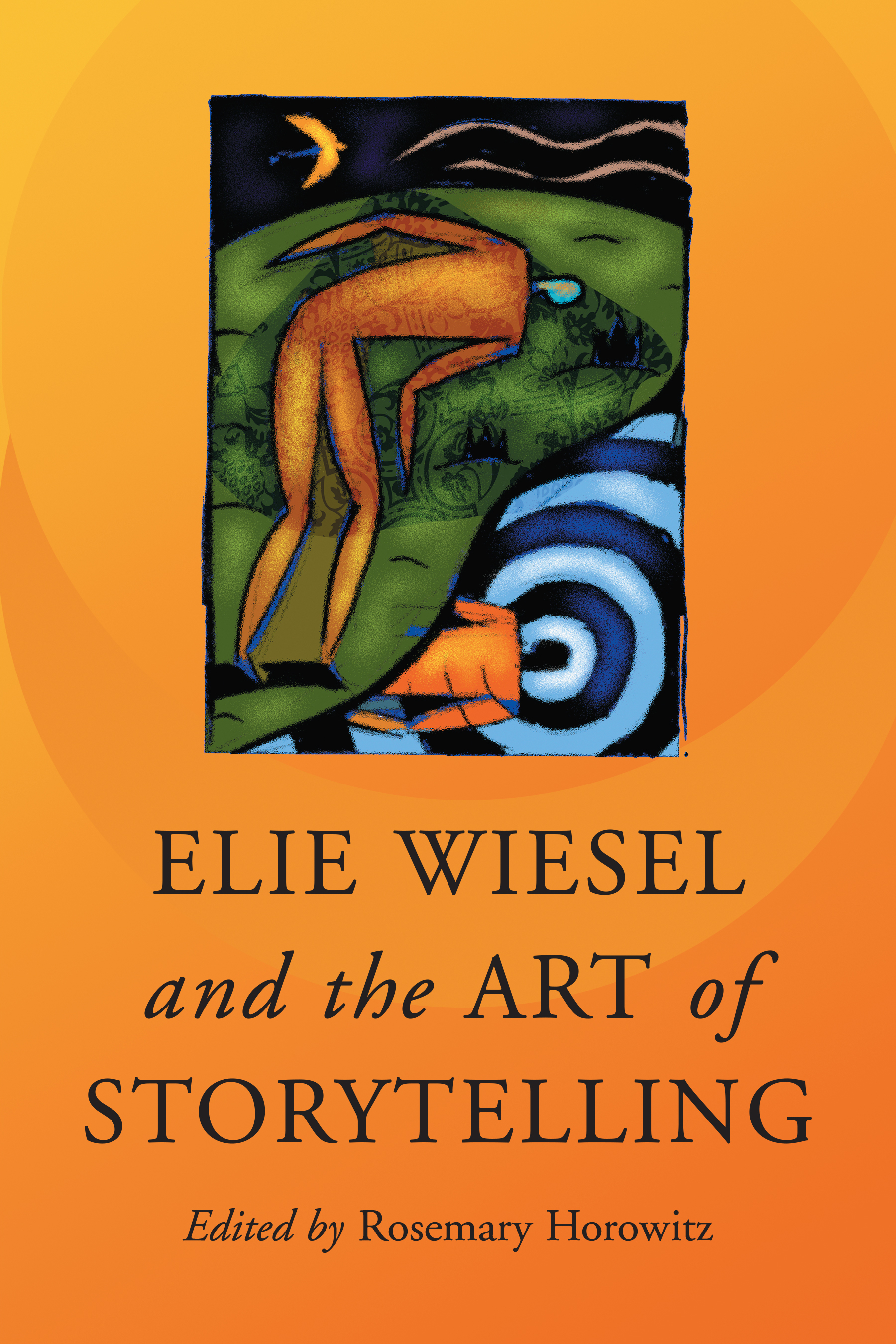

Elie Wiesel and the Art of Storytelling

Edited by Rosemary Horowitz

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-0-7864-8268-9

2006 Rosemary Horowitz. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover art 2006 Image Zoo Illustrations

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Preface

On October 14, 1986, the Nobel Committee named Elie Wiesel as the recipient of that years Peace Prize. The press release announcing the award notes that:

Wiesel is a messenger to mankind; his message is one of peace, atonement and human dignity. His belief that the forces fighting evil in the world can be victorious is a hard-won belief. His message is based on his own personal experience of total humiliation and of the utter contempt for humanity shown in Hitlers death camps. The message is in the form of a testimony, repeated and deepened through the works of a great author.

The repetition of message underscores the committees position that Wiesels beliefs about peace and justice permeate his substantial oeuvre. By contrast, Wiesel calls himself simply a teller of stories. Given that, it was not surprising that his Nobel lecture, entitled Hope, Despair and Memory, delivered on December 11, 1986, begins with a story. He starts the lecture by recounting an episode between the Hasidic master Baal-Shem-Tov and his servant, each of whom as a punishment lost the ability to pray. When pressed by his master to recall anything, the servant says that he remembers only the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. So, the two men begin to recite the letters, in effect, turning the alphabet into a prayer. Their passionate recitation was enough to restore the masters memory and undo the punishment. Wiesel explains that the story demonstrates the power of prayer, as well as the importance of memory. Wiesel continues the lecture by delving more deeply into the role of memory in contemporary affairs. At the end of his speech, Wiesel again mentions the Baal-Shem-Tov in order to re-emphasize that the need to remember is as great as ever. By connecting Hasidic and modern concerns, Wiesel reminds the audience that memory provides hope for all people. It is this ability to draw from religious, folk, and secular sources for diverse audiences that makes Wiesel a master storyteller. This collection of essays is about that mastery.

The authors of the essays in this collection discuss Wiesel as a storyteller by examining his texts from a variety of perspectives. Some of these writers focus on the religious influences on Wiesels writing; others on the secular influences; and still others on the transformative effects of his stories on teachers and students. Taken as a whole, the essays cover a wide range of Wiesels books. For those readers primarily familiar with Night, this collection will serve as an introduction to the breadth of Wiesels writing. For those readers already familiar with his writings, this collection will yield new insights about his works. The ultimate goal is to deepen the appreciation of Wiesels storytelling for all readers.

Introduction

Storytelling is a quintessential human activity. Yet, where people tell stories; the ways people tell stories; the purposes served by stories; and the values, attitudes, and beliefs toward stories vary across communities. Historical, economic, class, social, religious, gender, and other factors also affect stories and storytelling. Without a doubt, storytelling is a complex, fascinating phenomenon. There are many ways to explore that complexity. One way is to study the work of a master storyteller. Taking that approach, this volume looks closely at the works of Elie Wiesel, who is considered by many to be such a storyteller. Wiesels mastery comes from his ability to adapt religious, folk, and secular texts and experiences for various audiences using a variety of genres. Combined with that is his ability to elevate storytelling to an ethical level. For him, storytelling is a form of activism. Elie Wiesel is the embodiment of Walter Benjamins definition of an ideal storyteller. To Benjamin, the storyteller

has counselnot for a few situations, as the proverb does, but for many, like the sage.... His gift is the ability to relate his life; his distinction, to be able to tell his entire life. The storyteller: he is the man who could let the wick of his life be consumed completely by the gentle flame of his story. This is the basis of the incomparable aura of the storyteller, in Leslov as in Hauff, in Poe as in Stevenson. The storyteller is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself.

Like the writers on Benjamins list, Wiesel draws on his lifes experiences and uses them to teach his readers and listeners. He also uses them to promote a standard of conduct. To understand Wiesels genius, though, it is first necessary to identify the sources of his storytelling in order to provide a context from which to more deeply appreciate his work.

An Overview of Jewish Storytelling

In her research, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimlett finds that for Eastern European Jewry stories are important and storytelling is frequent in this culture. This coupling of writing and speaking suggests that Eastern European Jews believe their oral and written storytelling practices are interrelated.

Along with the Scriptures and the Midrash, the rabbinical commentary on the scriptures, and the Talmud and the Aggadah, the commentary on the Torah, the works specifically noted by Kirshenblatt-Gimlett, there are other Jewish religious texts. These include the Zohar, the kabbalalistic commentary on the Torah, as well as the collections of hasidic tales. This body of sacred works contains a treasure of stories. In addition to these religious texts, there are the folk texts, including lore, legends, proverbs, and tales. Although the religious and folk texts have extremely different purposes, they are each comprised of stories and are also sources for stories. Modern Jewish literature may also be added to this mix.

Since Jewish storytelling has its religious, folk, and secular aspects, its storytellers have varying degrees of religiosity. Some practitioners emphasize the religious traditions; others the folk ones. Examples of present-day storytellers with different approaches to their practice are Peninnah Schram and Yitzhak Buxbaum.

Peninnah Schram is the founder and director of the Jewish Storytelling Center, a program offered by the 92nd Street Y in New York City. She offers storytelling workshops and tells stories in Jewish and nonJewish settings to Jewish and nonJewish audiences. Religious and folk sources are foundational to her work. For example, in Jewish Stories One Generation Tells Another, she recalls that her fathers biblical, Talmudic, and midrashic tales along with her mothers folktales, teaching tales and proverbs are the sources for her storytelling. Given this goal of intergenerational legacy, her emphasis is on the folk aspects of storytelling, especially, the transmission of culture.

Next page