ST. TERESA OF CALCUTTA

As a teenage boy, I was the gawky kid who dribbled a basketball off his leg, which is bad enough anywhere when youre fourteen years old. I happened to grow up in Indiana, one of the most basketball-crazy places in the world. So in freshman year of high school, I went out for the cross-country team. Through the farmlands and developing suburbs on the northwest side of Indianapolis, we would run five-mile loops along the flat ground around the school. At home I would pound across the rolling hills of my neighborhood. I could run and run. The challenge for me was starting on those hot, muggy mornings that are built into the Indiana summers. Once I got going, and found the right pace, I kept moving. Competitive sports were not for me, so I quit the team. But for years, I ran long distances. They are less about speed and more about time; staying with the run and covering the ground.

I write to you from midlife, fortunate to have survived a lethal disease that brought my running days to an end. But in my work as a criminal defense lawyer, I still cover long distances. Yes, some cases are sprints, or middle distances. Yet in others, getting to justice is a journey that spans decades. Once I get started, I keep going. It turns out that there is really no choice.

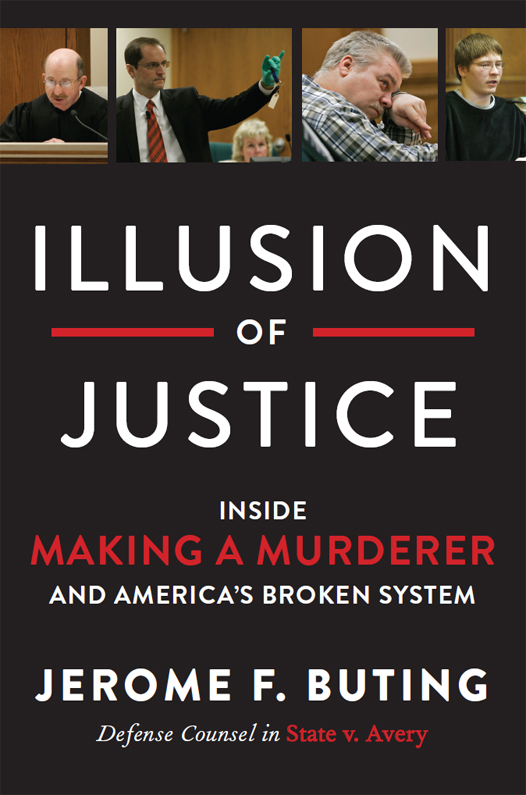

On a blustery Wednesday afternoon, Dean Strang and I met at his office in Madison, Wisconsin, for our first discussion about representing Steven Avery, the most famous innocent man in the states history. It was about 3:00 p.m., March 1, 2006.

At the very moment Dean and I started speaking, a new drama was coming to an end 135 miles away that we knew nothing about, but that would change everything. A sixteen-year-old boy was sitting on a couch in a room of the Manitowoc County Sheriffs Office. His moon face was hidden in his palms, which were pressed into his head. Seated next to him, the boys mother tried to wrench off the mask formed by his hands, but his fingers would not yield. Leaning forward, elbows on his legs, head in hands, he was bent into the position people are instructed to take during a plane crash. He had spent nearly the whole day with interrogators, offering grunts and yahs to one leading question after another. One of his longest utterances was to ask if he could get back for a class at 1:29 p.m., explaining, I have a project due in sixth hour.

A man spoke to the boys mother, assured in his tone. Weve been doing this job a long time, Barb, and we can tell when people are telling the truth.

The boys name was Brendan Dassey, and although his name was unfamiliar to Dean and me then, we would soon be finding out a lot more about him and what had happened that day.

While Brendan was seated, miserably, in Manitowoc, Dean and I spoke about my joining the defense of Steven Avery, who was accused of killing a woman at his familys auto salvage yard and burning her body. Dean had already been retained. For close to an hour, we had gone over practical matters like the division of labor; what had been learned by the public defenders who had been his lawyers when he was first arrested; the resources available from Avery to hire experts and investigators; and where the case stood. Up to that point, the charges seemed based on strictly circumstantial evidence.

Then the phone rang.

An Avery relative was calling. Deans end of the conversation, at the beginning, was mostly uh-huhs and yess, so I half listened and glanced around the office. On the walls, he had a few pieces of artwork depicting events in legal history, a scholarly interest of Deans. He also had a standing desk, which not too many people were using at that time. It caught my eye because Id had back problems a few years earlier. A trophy stood on a shelf, which I would later learn was for hurling. Hurling is an ancient Irish game, a tougher, more physical ancestor of field hockey. Dean didnt play, but a friend had given him the trophy as a present.

He and I were partners in different firms. We had worked together a few times, and I had high regard for his work and acumen. Dean wasnt part of the crowd that hung out in courthouse watering holes, but he was levelheaded and a relentless, hard-driving professional, quick on his feet. Also, he was hard not to like, which was important, because we were going to spend a lot of time together.

Now I could hear his side of the phone call take a turn.

Youve got to be kidding me, he was saying. Arrested? The nephew? For what?

At age forty-three, Steven Avery had already fallen once into the gulf between what is preached and what is practiced in Americas criminal justice system. It took him more than two decades to climb out and less than two years to fall back in.

Steven Avery had spent eighteen years in prison for a sexual assault he had nothing to do with before the real culprit was identified through DNA testing and Steven was unequivocally cleared. Now Avery was facing an even more serious charge: the murder of a young woman, Teresa Halbach, who had come to his familys auto salvage yard to take advertising photos for a trade magazine. In the story initially laid out by the authoritiesbefore there was a trial, before anyone outside law enforcement had looked at any of the evidenceAverys guilt was a foregone conclusion. Some of the victims burned remains were found near a garage used by Avery. His blood was in her car. Her car key had been discovered in his bedroom. But this tidy narrative of detective work grew messier as details emerged about the peculiar circumstances under which the supposedly incriminating evidence against Avery had been gathered. Some of the investigators were not even supposed to have been on the Avery property, or indeed have anything at all to do with the case, because they were connected in various ways to the frame-up that had sent Avery to prison two decades earlier. Once their involvement was revealed, public certainty about Averys guilt began to erode.

Even before this meeting with Dean, Id been following the story on television and in the newspaper, like many other people in the Wisconsin area. My connection to it was deeper than most. I had met Steven Avery. As it happened, Id served on the legislative task force that was set up to investigate what went wrong in his wrongful rape conviction, and to recommend reforms.

The Avery family ran its auto scrap yard in a place called Two Rivers, Wisconsin, which is just about halfway between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, not exactly the middle of the United States. But its not far off. About a hundred miles north of Milwaukee and ten miles west of Lake Michigan, the scrap yard is in an area remote enough for a family of modest means to own forty-four acres of land. On it they stored thousands of cars, an inventory of discards that could be sold for scrap or parts. Family members lived in trailers or homes near the yard. It was a business, and it was a life. Not quite a true city, not a suburb, Two Rivers is a world apart, and the Averys lived on its outskirts. And it is in such forgotten places, among people from the wrong end of town or no town at all, that the ideals of our criminal justice system are stress-tested every day.

On that early March afternoon in 2006, no one would have expected that scrap yard, and the people living around it, to set off one of the most far-reaching discussions about American criminal justice for generations. That millions of people would become absorbed by the Avery case a decade later was, at that moment, beyond conception. Improbably, it became the subject of a ten-hour, ten-episode television documentary,