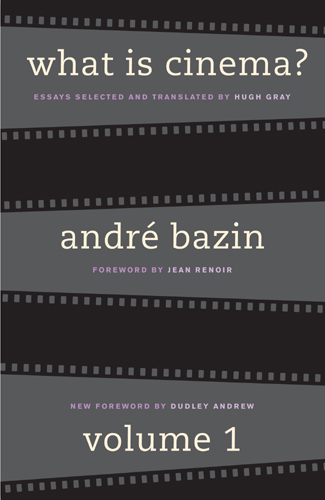

WHAT IS CINEMA?

VOL. I

by ANDR BAZIN

foreword

by JEAN RENOIR

new foreword

by DUDLEY ANDREW

essays selected and translated

by HUGH GRAY

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

Berkeley Los Angeles London

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, LTD.

London, England

1967, 2005 by the Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bazin, Andr.

What Is Cinema? / by Andr Bazin,

with a foreword by Jean Renoir,

with a new foreword by Dudley Andrew,

essays selected and translated by Hugh Gray

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-520-24227-0 (v. 1 : alk. paper)

e-ISBN 9780520931251

1. Motion pictures. I. Title.

PN1994.B3513 2005

791.43dc22 2004049843

FOREWORD

by Jean Renoir

IN THE DAYS when kings were kings, when they washed the feet ofthe poor and, by the simple act of passing by, healed those afflictedwith scrofula, there were poets to confirm their belief in their greatness.Not infrequently the singer was greater than the object of hissinging. This is where Bazin stands vis--vis the cinema. But thatpart of the story has to do only with what lies ahead. What is goingon now is simply the assembling of materials. Civilization is but asieve through the holes of which there passes the discard. The goodremains. I am convinced that in Villons day poets abounded onthe banks of the Seine. Where are they now? Who were they? Noone knows. But Villon is there still, large as life.

Our children and our grandchildren will have an invaluablesource of help in sorting through the remains of the past. They willhave Bazin alongside them. For that king of our time, the cinema,has likewise its poet. A modest fellow, sickly, slowly and prematurelydying, he it was who gave the patent of royalty to the cinema just asthe poets of the past had crowned their kings. That king on whosebrow he has placed a crown of glory is all the greater for havingbeen stripped by him of the falsely glittering robes that hamperedits progress. It is, thanks to him, a royal personage rendered healthy,cleansed of its parasites, fined downa king of qualitythat ourgrandchildren will delight to come upon. And in that same momentthey will also discover its poet. They will discover Andr Bazin,discover too, as I have discovered, that only too often, the singerhas once more risen above the object of his song.

There is no doubt about the influence that Bazin will have inthe years to come. His writings will survive even if the cinema doesnot. Perhaps future generations will only know of its existencethrough his writings. Men will try to imagine a screen, with horsesgalloping across it, a close-up of a beautiful star, or the rolling eyeof a dying hero, and each will interpret these things in his own way.But they will all agree on one thing, namely, the high quality ofWhat is Cinema? This will be true even should these pagessavedfrom the wreckagespeak to us only of an art that is gone, just asarchaeological remains bring to light the objects of cults that we areincapable any longer of imagining.

There is, then, no doubt as to Bazins influence on the future. Letme say however that it is for his influence on his contemporaries thatI hold him so deep in my affections. He made us feel that ourtrade was a noble one much in the same way that the saints of oldpersuaded the slave of the value of his humanity.

It is our good fortune to have Hugh Gray as the translator ofthese essays. It was a difficult task. Hugh Gray solved the problemby allowing himself to become immersed in Bazinsomething thatcalled for considerable strength of personality. Luckily alike for thetranslator, for the author, and for us, Bazin and Gray belong to thesame spiritual family. Through the pages that follow they invite us,too, to become its adopted children.

CONTENTS

Le Journal dun cur de campagne and the

Stylistics of Robert Bresson

FOREWORD TO THE 2004 EDITION

By Dudley Andrew

I.

IN THE TOUCHING foreword with which Jean Renoir graced thistranslation of What is Cinema? thirty-five years ago, he conjures upcivilizations murky past and its murkier future. When history has hadits devastating way, he writeswhen noisy people, problems, andevents have eroded and passed through the sieve of memory intooblivionthere will still remain those rock-hard formulations of greatpoets, which outlast even the subjects that occasioned their verse.Bazins essays are such gems.

Bazin is indeed cinemas poet laureate, or better, its griot. Full ofpraise poems and aphorisms, his essays emblazon cinemas historyand its possibilities in lapidary language that remains unmatched inboth precision and luminescence. Yet Bazin would have laughed at thisprecious gemological metaphor, as his Preface to Quest-ce que lecinma? makes clear. The bulk of what he had produced came out innewspapers and pamphlets, he said, useful mainly to fuel the fireplace.The history of criticism being already such a minor thing, that of aparticular critic ought to interest no one, certainly not the critic himselfexcept as an exercise in humility. Yet in the last year of his lifehe sifted through the nearly three thousand items he had written forpublication in order to find those key pieces (sixty-five of them) thatsignaled something larger than the particular exigency under whichthey were penned. Each selection addresses the question whichinhomage to Sartres great essay on literaturehe posed as title to hisfour-part collection: What is Cinema?

Was it this presumptuous title that tempted Glen Gosling, an editorat the University of California Press, to envisage an English translationof Bazin? He had been looking to follow up Rudolf ArnheimsFilm as Art, which he had brought out in 1957. Gosling worked out ofthe Los Angeles office, where he often ran into Hugh Gray, who wason Film Quarterlys editorial staff. Gray had been a scriptwriter in bothEngland and America before he began teaching aesthetics at UCLA, aposition that included service with Film Quarterly. It was his knowledgeof Bazins writings and of Bazins reputation in France that ledto the project. A generation older than Bazin, Gray nevertheless sharedhis philosophical orientation, evident in the theological defense hemakes in his introduction. An elegant conversationalist and stylist, hewas sensitive to Bazins clever prose, which he strove to deliver ingraceful English.

Its not clear how much of Bazins original Gray proposed toinclude, but Gosling surely meant to keep the volume sleek, restricting itmainly to articles dealing with films familiar to Americans. They settledon ten essays taken from the twenty-five that make up the firsttwo of the four volumes Bazin had laid out. After surprisingly goodsales, Gray was encouraged by Ernest Callenbach to prepare What isCinema? Volume II, sixteen more pieces selected from the forty thatcomprise the last two volumes of the original French. While any excisionmay seem sacrilegious, Bazins French publishers would in factcut nearly the same amount when they brought out their single volumedition dfinitive in 1981.

His modesty notwithstanding, Bazin might well have bristled atthis streamlining. In his own short preface he justified the inclusion ofbrief pieces on forgotten short subjects (like Death Every Afternoonand Gide) which Gray found expendable and are no longer to befound in the French collection. He claimed they serve as supportingstones to help bear the weighty theoretical edifice. Nor did he want tofold them into one of the longer essays (though Evolution of the Languageof Cinema, The Virtues and Limitations of Montage, andCinema and Painting are indeed compilations). The idiosyncrasiesand imperfections of some of the essays, he felt, are what give themcharacter and, as is the case with concrete, a certain tensile strength.Here Bazin gives away his secret: he regards his own essays the wayhe feels a critic should treat films, elaborating their lofty narrative andthematic problems, yet attending sympathetically to the contingenciesand impurities that made them fitting expressions in their historicalmoment. As a medium, cinema begs exactly such double vision: thenature of photography ties cinemas huge ambitions to historical andmaterial circumstances. Thus cinema shaped not only Bazins thoughtabout his vocation but also his very manner of thinking.