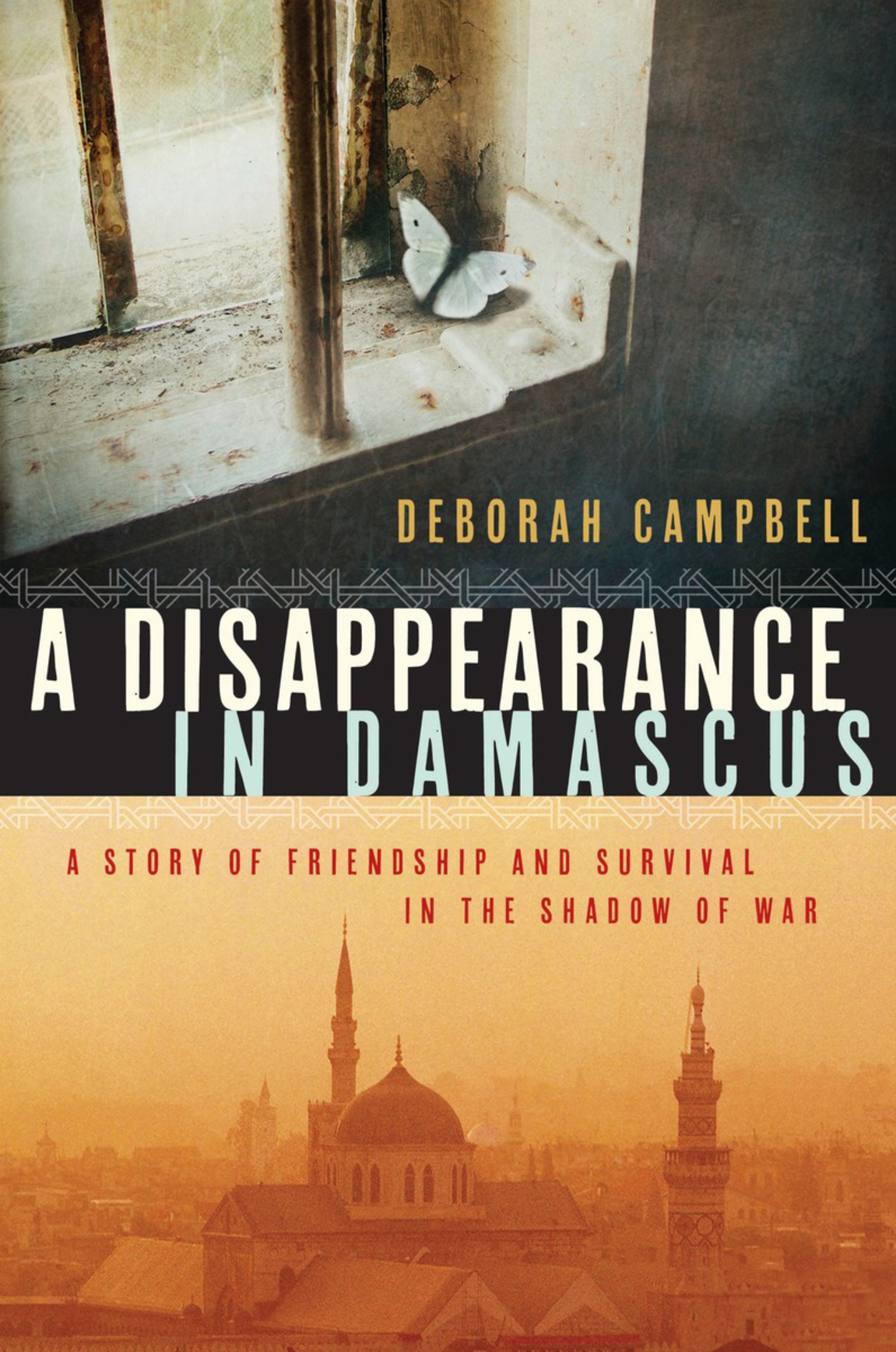

Cover images: (trapped butterfly) Mark Owen / Arcangel Images;

(Damascus skyline) Philip Lee Harvey / Corbis

v4.1

a

FOR RON

An eye for an eye, but always the wrong eye.

WILLIAM SAROYAN

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

DID I FIND HER or did she find me?

I wrote that question in my reporters notebook soon after I met Ahlam, the Iraqi woman who was to change my life. It was 2007, and we had only recently begun working together in Damascus. I was the journalist; she was my interpreter and guidemy fixerconnecting me to refugees from Iraq. An irrepressible extrovert with a keen sense of the absurd, she was the sort of person who appeared at ease in chaosalways with a dozen projects on the go, always with a cigarette in one hand and a phone in the other. In her early forties, she had a university education and the instincts of a street fighter. As she led me ever deeper inside the hidden world of the war she had fled, and into the increasingly unstable country of Syria where she had sought refuge from Iraq, she showed me what survival looks like with all the scaffolding of normal life ripped away.

When I wrote that question, I had no idea what it would come to mean nearly a year later, when she was taken from me by agents of the secret police. How had I lost her? Was her disappearance somehow my fault? Caught in a web of fear and suspicion, I wanted to run for cover but knew I had to stay to look for her, so I began to question myself as a journalist would, wondering what I really knewabout her, about trust and friendship and betrayal, about the deepening crisis overtaking Syria, about the friends and strangers who surrounded me, about the thin line between courage and recklessness in the face of dangeras I struggled to put together the pieces that would tell me who had taken her and why she had disappeared.

Chapter 1

EXODUS

ALONG THE TWO-LANE HIGHWAY from Syrias capital city of Damascus, where it approaches the border with Iraq, anti-aircraft batteries scanned the dome of noonday sky. Here and there an army tank rumbled over hot sand along a barren landscape that looked like the surface of Mars. Next to the highway, a crop of bored young Syrian soldiers slouched on boulders around a commander making diagrams on a chalkboard propped up against another boulder.

Gripped by the anticipation I always feel when I am about to plunge into an unknown situation, I was greeted by a weathered road sign that broke the tension. It read, in English, Happy Journey. A lovely sentimentI had to take a picture. It was the peak of Iraqs civil war, and absolutely no one was travelling into Iraq on a happy journey; a million and a half refugees had already fled the other way, to Syria, and they were happy for nothing but to be alive. In the sliver of shade the sign provided from the scorching sun, people stood with their suitcases, gazing back towards the country they had left behind.

Beyond them, past a giant parking lot, more Iraqis were streaming towards me into Syria, disgorged from buses and SUVs. In the early days of the exodus there had been time to make arrangements, to sell houses and cars and belongings. Now the entire middle class was on the run: the doctors and professors and librarians, the filmmakers and painters and novelists, the engineers and accountants and technocratsthe people who thought things, made things, kept things humming. Half the professional class had already left, and two thousand more funnelled through this unimpressive desert crossing every day. Some looked dressed for the office, women in high heels and oversized sunglasses, men in pleated dress pants and button-down shirts, as if theyd walked out of work, grabbed the kids and the cash, and just left.

Watching them, the very people Id come to the border to talk to, I almost didnt see the border guard as he emerged from a makeshift checkpoint and stepped in front of the car Id hired. The checkpoint, despite the barred windows, was more shepherds hut than blazing emblem of officialdom. But officialdom it was. He waved my driver to park in the dirt to the side. As I was getting outjamming my notebook into the bag that carried my camera and audio recorder, rooting around for my passport, ignoring the furnace blast of heata large white press van pulled up beside me. The door slid open and an American TV news crew stepped out.

It was rare to meet other journalists in Syria so I was surprised. I had been doing my best to stay under the radar, to avoid undue attention, and here I was arriving with the cavalry. Waiting in the shade cast by the checkpoint while our documents were taken away to be examined, I asked the cameraman, a frenetic thirtyish guy with a shaved head, where he was based.

Dixie, he said.

Dixie?

He laughed. Thats our code for the Zionist entity, as they say around here. Jerusalem, like Beirut, was a hub for the international press. I spend most of my time on the beach in Tel Aviv. For this short-term assignment the news team was staying at the Four Seasons in Damascus. They had taken the same highway from the city to the border crossing this morning that I had.