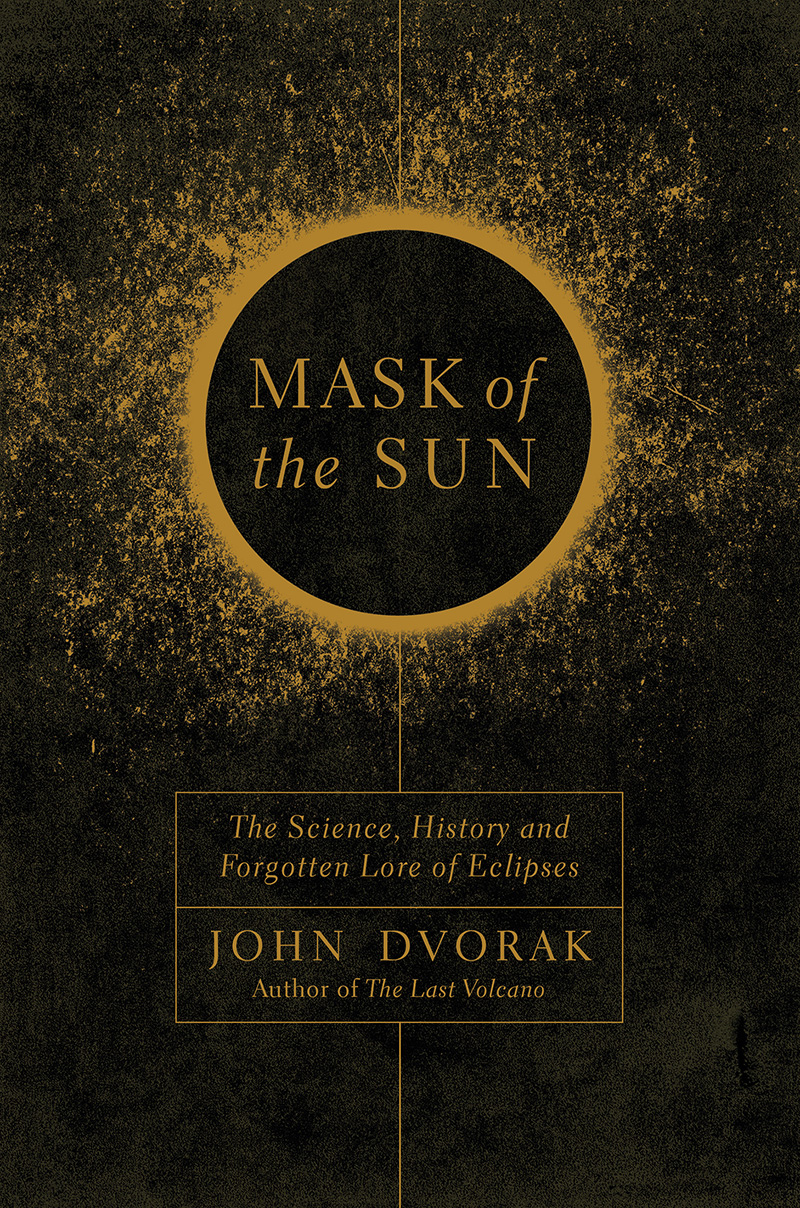

ALSO BY JOHN DVORAK

Earthquake Storms

The Last Volcano

MASK OF THE SUN

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright John Dvorak 2017

First Pegasus Books edition March 2017

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-330-8

ISBN: 978-1-68177-385-8 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

To Sarah and Joyce,

who continue to enlighten my life

Contents

Note to the Reader

In designating years I have used the increasingly more common B.C.E. (before the Common Era) and C.E. (Common Era) instead of B.C. (before Christ) and A.D. (anno Domini). Also, to be consistent throughout the book, all dates are given according to the Gregorian calendar that is used today throughout most of the world, and not the Julian calendar that was in use at different times in the western world. For example, in 1715, when Edmond Halley was publicizing the total solar eclipse that would be seen from London that year, he gave the date of the eclipse as April 22 because England was still using the Julian calendar. The date I use is eleven days later, May 3, 1715, the date of the same eclipse according to the Gregorian calendar.

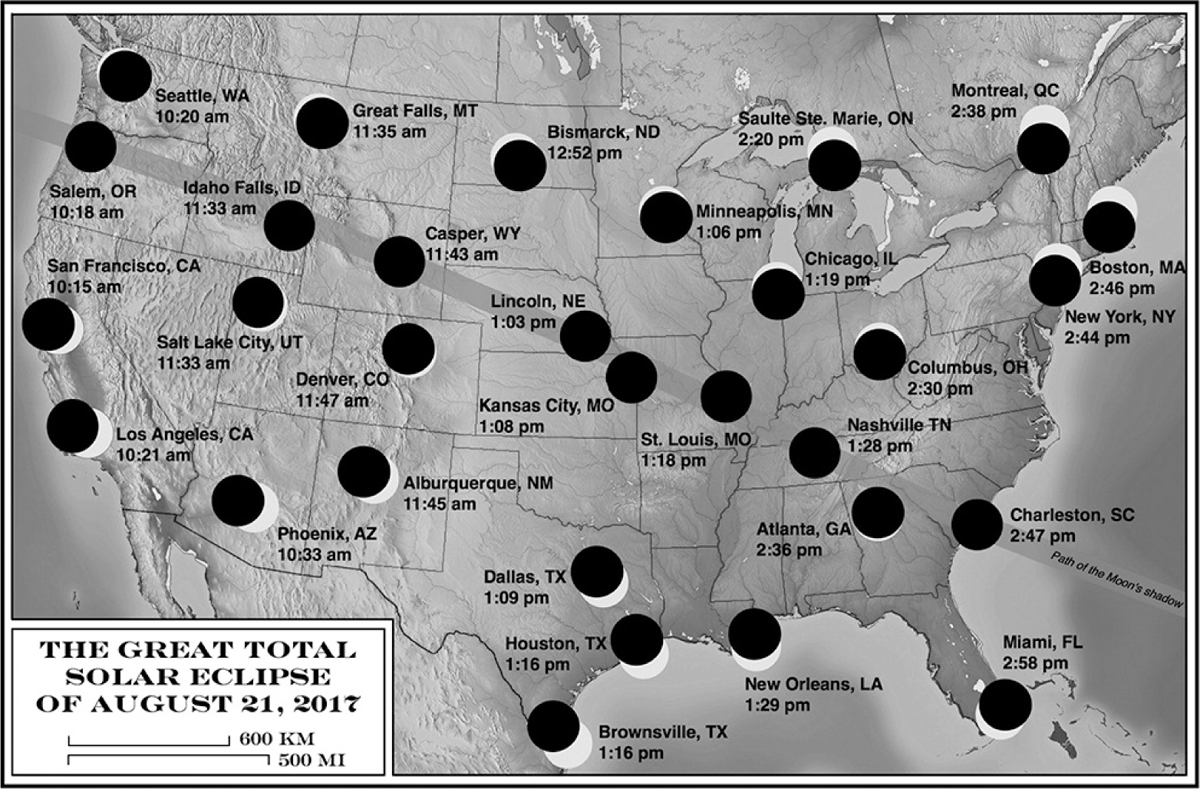

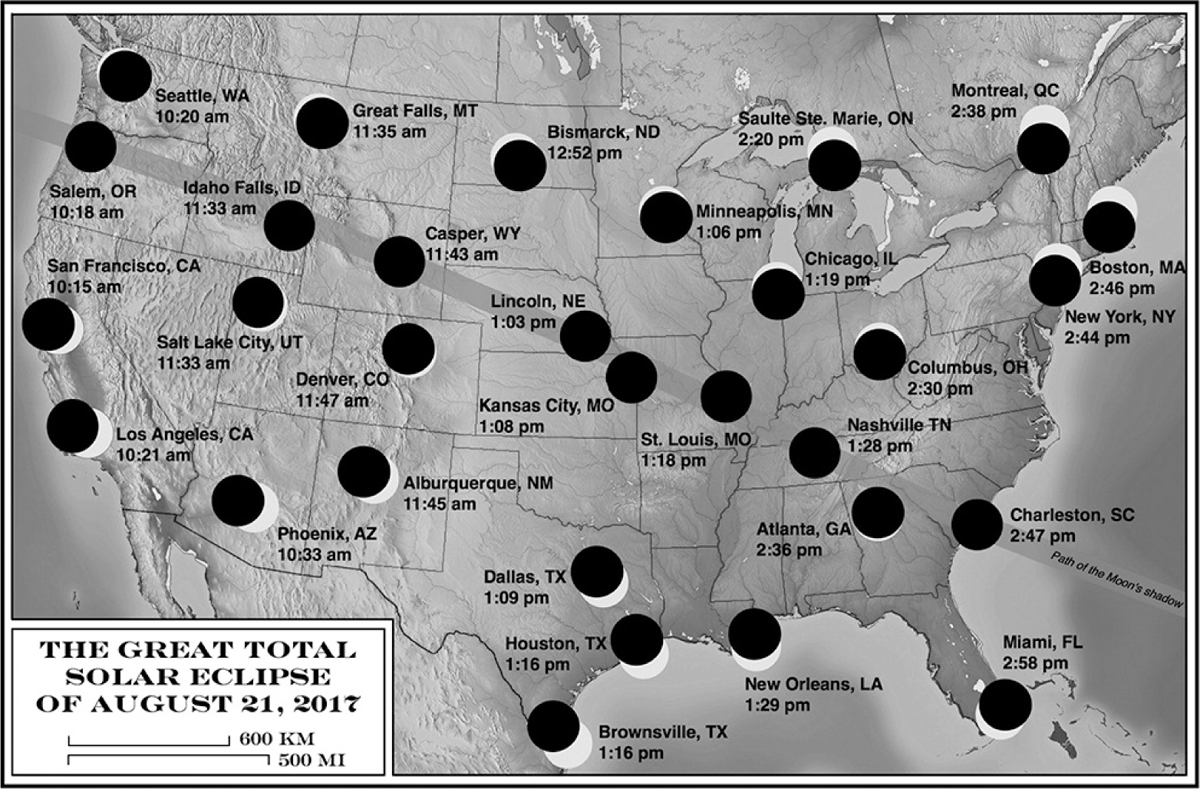

Path of the Moons shadow across the United States on August 21, 2017. The maximum amount the Sun will be obscured by the Moon is shown for selected cities. The time of maximum obscuration for each city is also given.

Show me the eclipse, we say to the eye;

let us see that strange spectacle again.

Virginia Woolf, after seeing a solar

eclipse from North Yorkshire,

England, June 29, 1927

Eclipses bepredicted

And Science bows them in

But do one face us suddenly

Jehovahs watchis wrong.

Emily Dickinson, 1862

I t was not clouds, but wind that was the concern.

For two days and nights, the giant dirigible Los Angeles had been kept inside a hangar to guard it from the violence of the wind outside, which blew crosswise, threatening to slam the Los Angeles against the doors if any attempt was made to emerge it.

The captain of this great airship, Navy Commander Jacob Klein, a veteran of the First World War, had skippered a destroyer that escorted troopships to France, routinely sailing through waters brimming with mines and menaced by German submarines. He had asked that a special weather forecaster be sent to the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey, where the Los Angeles was moored, to advise Klein when the weather might be improving, even slightly. As Klein knew, the Los Angeles would have to be launched before the next sunrise if he was to accomplish his latest assignment: to carry a dozen scientists aloft to observe a total solar eclipse.

Here it should be stated that the Los Angeles was a marvel of its age. It was the largest airship yet constructed. It consisted mainly of a giant airbag more than six hundred feet long and nearly a hundred feet high. A gondola hung on the underside with a command room in the bow and a large map room aft. In between were staterooms, rooms filled with bunks, two toilets, and a galley, so that up to four dozen people could be accommodated and comfortable onboard the Los Angeles . There was even a radio set so that those onboard the Los Angeles could keep in communication with those on the ground.

The giant airship had been built by the Zeppelin Company of Friedrichshafen, Germany, and given as part of the war reparations paid to the United States after the First World War as a condition of the Versailles Treaty. Its first official flight had been across the Atlantic Ocean in October 1924 when it was delivered to the Navy Air Station at Lakehurst. The second was a month later to Washington, D.C., where it received a christening from the Presidents wife, Grace Coolidge. The third, if weather permitted, would be to observe the total solar eclipse that would pass over the northeastern United States on January 24, 1925.

At 3:00 A.M. on the day of the eclipse, the weather forecaster woke Klein to tell him that there had been a noticeable drop in wind speed. The two men bundled themselves up and went outside. They stood there for almost an hour. The air temperature remained steady at a bone-chilling 5 Fahrenheit above zero. But the wind speed did drop from twenty to twelve miles an hour. That was enough. Klein decided he would launch the Los Angeles .

The forty men who would fly with him that day, which included eleven scientists from the United States Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., were awakened. Each man pulled on a heavy woolen shirt and woolen pants, an outer windproof jumpsuit designed for Arctic weather, a pair of wool-lined gloves, and a woolen cap with long flaps to protect the ears. When all were ready, the forty trudged outside, an onlooker thinking that they looked like a fat mans regiment. Then, in turn, each man boarded the Los Angeles , climbing the short flight of metal stairs that led from the hangar floor up into the gondola.

Three hundred sailors who were stationed at Lakehurst were also awakened. They donned warm clothing, though not as protective as that worn by those who would fly that day. The three hundred then gathered inside the hangar where they were divided into two groups. A group of seventy-five was ordered to stand around the outside of the gondola, each man grabbing hold of a handrail. Their purpose would be to lift the entire airship and walk it outside. The remaining two hundred and twenty-five men were divided into subgroups of fifteen men each. Each subgroup was assigned a rope that hung down from the airbag. Their purpose was to keep the ropes taut and hold the Los Angeles close to the ground until given a signal to let it go.

As soon as everyone was in position, Klein gave the order to rev, in turn, each of the five gasoline motors that would drive propellers that would pull the Los Angeles through the air. After the last motor was checked out, the commander ordered the giant doors of the hangar opened. A gust of wind immediately swirled around the inside of the hangar. The men holding the ropes strained and steadied the airship. Klein then gave the order for the men holding onto the handrails to lift the Los Angeles , but the giant airship would not move.

The extremely cold weather had negated the calculations that were normally done to determine how much helium was needed inside the airbag to allow the Los Angeles to fly. Not having enough time to add more helium, Klein ordered ten men off the airship, including two of the scientists.

Now the airship could be lifted, and the seventy-five men holding on to the handrails proceeded to carry it outside. As soon as the Los Angeles cleared the doors, a gust of wind caught it broadside. There were struggles with the ropes, the men who were holding on to them skidding across a frozen ground. The seventy-five standing outside the gondola holding on to handrails were lifted several feet into the air. Klein had the motors revved and the giant tailfins trimmed. Slowly the giant airship settled back to the ground.

Next page