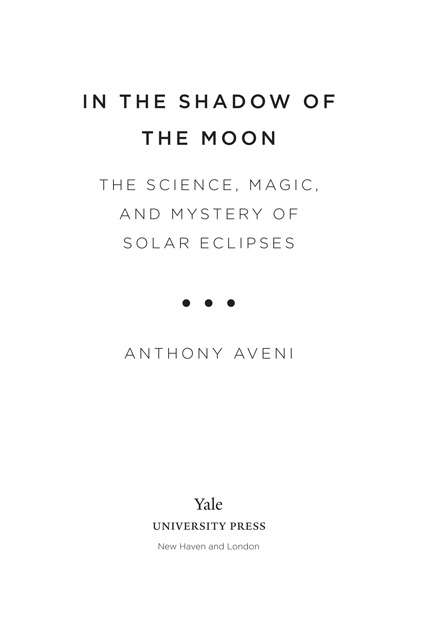

In the Shadow of the Moon

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of

Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2017 by Anthony Aveni.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including

illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107

and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public

press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Gotham and Adobe Garamond type by IDS Infotech, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016953812

ISBN 978-0-300-22319-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Ed Maxwellwise thinker, new friend

Contents

Preface

Trained in the sciences, I was once too engrossed in my specialty, the astrophysics of star formation, to think much about how different cultures might interpret the cosmos. Then I took a group of students to Mexico to measure the celestial orientation of pyramids at Teotihuacan and Chichn Itz.

By chance, I read reports in the literature about suspected astronomical alignments in sacred architecture, especially among cultures like the ancient Maya of Yucatn, and I had developed a method of precise surveying using celestial referents that caught the eyes of archaeologists. They invited me to try my techniques, and in return they taught me about the ancient peoples who watched the sky. We created a new interdisciplinary field variously called astroarchaeology, archaeoastronomy, and later (and less intimidatingly) cultural astronomy.

This fieldwork at the ancient Maya ruins in the rain forests of Central America opened my eyes to a sophisticated culture skilled in mathematics, writing, and the precise observation of nature. Our most recent work on the decipherment of a text written on a wall at the recently excavated city of Xultun in the Guatemalan rainforest proves that Maya astronomers, motivated by interests quite different from what we call science, were capable of predicting eclipses hundreds of years in advance, with minimal technology.

Modern astronomers questions about their ancient predecessors focus largely on aspects of the things in the sky: Did they mark sunrises and sunsets? What did they observe about the moon besides its phases? Did they predict eclipses? Did they know the world was round, that the sun is the center of the solar system, that were part of the Milky Way Galaxy in an expanding universe filled with galaxies like it? In other words, how like us were they? You could pose the same question about extraterrestrials.

Once I began working with archaeologists and anthropologists, I got exposed to questions of a different sort: What does another cultures astronomy tell us about its peoples religion, their beliefs in an afterlife, the way they treat their dead? Did they practice astrology? To what end? Did the ability to predict what was about to happen in the sky over their city affect their politics? What was their concept of history? Did they believe in their cosmic myths? Such questions center around what the sky meant to them.

Cultural astronomers are more interested in what people believe about celestial happenings than the happenings themselves. Whether modern Western civilization might label these beliefs religious, astrological, superstitious, or nonscientific, understanding their perspective allowed me to hold up a mirror to my own acquired scientific view of nature as a world where things happen without regard to human affairs. I see my face in that mirror, set against a background of other faces. The minds behind them harbor alternative ways of finding meaning that make sense to them. Drawing constellations or star patterns, following the movement of planets across a zodiac, or being dazzled by a solar eclipseexperiencing the sky is not the same for everyone. As an astronomer and an anthropologist, I find most explanations about how people around the world understand natural phenomena a bit short-sighted. This book represents my attempt to broaden our collective vision. There is much to be learned, shared, and felt about the human condition from a deeper exploration of the natural world seen through diverse human eyes.

In the Shadow of the Moon is a personal narrative that tells as much about people who have watched eclipses as the eclipses themselves. I was motivated to craft this book for publication in 2017 because, after experiencing a ninety-nine-year eclipse drought, mainland North America is on the verge of witnessing two transcontinental total eclipses of the sun. The twin eclipses positioned just over the American horizon offer an ideal prompt. If two minutes of dramatic daytime darkness generated more than one hundred articles in the New York Times in January 1925, imagine the attention that will attend seven minutes of totality spread seven years apart in large swaths centered on the middle of North America between 2017 and 2024.

Ive been the fortunate witness of eight total eclipses of the sun, bringing me to diverse places ranging from Canada to the South Pacific, across Atlantic waters off the coast of Argentina, to the Egypt-Libya border and the middle of the Black Sea. Despite all this travel, Ive logged less than half an hour in the complete darkness of the shadow of the moon. This is far from record breaking, and any amount of time is never enough. If youve already witnessed a total solar eclipse, you know what I mean.

CONTACT ONE

An Introduction to Solar Eclipses

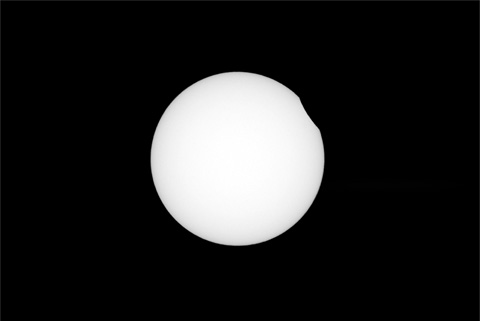

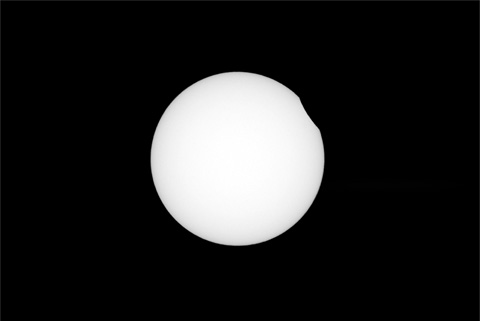

(Overleaf): Contact I / Begin Partial ( 2008 Fred Espenak, MrEclipse.com)

Colossal Celestial Spectacles

These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us: though the wisdom of nature can reason it thus and thus, yet nature finds itself scourged by the sequent effects. Love cools, friendship falls off, brothers divide: in cities, mutinies; in countries, discord; in palaces, treason; and the bond cracked between son and father. This villain of mine comes under the prediction; theres son against father: the king falls from bias of nature Tis strange!

William Shakespeare, King Lear, 1606

Studying the sky has made me realize what sheltered lives we lead. Efficient central heating and air conditioning signal our preference for being indoors. Most of us labor indoors, shop and dine indoors, work out and play tennis indoors. Our eyes spend most of their waking hours scanning computer and phone screens. We tan without exposing ourselves to the sun and, mindless of its daily course, we look instead at our watches to tell time and set appointments electronically. Think of the inconvenience the last time you experienced a power outage.

Living in such a world, we tend to dwell on the gains technology has afforded us: instant news, fresh food, the ability to move rapidly from place to place. But technology isnt the only reason we severed the links between daily life and the physical world around us. A change in the basic way we think about nature contributes to our detachment from it. The divorce from the world around us began five hundred years ago during the European Renaissance and continued through the late eighteenth-century Enlightenment, when nature was reintroduced to culture as a world apart from human affairs. Like the earth, the sky, once alive to our ancient ancestors, came to be regarded as inanimate matter, possessing neither soul nor meaning. Western society attempted to objectify the universe, making it an entity to be described and understood

Next page