by the same author

THE MIGHTY NIMROD

A Life of Frederick Courteney Selous

SHAKAS CHILDREN

A History of the Zulu People

LIVINGSTONES TRIBE

A Journey from Zanzibar to the Cape

THE CALIBAN SHORE

The Fate of the Grosvenor Castaways

STORM AND CONQUEST

The Battle for the Indian Ocean, 180810

COMMANDER

The Life and Exploits of Britains Greatest Frigate Captain

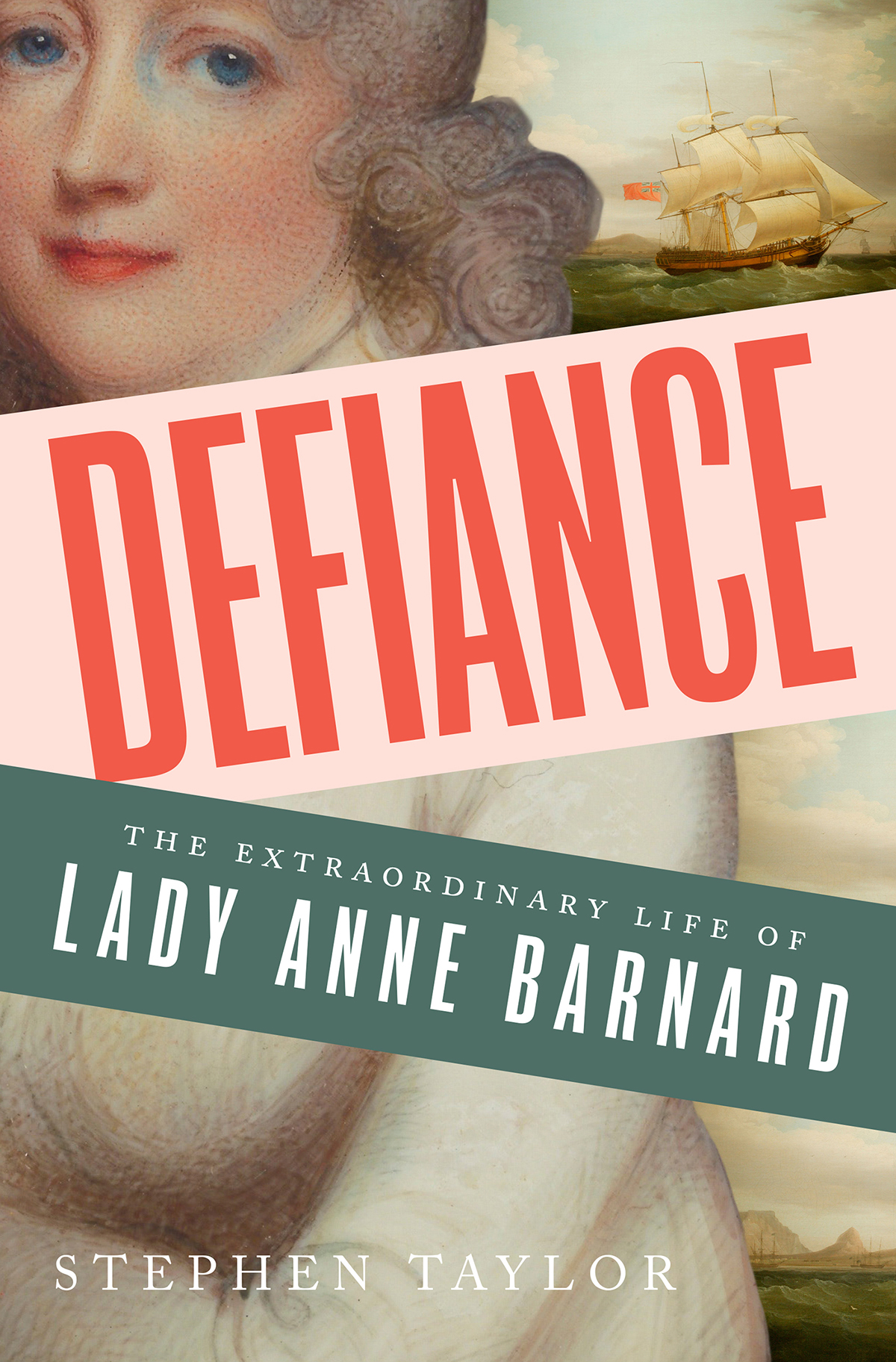

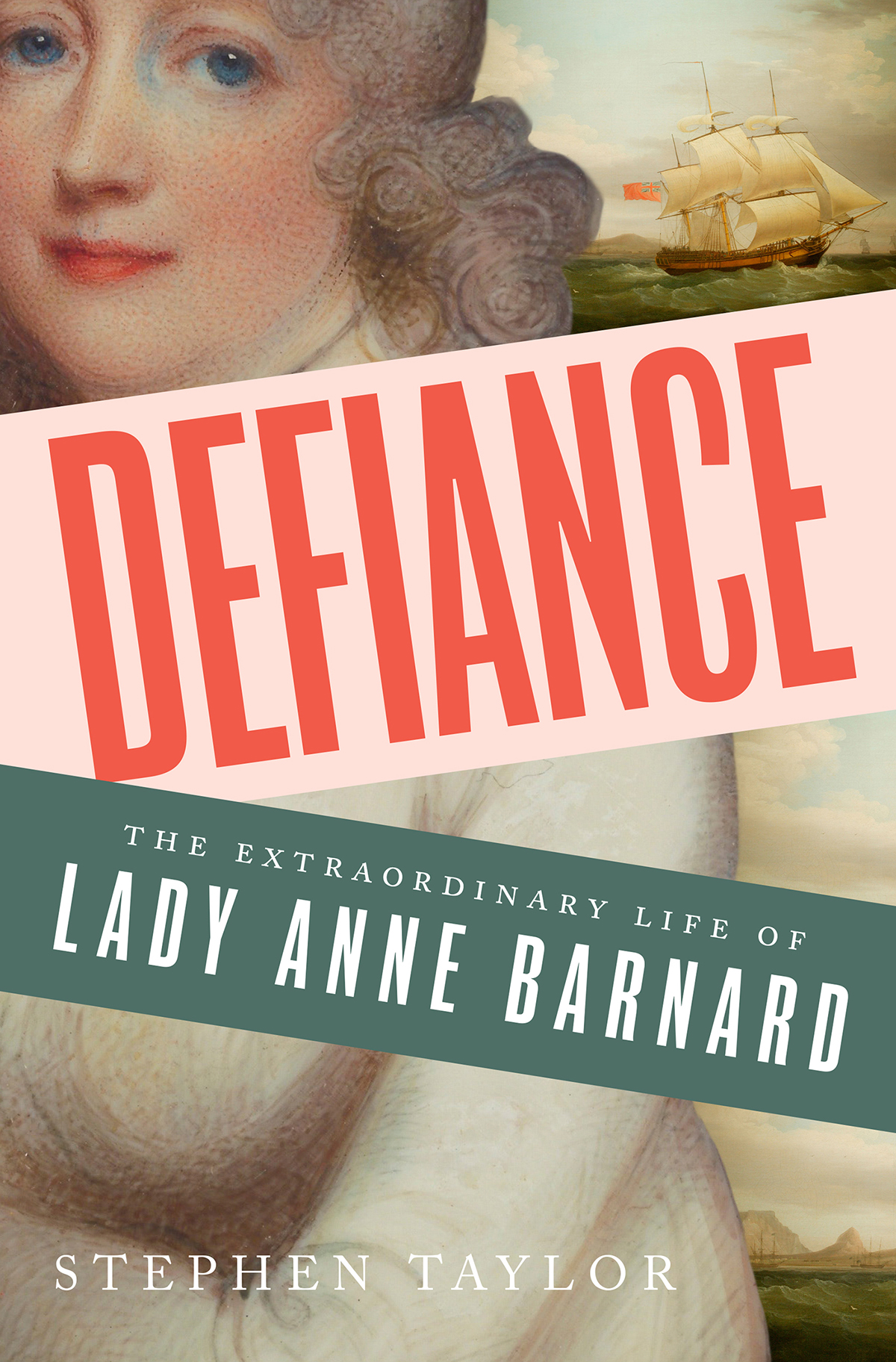

DEFIANCE

The Extraordinary Life

of Lady Anne Barnard

STEPHEN TAYLOR

Copyright 2016 by Stephen Taylor

First American Edition 2017

First published in Great Britain under the title Defiance: The Life and Choices of Lady Anne Barnard

All rights reserved

Jacket design by Linda Huang

Jacket art: Portrait Miniature of Lady Anne Barnard, Anne Mee (Mrs Joseph) (c. 17601851) / Private Collection / Photo Philip Mould Ltd, London / Bridgeman Images; (sailing ship) National Museum of Culture, Pretoria, South Africa / imageBROKER / Alamy Stock Photo

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

ISBN: 978-0-393-24817-3

ISBN 978-0-393-24818-0 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

To my daughter Juliette

Contents

Illustrations

IN TEXT

All drawings by Anne Barnard (reproduced with permission)

PLATES

Reproduced with permission

Private collection

Private collection

National Portrait Gallery, London

Iziko Museums of South Africa, Social History Collections

Private collection

National Portrait Gallery, London

National Portrait Gallery, London

National Portrait Gallery, London

Private collection

Courtesy Peter Barrett Philip Mould & Company

Courtesy Peter Barrett Philip Mould & Company

National Portrait Gallery, London

Reproduced with permission

Reproduced with permission

Reproduced with permission

Iziko Museums of South Africa, Social History Collections

Right to the last months of her life Lady Anne Barnard stayed tied to her desk in Londons Berkeley Square. Her stomach pain was acute and she knew as she scratched away to a much-loved nephew that her time was short: I am beginning to burn and put my papers in order, she wrote, but fear I shall not accomplish it.

Her misgivings were natural. Banked around her was one of the most formidable collections of papers compiled by any woman of letters of an age that counted Jane Austen and the indefatigable Fanny Burney among its number. Piled on shelves and in cabinets stood letters, journals, memoirs, diaries, poems, sketches and watercolours along with reams of what Anne called her scraps. Just what these amounted to before she started to cast them into the flames is unclear, but the task did indeed remain incomplete. The surviving papers still extend to something like a million words.

Soon after her death, her nephew returned to the old house. James Lindsay had lived at 21 Berkeley Square as a young guards officer before going off to war, then again while convalescing and, since Waterloo, whenever he was in London. Colonel Lindsay walked with a stick these days, the mark of his wounds, and entering the dark house, emptied of the society that once filled it with music and hilarity, brought on the sense of a past age. The long drawing room with its portraits by Gainsborough and Lawrence was shrouded by drawn curtains. Annes pianoforte stood silent. Her mounds of papers gathered dust.

James wandered upstairs, to the room he had occupied at what he used to call kind Aunt Barnards hotel. The nine bedrooms were rarely empty in those days, with guests who ranged from another dashing army officer one esteemed a hero by Wellington no less to a mysterious young girl of African origin whom Anne called my protge of a darker complexion. The circle of characters to be encountered downstairs was just as eclectic literary and artistic, political and royal; among Annes most intimate friends were Londons oddest couple, the Prince of Wales and his secret wife, Maria Fitzherbert.

As a sixteen-year-old boy from Fife, an ensign with the First Regiment of Foot, James had entered this world with awe. After surviving the disaster of the Walcheren Expedition, he returned a worldly warrior, able to take his place at his aunts table and enjoy what he recalled fondly as her benevolence, a readiness to share with others her purse, her tears, or her joys an absence of all selfishness. Often in the years that followed he observed her sparkle at the centre of Regency society, noted how she could change a dull party into an agreeable one... make the dullest speak, the shyest feel happy and the witty flash fire. With it all, she mixed as easily with the lowly as the high-born, with servants as well as aristocrats.

I loved her as a mother, James recalled, and so did all who dwelt under her roof.

Because of their intimacy, he was also able to see the paradoxes within. When asked after her death to describe her character, he stepped carefully over awkward terrain. It was, he said, no easy matter to draw the portrait of one whose charms and weaknesses were so intermingled, where shades and sunshine chased each other so rapidly over the landscape.

In a more candid age it might have been admitted that kind Aunt Barnard was always seen by some of their family as dangerously unconventional, a character too colourful for propriety. Her sins were usually put down to the wilfulness she had shown as the young Lady Anne Lindsay and although the details were never very clear, some light was cast on the subject in her later years when James was drawn into a family dispute. Anne had largely withdrawn from society by then and, assisted by her young protge, was writing a personal memoir. She had always been a compulsive chronicler and so absorbed was she by the task that she became a virtual recluse. The sagacious hint I am turning Methodist, she reported gleefully. Meanwhile, the reputable side of the family watched in consternation, fearful of what Anne might surprise them with next. Finally, she was urged to stop. It made no difference that she insisted her memoirs were intended purely for relatives. Her youngest sister, married to the prominent and respectable Lord Hardwicke, said that with her history there was a real danger they would be stolen and stories which should never see the light of day made public. So Anne turned to James and another of her nephews for support.

Eight years on, James found himself back with her papers, and her story the six volumes of memoir bound in calfskin, along with diaries, journals, literary works and a vast collection of letters. He was their custodian.

Next page