Old Man of the Colonial Office

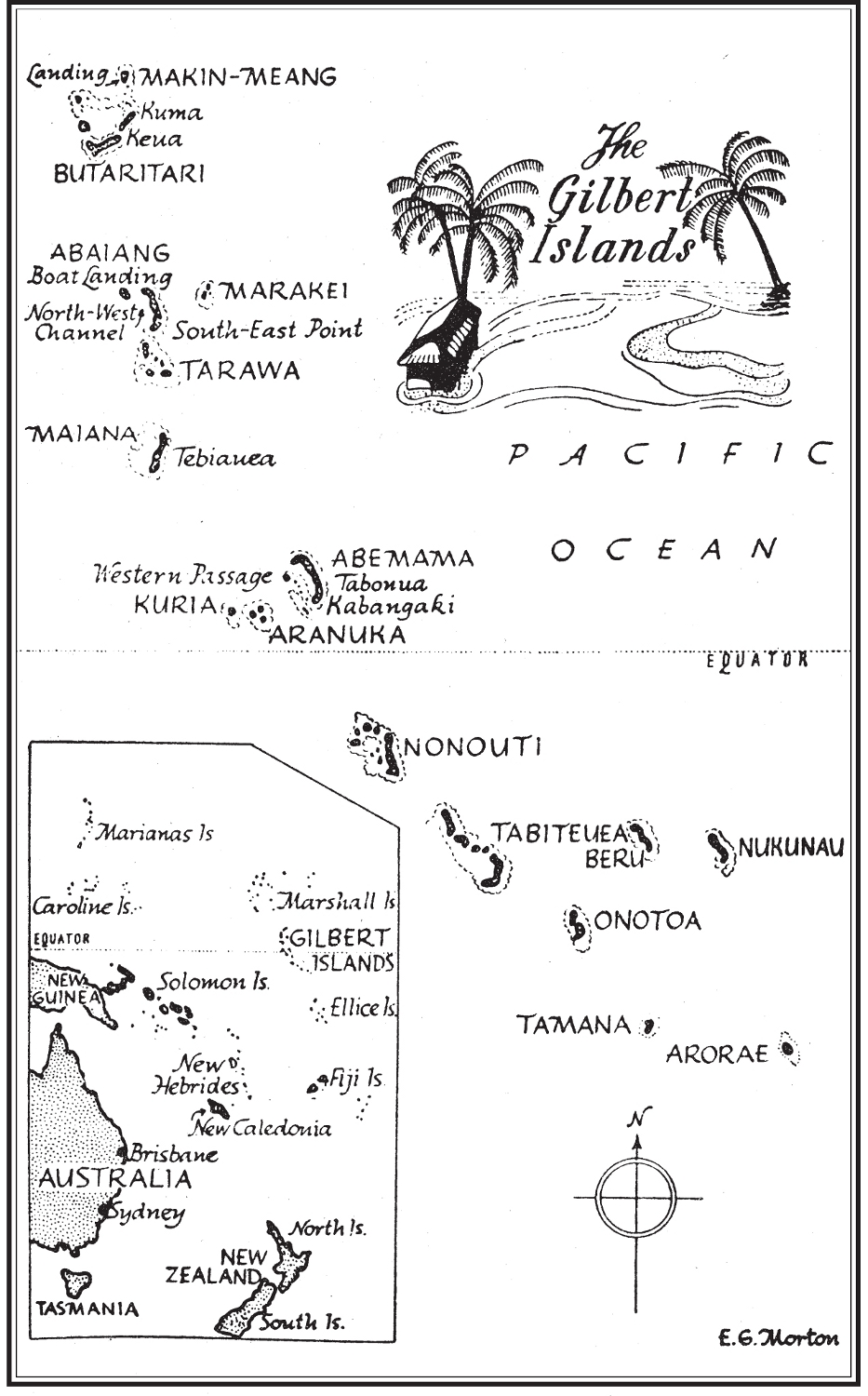

I was nominated to a cadetship in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Protectorate at the end of 1913. The cult of the great god Jingo was as yet far from dead. Most English households of the day took it for granted that nobody could be always right, or ever quite right, except an Englishman. The Almighty was beyond doubt Anglo-Saxon, and the popular conception of Empire resultantly simple. Dominion over palm and pine (or whatever else happened to be noticeably far-flung) was the heaven-conferred privilege of the Bulldog Breed. Kipling had said so. The colonial possessions, as everyone so frankly called them, were properties to be administered, first and last, for the prestige of the little lazy isle where the trumpet-orchids blew. Kindly administered, naturally nobody but the most frightful bounder could possibly question our sincerity about that but firmly too, my boy, firmly too, lest the schoolchildren of Empire forget who were the prefects and who the fags. Your uncles meaning every man Jack of your fathers generation, uncle or not, who cared to take you by the ear all said youd never be a leader if you weakened on that point. It was terrifying, the way they put it, for Stalky represented their ideal of dauntless youth, and you loathed Stalky with his Company as much as you feared him; but you were a docile young man, and, as his devotees talked, you felt the seeds of your unworthiness sprouting into shameful view through every crack in your character.

The Colonial Office spoke more guardedly than your uncles. It began by saying that, as a cadet officer, you were going to be on probation for three years. To win confirmation as a member of the permanent administrative staff, you would have to pass within that time certain field-examinations in law and native language. This seemed plain and fair enough, but then came the rider. I forget how it was conveyed, whether in print or by word of mouth; but the gist of it was that you could hardly hope to be taken on as a permanent officer unless, over and above getting through your examinations, you could manage to convince your official chiefs overseas that you possessed qualities of leadership. The abysmal question left haunting you was did the Colonial Office mean leadership in the same sense as Kipling and your uncles? If it did, and if you were anything like me, you were scuppered.

I was a tallish, pinkish, long-nosed young man, fantastically thin-legged and dolefully mild of manner. Nobody could conceivably have looked, sounded or felt less like a leader of any sort than I did at the age of twenty-five. Apart from my dislike of the genus Stalky, I think the only positive things about me were a consuming hunger for sea-travel and a disastrous determination to write sonnets. The sonnet-writing had been encouraged by Arthur Christopher Benson at Cambridge; the wanderlust had started to gnaw at my vitals at school, when I read that essay of Froudes Englands Forgotten Worthies especially the part of it that pictured how Humfrey Gilbert met his end in the ten-ton frigate Squirrel, sitting abaft with a book in his hand, giving signs of joy to his fellow-adventurers in the Golden Hinde and roaring at them through the wild Atlantic gale that engulfed him, We are as near heaven by sea as by land so often as they approached within hearing. I tried at Cambridge to cram some of my feelings about that, and the seas lure in general, into a sonnet of dubious form

She called them with the voices of far lands

And with the flute-like whispering of reeds,

With scents of coral where the tide recedes,

With thunderous echoes of deserted strands.

She babbled the barbaric lilt of tongues

Heard brokenly in dreams; she strung the light

Of swarthy-smouldering gems across the night;

She wrung their hearts with haunting of strange songs.

She witched them with her ancient sorceries

And lo! they knew the terrible joy of ships

Gone questing where the moons last footstep is,

And stars hold passionless converse overhead

While mariners are drawn with writhen lips

Down, down, deep down, among her voiceless dead.

Arthur Benson was pained at the rhyme-pattern of the octave, but said the thing sounded sincere and showed promise. I was unwise enough to bring his kindly letter to the notice of some of my uncles. They only said he ought to have known better; after all, he had had every chance, dammit, as the son of an archbishop! So, Benson, as a moral prop, was out. But I had acquired at school and Cambridge some kind of competence at cricket and other sports, which kept them always hoping for the best. When I became, first secretary, and then, in the normal course, captain of my college cricket XI, they began to believe I really might be on my way to vertebrate life. But they could not have been more deeply mistaken. As secretary, I invariably took orders from the captain; as captain, I invariably took orders from the secretary, while the team invariably played the game as if neither of us were there. The worst of it was, I loved it. If ever I had previously entertained a notion that I might enjoy ordering people around, that experience certainly disabused me of it.

The fear of being packed home from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands in disgrace, after three years of probation, for having failed to become the kind of leader my uncles wanted me to be, began to give me nightmares. A moment came when I felt that the instant sack for some honest admission of my own ineptitude would be easier to bear than that long-drawn-out ignominy. In any case, I decided, someone at the top ought to be warned of my desperate resolve never to become like Stalky. It sounded rather fine, and lonely, and stubborn, put like that; but I fear I didnt live up to the height of it. I did, indeed, secure an interview at the Colonial Office, but my nearest approach to stubbornness with the quiet old gentleman who received me there was to confess, with a gulp in my throat, that the imaginary picture of myself in the act of meting out imperial kindness-but-firmness to anybody anywhere in the world, made me sweat with shame.

The quiet old gentleman was Mr Johnson, a Chief Clerk in the department which handled the affairs of Fiji and the Western Pacific High Commission. That discreet title of his (abandoned today in favour of Principal and Secretary) gave no hint of the enormous penetrating power of his official word. In the Western and Central Pacific alone, his modest whisper from behind the throne of authority had power to affect the destinies of scores of races in hundreds of islands scattered over millions of square miles of ocean. I was led to him on a bleak afternoon of February, 1914, high up in the gloomy Downing Street warren that housed the whole Colonial Office staff of those days. The air of his cavernous room enfolded me with the chill of a mortuary as I entered. He was a spare little man with a tenuous sandy beard and heavily tufted eyebrows of the same colour. He stood before the fire, slightly bent in the middle like a monkey-nut, combing his beard with one fragile hand and elevating the tails of his cut-away coat with the other, as he listened to my story. I can see him still, considering me over his glasses with the owlish yet not unkindly stare of an undertaker considering a corpse. (Senior officials in the Colonial Office dont wear beards today, but they still cultivate that way of looking at you.) When I was done, he went on staring a bit; then he heaved a quiet sigh, ambled over to a bookcase, pottered there breathing hard for a long while (I think now he must have been laughing), and eventually hauled out a big atlas, which he carried to his desk.