The project is Hughs idea. He sends me an email: I hope you can see all the trouble your writing has caused.

He wants to publish the stories Ive been calling The Paradise Project. The pieces are slight. Whimsical. I dont know where they come from, and I dont ask.

Im touched that these stories have got their hooks into Hugh, although I dont quite believe it. I feel like a teenager invited to a party by the most popular boy in class, a boy who cant possibly like me. I suspect a mistake. Or worse, a trick.

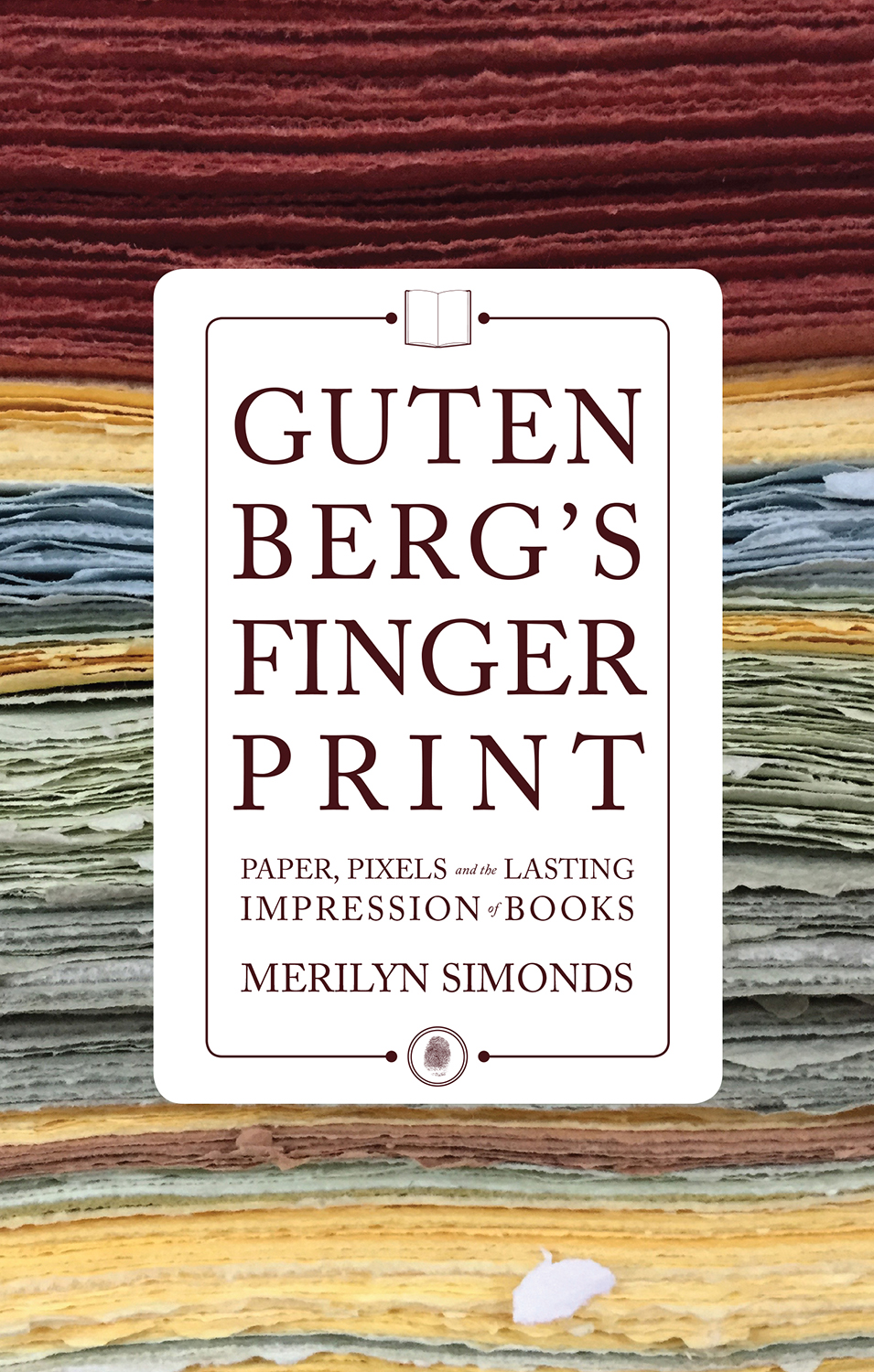

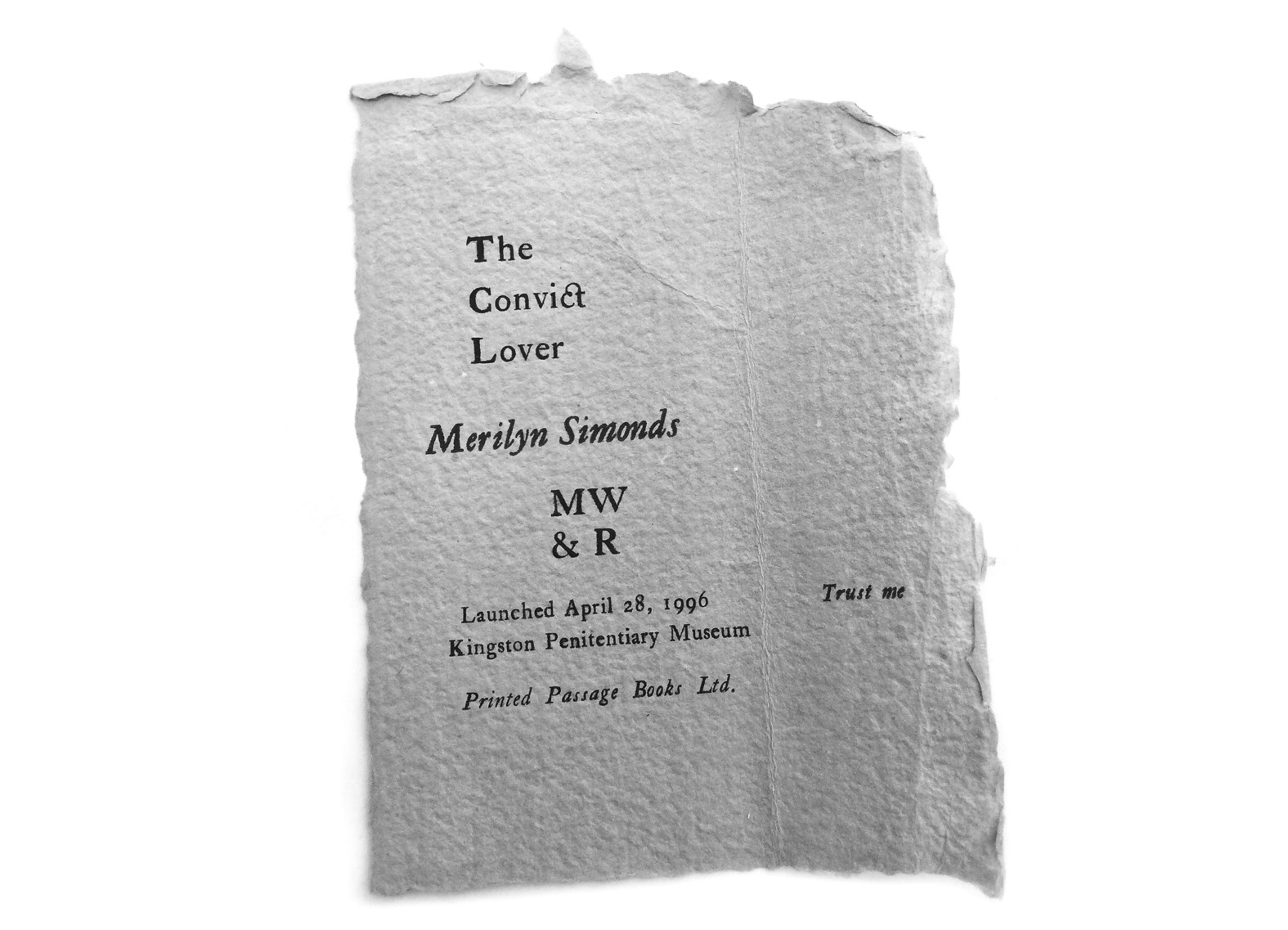

Hugh Barclay introduced himself to me more than a dozen years ago, which sounds very civilized, a calling card on a silver salver. Not the correct impression at all. He showed up at my book launch for The Convict Lover, which took place in the Penitentiary Museum that occupies the old Wardens House across the road from Kingston Penitentiary, then home to sex offenders and stool pigeons. Canadas Alcatraz, although the architects clearly forgot that Lake Ontario freezes over in winter, a slippery expressway to the United States for anyone who could scale the high stone walls.

On the day of the launch, the museum is packed. The entire village of Portsmouth has turned out, it seems, and half of Kingston, too. During the eight years of writing The Convict Lover, I was convinced no one would want to read it. The story was too old-fashioned. Too odd. But here I am, standing at a limestone plinth chiselled by convicts, signing book after book, the room crowded with people bursting with stories of their own: the old man who had a convict as a nanny before he went to school (his father was chief keeper); a woman who, as a girl, passed peaches to the convicts as they marched through the village on their way to the quarry to break stone. The lineup is so long and discombobulating that when my sister hands me her book, I pause over the page, simulating a cough, as I try to remember her name.

I notice Hugh right away. Or rather, I notice his black beret. Hes shortsomething peculiar about the curve of his spinebut his rakish beret keeps bobbing into view until it is right beside me.

Here! he says, shoving a green bookmark under my nose. Im Hugh Barclay! This is my wife, Verla! The man doesnt speak, he proclaims.

We made this! Hugh taps the length of thick paper. It is the colour of mashed peas. We have a printing press. Thee Hellbox Press.

I make noises of gratitude and prepare to add the bookmark to the stack of photos and mementoes others have given me.

You see. You see, he says, tugging the bookmark back to the centre of the plinth, tapping it more insistently now. You see? The C and T at the end of Convict? The bit that connects them? Thats called a ligature. We chose the type especially. Its like the letters are handcuffed together.

He is chuckling. So is Verla. They both stare up at me, delighted. Expectant. I look again, more intently, at the bookmark.

Verlas wheelchair has cleared a space like a stage around the three of us. The room and the milling crowd fall away, and it is just the three of us, gazing down at this unexpected chunk of raw, ragged paper, visibly dented with words, letters joined by a curving line defined by a term Ive never heard before.

Amazing, I say. And before I know it, Im chuckling, too.

Hugh is a fixture about town. His beret, tilted at a dapper angle, can be seen at every literary gathering: book launches, readings, festival performances. Hes almost always pushing Verlas chair. And then he isnt.

Hugh is not young, although I cant guess his age. Over sixty. Under eighty. His body is misshapen, as if wracked by some extended, torturing condition, yet there is something child-like about his face. Not innocence: the wisdom in his eyes is hard-earned. Delight, yes. Wonder, perhaps. Optimism, for sure. Its his enthusiasm, I decide, that makes him seem so young. A frank and forthright zeal that cares nothing for propriety or convention, the accepted rules of adult intercourse.

I find myself watching for him at public events, edging over for a chat, craving a shot of his fervour, his wit unstained by irony, unmarred by the faintest glint of condescension or cruelty.

You know, dont you, that you havent really made it until youve been published by Thee Hellbox Press, he says to me at a gathering of the Kingston Arts & Letters Club. My husband, Wayne, and I have just presented a talk on the art of collaboration, based on our experience writing a travel memoir together, Breakfast at the Exit Caf.

You should send me something, Hugh says.

I dont have anything. Its a bit of a lie. Im not a prolific writer, and its true that I dont have stacks of unpublished manuscripts stuffed in a bottom drawer. But I do have a thin pile of stories, stories I cant yet imagine releasing to the world.

The Convict Lover was my first literary book. Over the next fifteen years, I launched six more: a book of stories, a novel, a travel memoir, a book of essays, two anthologies. When Hugh sent me that email calling me a troublemaker, I was working on another novel, a long, slow exploration of solitude and refuge. From time to time, as I wrote the novel, bizarre short fictions would flash onto the page. The same thing happened when I wrote The Convict Lover, stories that I eventually gathered up and published as The Lion in the Room Next Door.

These new stories are different. Shorter. Stranger. Leftovers, of a sort. Like remnants of a dream that interrupts my consciousness long after I stir awake. For years, I had been writing about my garden. Not just my garden: gardens. My novel The Holding began as an exploration of the nature of control and the control of nature. When Alyson and Margaret work their plots, are they trying to make nature do what they want, or are they trying to sidle up closer to it, bring it into their too-concrete lives? A New Leaf carried on that conversation within the borders of my own gardens at The Leaf, the patch of woods and cleared land where we lived in Eastern Ontario. It was a gardener, I came to realize, who changed the course of human history, plucking a seed and planting it where she wanted it to grow instead of where it randomly fell. A gardener who made farming possible, and cities, and trips to the moon.

Neither the novel nor the essays contained anything like the lyric fantasies that were erupting now. I had never written anything like them. When I was writer-in-residence at the University of British Columbia, I tacked a few to the end of a reading.

I dont know what these are, I said by way of introduction.

Theyre poems, a friend said afterwards. She is a poet and a teacher; she brought her entire class to the reading. The students vigorously nodded their heads.

![Robert Hugh Benson [Benson - Robert Hugh Benson Collection [11 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/139831/thumbs/robert-hugh-benson-benson-robert-hugh-benson.jpg)