Auguet - Cruelty and Civilization

Here you can read online Auguet - Cruelty and Civilization full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Taylor & Francis (CAM), genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

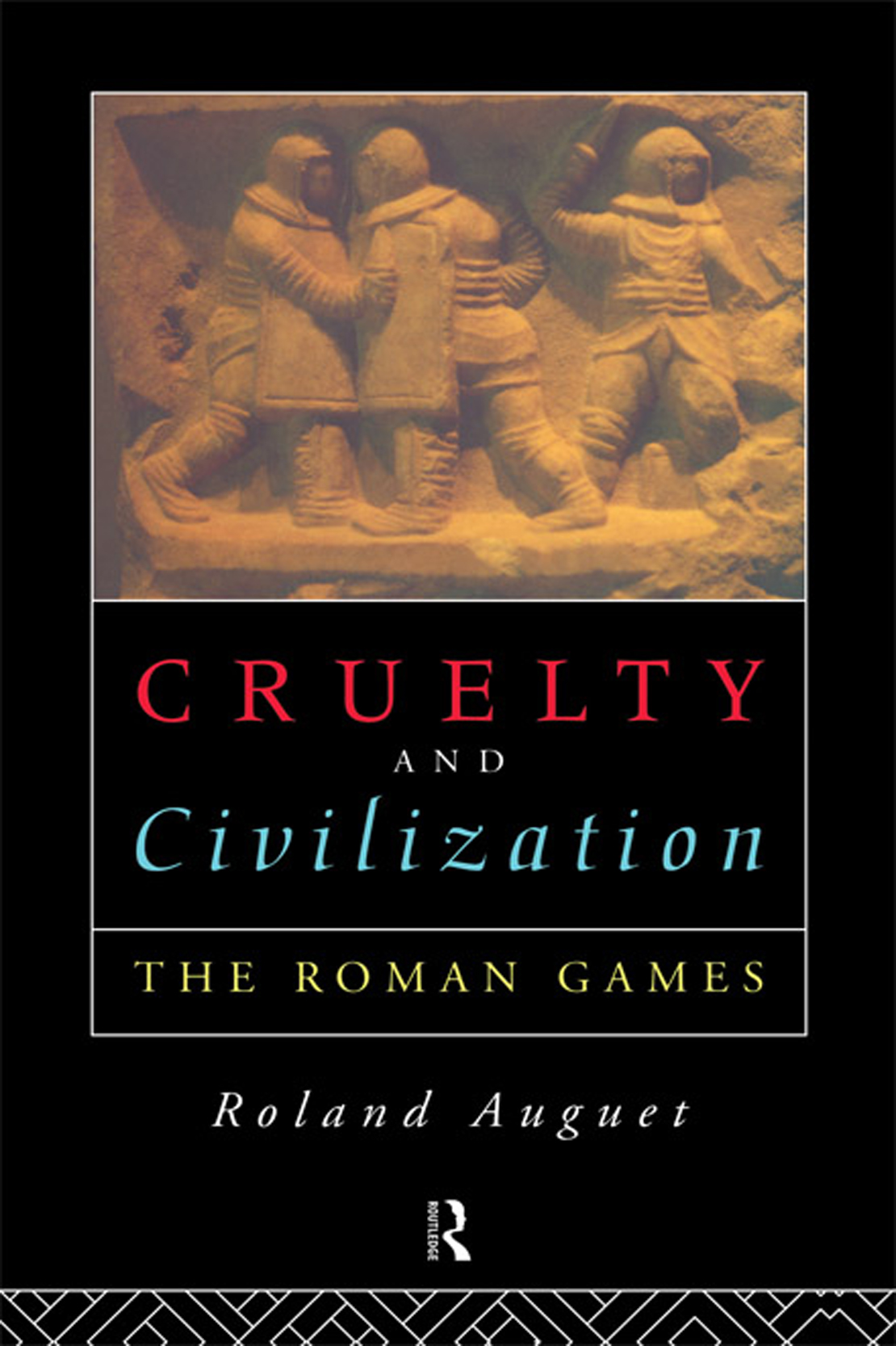

- Book:Cruelty and Civilization

- Author:

- Publisher:Taylor & Francis (CAM)

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cruelty and Civilization: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Cruelty and Civilization" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Cruelty and Civilization — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Cruelty and Civilization" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The great spectacles of Ancient Rome were not merely casual entertainment, a matter of choice for the audience, like the modern theatre. Under the Empire, the games became a public opiate and gave the daily life of Rome its rhythm and lustre. From one year to the next, the Roman citizens lived in anticipation of the games; they provided excitement and helped the citizens forget the mediocrity of their own condition and their lack of political power.

Roland Auguet has not restricted himself to the detailed reconstruction of these spectacles, he has also analysed the emotions of the crowd and the motives of the rulers. He explains why the games were so important in the life of the city and what the popularity of these spectacles, this strange combination of Cruelty and Civilization, reveals about the mentality of ancient Rome.

The Roman Games

Roland Auguet

London and New York

First published in 1972 by

George Allen & Unwin Ltd

Translated from the French

Cruaut et Civilization: Les Jeux Romains

(Flammarion, Paris, 1970)

Hardback reprinted and first paperback edition published in 1994

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

1972 George Allen & Unwin Ltd

1994 Routledge

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or

reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic,

mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter

invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any

information storage or retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Applied for

ISBN 0-415-10452-1 0-415-10453-X (pbk)

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint

but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

Of all the monuments left to us by the Romans the amphitheatres are the most imposing and undoubtedly the best known to the public, perhaps because some of them are still to be seen almost intact, like those at Nmes and at Aries. Everyone knows, too, the sort of spectaclesorganized shame, as historians have often stressedwhich took place behind these arcades to which the Roman architects gave such a grandiose nobility.

No general study of this immense subject exists. It is a subject which involves the history of Rome and of the Roman Empire, its monumental art and its sociology; it embraces one of the most important features of the daily life of the masses and of the ruler. Naturally, within the modest limits accorded us, we have not been able to be exhaustive. We must make a choice and reject many episodes which are often relevant to the history of the games. Thus, to take one example, it is not possible to speak of the votive games without entering at great length and in the most complex detail into the political and religious problems peculiar to a given period.

We have therefore been forced to proceed by suggestive touches, with the aim of giving the reader, by a study of the spectacles, a true feeling of the city and its masses, of a civilization, and of an empire.

Finally, the abundance of the bibliography to which we have had to refer (which often means reference to articles difficult to trace) has not permitted us to give detailed references on every page. This would have forced us to overload the text of the book which, moreover, has no pretensions to erudition. We have had to content ourselves with indicating references to the most important sources in the text.

Which of us does not recall the horrified fascination we felt as children when looking at those pictures in our school-books which came between the lowly dwellings of our ancestors the Gauls and the picturesque escarpments on which the first keeps of the Middle Ages were built? A gladiator, with movements clumsy and stiff because of his armour, half kneels and raises his hooked vizor, pierced by mysterious holes, towards an imaginary grandstand, menacing with his curved sword the man prostrate at his feet. His calm, the restraint of his gestures, his indifference, are among the things which particularly excite childish wonder. In another picture a lioness leaps upon a condemned man whose almost transparent robe still flutters on the sand; farther on, some vague figures crowd together at the approach of another wild beast; or perhaps the beast crouches, satiated, its paws doubled up over a shapeless mass, aloof and sullenly watching the dense throng of onlookers.

In one sense these pictures, a little morbid and shocking, teach us a lesson: that the life of a man has not always had the value that our own morality strives to give it. In the past it could be a mere episode, and death the instrument of a collective pleasure. But to the Why? which a discovery of this sort usually suggests, the caption below the picture affords no answer. These scenes impress themselves on us because they are monstrous and inexplicable. Their apparent pointlessness incites us little by little to attribute the violence which they reveal to some cruelty in the Roman nature, a prejudice which even closer contact with the ancient world may only correct with difficulty.

There is nothing more incompatible with the Roman mentality than the form of cruelty known as sadism, without which, however, it is hard to explain the continuance and success of certain of these games which have retained so sinister a renown. To a great extent cruelty of this type is pointless; it destroys and consumes without advantage, to satisfy a passion or merely for pleasure. It is a luxury. But the Roman was not only a realist; he was a slave to utility in the narrowest sense. The sacrifice of what could be a source of wealth, made to satisfy a momentary instinct, a partiality or a purely subjective emotion, was for him a serious fault, a slur on the most elementary principle of his morality. That was true in small things as in large; there existed, for example, a whole series of laws aimed at prohibiting the squandering of wealth caused by burning or burying with the dead articles which had belonged to them in life. No Roman would have had his wife and his horse buried with him, like the Great Khanthere would only be small personal objects or household pets such as cats or birds. Even more forcibly, the law prohibited drenching the pyre with costly perfumes or placing gold in the coffin, with the exception, formally specified, of what the dead man might hold in his mouth.

Just as they did not tolerate the wastefulness of grief, the Romans did not surrender to the demands of vengeance. As a rule they treated the vanquished with a generosity based on calculation; they thus avoided kindling a latent desire for revenge and preserved a territory which had become for them a capital gain. Annihilation and pitiless massacre were only a last resort against an irreconcilable enemy, such as Carthage or certain Breton tribes which were exterminated en masse

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Cruelty and Civilization»

Look at similar books to Cruelty and Civilization. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Cruelty and Civilization and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.