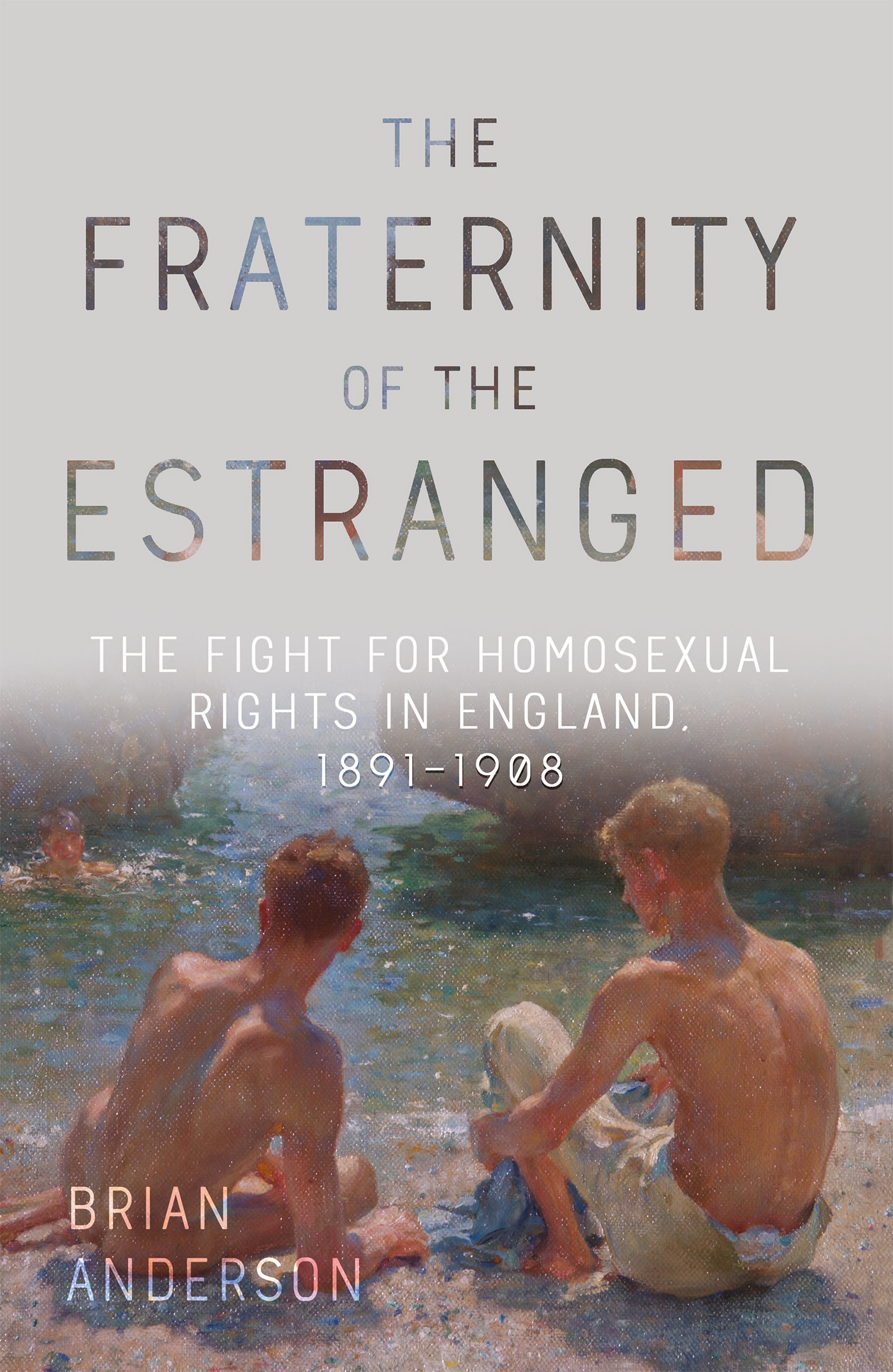

The Fraternity of

the Estranged

The Fight for Homosexual Rights in England

18911908

Brian Anderson

Copyright 2018 Brian Anderson

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Cover Artwork credit to Henry Scott Tuke (1858-1929), The Critics, with acknowledgment to the Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum for permission to reproduce it.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: books@troubador.co.uk

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1788034 876

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

For HC

Authors Note

Although this book resonates with contemporary academic research, in the fiftieth year since the decriminalisation in England and Wales of sexual relations between men in private, it is intended to speak principally to the LGBT community and, in a time more accepting of sexual diversity, to a wider readership. For many, Carpenter and Symonds remain dead to the world: their brave stand against persecution and intolerance not widely known. This narrative recounts the writing of important books, but it also offers a glimpse of what it was like to be homosexual in late-Victorian England.

Contents

Introduction

J uly 2017 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the decriminalisation in England and Wales of sex between two men in private. The law that had made such relations a crime had been passed in 1885, and remained in place for 82 years. But this restriction on same-sex love did not go unchallenged: between 1891 and 1908 three books appeared in England on homosexuality and the rights of homosexual persons. They were written by two homosexual men, Edward Carpenter and John Addington Symonds, and a third, Havelock Ellis. Setting out in life as young university dons, Carpenter and Symonds seemed the least likely of individuals to court notoriety as defenders of homosexuality, whilst the shy and retiring Ellis was a most improbable student of sex.

At the time, the study of what was then called sexual inversion was the almost exclusive preserve of writers on the European continent. Books on homosexuality that circulated freely there were hardly known in England, where, apart from its occasional discussion in medical journals, anything published on the subject was liable to be prosecuted for obscenity. Men who loved men were pushed to the margins, in a society where masculinity was strenuously upheld. In such a hostile environment, the appearance of these publications was highly significant. They were the first English contributions to the scientific understanding of homosexuality, and at the same time opened the long fight for the legal recognition of same-sex love that was finally won in 1967.

The special circumstances under which these books came to be written has not before been comprehensively documented. Here, through a combination of history, biography and textual analysis, the full story of the individuals who opposed this legislation and argued for homosexual equality is told. And, as the hazardous progress of these books towards publication is recounted, what was written is critically examined.

Chance pervades this narrative at every level. If certain events had not combined with the twists and turns of coincidence and circumstance, it is highly unlikely that any of these ground-breaking books would even have been conceived, let alone published. There would be nothing to tell if Carpenter had not discovered the homoerotic poetry of Walt Whitman at a time when he was deeply troubled by his homosexuality. Equally, if, after a crisis of belief, he had been able to resign as an Anglican curate but remain at his Cambridge college. When this was denied him, he became a peripatetic lecturer in the industrial towns of northern England, which radicalised him and brought him into contact with Ellis.

Similarly, if Symonds had not been forced to leave his Oxford college after a homosexual scandal, and had not also read Whitman at a time of crisis over his homosexuality. And if he had not abandoned the study of law for literary criticism, he would not have been approached by Ellis to contribute to a series of books that he was editing. In turn, this led to their collaboration in the writing of what turned out to be a fateful book on homosexuality.

Further, this story could not be told if the adolescent Ellis had not been taken to Australia by his sea captain father. Alone in the outback, where books were his only consolation, by chance he came across James Hintons Life in Nature ,

Finally, there is a fourth individual in this story, without whose intervention the history of homosexual law reform in England may have taken an entirely different path. In 1885, Henry Labouchre, the Member of Parliament for Northampton, succeeded in having a five line clause inserted into a piece of legislation that had nothing to do with sex between two men. It was its inclusion in the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act that made any intimate behaviour between men, whether in public or in private, potentially a criminal act. It would ensnare countless individuals before it was revised in 1967.

The iconoclastic poet Walt Whitman was the dominant presence in the lives of Carpenter and Symonds. He is woven into this story. In fear of the rigid taboo against the physical expression of their homosexuality, early in life both adopted a romanticised form of male-loving: an aesthetic idealization of their erotic instincts. Whitmans fervent espousal of male comradeship sanctioned the expression of their sexual natures but, more importantly, the empowerment to write about homosexuality flowed directly from him. Of discovering Whitman, Carpenter recalled: I find it difficult to imagine what my life would have been without it. that Ellis first came to know him.

It was when Symondss friendship with Ellis grew, that he asked him if he would take a book by him on homosexuality, for a series of scientific texts then under his editorship. He had written and privately circulated two monographs on homosexuality, which were outcomes of personal and contemporary events in his life. Both were defences of homosexuality, but in origination and purpose were essentially different. The first, which is referred to throughout as the Greek Problem, Person Act of 1861, the crime of buggery, if no longer a capital offence, remained in place, but at the instigation of Labouchre, the 1885 Act introduced the misdemeanour of gross indecency between male persons. Symonds wrote the Modern Problem to contest this legislation, by advancing a case for the decriminalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adults that took place in private. It was a political manifesto: the first to fully address the plight of homosexuals in England.

When the cautious Ellis prevaricated over taking a book on homosexuality for his series, considering it too risky, Symonds, out of the blue, suggested that they might write a book together on the subject. His approach was timely, as unbeknown to him, Ellis was preparing to make the study of human sexuality his lifes work. But of much more significance, he was equally unaware that, at this very time, Ellis was facing a personal crisis, after discovering that the woman who he had married only six months earlier was lesbian. This was the decisive factor in Elliss decision to collaborate with Symonds on the writing of Sexual Inversion, the book for which he is now best known . If Ellis had not agreed to collaborate, this book would never have been written. Acutely aware of Victorian attitudes towards homosexuality, Ellis knew that, rather than collaborating on a book on the subject, he should have passed it over as an unpleasant topic on which it was not wise to enlarge. Later, he would acknowledge that writing the book was a mistake, and claimed that it had never been his intention to launch his career as a sexual theorist with such a publication. He described the time spent on it as this toilsome excursion.