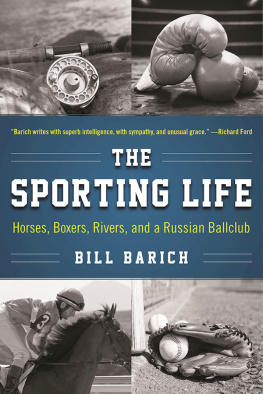

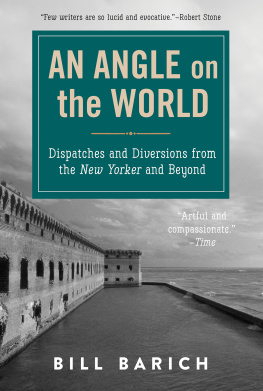

ALSO BY BILL BARICH

FICTION

Carson Valley

Hard to Be Good: Stories

NONFICTION

Long Way Home

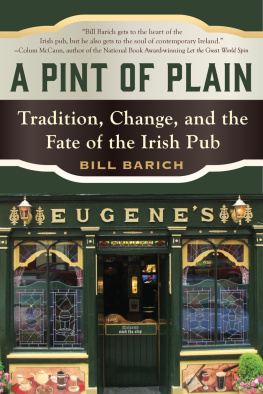

A Pint of Plain

A Fine Place to Daydream

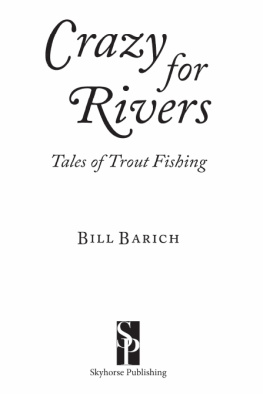

Crazy for Rivers

Big Dreams: Into the Heart of California

Traveling Light

Laughing in the Hills

Contents

Preface

M Y FASCINATION with the sporting life began when I was growing up in a desolate Long Island suburb, where children were expected to amuse themselves at the playground or on the sandlot fields. As a boy, I indulged in endless rounds of baseball, basketball, and football, with games of stickball, stoopball, punchball, and Wiffle ball tossed in for good measure. I fished a little, as well, and tried boxing a few times, but the brief joy I felt in the ring vanished abruptly when a much tougher kid knocked me to the canvas (bloody nose, loose tooth) in a Police Athletic League bout. My future lay elsewhere, I decided right then, and I never donned the gloves again.

Horses came into the picture later, when I was a sophomore in high school and itching for some minor-league trouble. Our town was close to Roosevelt Raceway, where the not entirely wholesome sport of harness racing is featured, and because some neighbors on my block viewed the track as a symbol of degeneracy, I was eager to slip through the turnstiles at the earliest opportunity. But before I could pull it off, I became a junior gambler with the help of my friend Eddie Greco, who was older than me and already had a job in the real world that put him in touch with the action.

Eddie worked the restaurant counter at a bowling alley near Roosevelt, where the menu was long on burgers and doughnuts. Included among his customers were a few sulky drivers, who popped into the lounge for drinks, ordered some food, and tipped my pal with betting advice instead of money. The horses they touted ran remarkably well. I learned about the scam when I bumped into Eddie at a Friday-night party. He mentioned that the guys had just alerted him to Rhythm Lad, a hot pacer scheduled to run on Saturday.

Ive got him across-the-board, he bragged.

How much does it cost? I asked, never having heard the words across-the-board before.

Six bucks.

I dipped into my wallet. On Sunday morning, I nearly jumped out of my skin when a copy of Newsday , our local paper, thumped against the front door. There in the black type of the racing charts I saw Rhythm Lad on top, paying eighteen dollars for the six Id invested. Naturally, I was keen to collect my winnings, so I called Eddie at the bowling alley around noon. But he let me down by saying hed already parlayed the money on a second hot horse about to run. Parlay was another new word I added to my vocabulary.

In about a month, I had seventy-five dollars hidden in a shoe box in my bedroom closet. My lucky streak might never have quit, not with Eddie Greco at the helm, except that I got cold feet. My mother, a devout churchgoer, believed gambling was a sin, and if she caught me with the stash, I knew Id be in for a terrible punishmenthours of washing dishes or, worse, enforced Bible study. So I got rid of my bankroll by lavishing gifts on my girlfriend, squiring her around our best shopping mall with all the subtle cool of a mobster showing off his bimbo.

I did visit Roosevelt in person, finally, even though I wasnt old enough to place a legal bet. Nobody ever checked my ID when I bought a ticket, thoughonly when I tried to cash one. This created a strange scenario, whereby I had to wander through the crowd in search of an honest-looking adult who might assist me without demanding a cut of the profits. Sailors in uniform proved to be particularly sympathetic, just as they were whenever an underage teen needed an ally to score a six-pack at the corner deli.

Harness racing failed to move me, I must admit. The sight of grown men speeding by in their rickety sulkies was more comic than engaging. It wasnt until I took the train to Belmont Park and stood by the rail with my heart pumping that I got hooked on horses for real. I loved the sheer animal grace on display, the brightly colored silks and the beauty of the pageant. I noticed, too, how during the fleeting time of a race, I had no interest in anything beyond the moment. What Id discovered was a sort of release.

In rereading the pieces here, I can see that I still look to the sporting life for escape and maybe even transcendence, if that isnt too grand an idea. It can happen on a trout stream when I fall into the meditative grace of casting, or during the raw intensity of a good boxing match, or at a baseball game if enough is riding on the line. Its the electricity I crave, a bolt from the blue that burns the fuzz from my brain and reminds me that Im still alive and kicking.

I continue to follow the horses now and then, if only to see where theyll lead me. In every country, racing offers a vivid cross-section of the population and an instant introduction to the cultural norms. In Barbados, I once had to squeeze past a dreadlocked reggae band to place my wagers; in Florence, I enjoyed a wonderful meal of pasta and roast veal at a tavola caldo off the backstretch, where the patrons cared more about the food than the betting; in England I ate cockles and jabbered with Cockney bookies over the relative merits of steeplechasers; and in Louisiana, way down in the bayous, I watched in awe as some Cajun jockeys strolled into the paddock guzzling cans of beer.

Another great benefit of the sporting life is the amazing array of people you meet. Although I never shook hands with Mike Tyson, I did chew the fat with Donald Trump and attended his celebrity bash in Atlantic City, where, after Iron Mike disposed of Michael Spinks in ninety-one seconds, somebody picked my pocket. Pat Lawlor, an Irish pug from San Francisco, treated me as a member of his family, while Andrei Tzelikovsky of the Moscow Red Devils sold me a nesting doll and gave me a pack of Soviet baseball cards as a bonus.

In the end, I suppose this book is merely another aspect of my curiosity about the world and what we make of it. How we play is who we are, at least to some extent. If pressed, I might even argue for the importance of the pastimes we devise and the relief they sometimes deliver. The human being who invented the ball will never be as celebrated as the wheels inventor, but we should still value the contribution. I hope these stories reflect the pleasure I took in writing them, and convey it to the reader.

Chasers

I HAD NO INTENTION of playing the horses on a recent vacation trip to London. Instead, my pursuits were going to be cultural. From a Cockney broker, I rented an apartment on Belsize Avenue, in Hampstead, and spent my first few days touring the museums nearby. I saw the four-poster John Keats slept in, read the bad reviews of his second book, and marvelled at the elegance of his handwriting. Around the corner, I visited the house where Sigmund Freud lived for the last year of his life and learned from a tour guide that hed been fond of such writers as Twain, Poe, and Anatole France.

When I wasnt at museums, I was browsing in secondhand bookstores on Charing Cross Road, or going to galleries and attending concerts at the South Bank Centre. One Sunday afternoon, I heard a chamber group perform a spirited version of Schuberts Trout Quintet, and afterward, as I walked a path along the Thames, I found this poem inscribed on a paving stone: