Published by La Trobe University Press,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

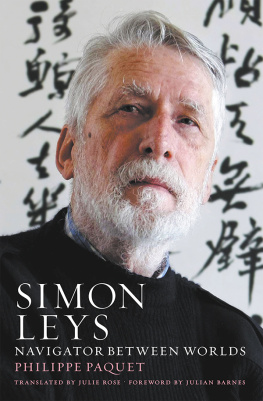

Copyright Philippe Paquet 2016

Originally published in French by Gallimard, 2016

This English translation by Julie Rose published by Black Inc. in 2017

Julie Rose asserts her right to be known as the author of this translation.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Paquet, Philippe, author.

Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds / Philippe Paquet.

9781863959209 (hardback)

9781925435566 (ebook)

Ryckmans, Pierre.

Leys, Simon, 19352014.

Authors, Belgian20th centuryBiography.

Authors, Belgian21st centuryBiography.

SinologistsBelgiumBiography.

HistoriansAustraliaBiography.

College teachersAustraliaBiography.

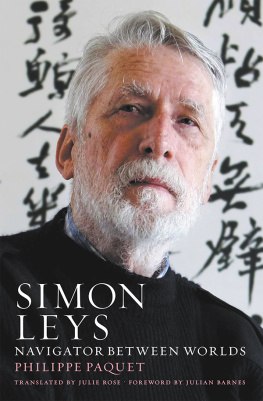

Cover design by Peter Long

Cover photograph by Ray Strange / Newspix

Text design and typesetting by Tristan Main

For my mother

Foreword

Julian Barnes

His handwriting was very particular: elegant and calligraphic; black ink, a thin nib, strokes of even weight; small lettering, but of absolute clarity. Sometimes he signed himself Simon Leys, sometimes Pierre Ryckmans; I was always Mr Barnes. We exchanged books for many years, and though we never met, had one of those distant, warm friendships which didnt require us to. It also felt to me like that rare thing, an entirely literary friendship. At one point he urged me to translate Prosper Mrimes tribute to Stendhal, H.B. I felt slightly guilty at not doing so, but my indolence proved fruitful when he decided that, if no-one else would, hed better do the job himself. I knew nothing of his private life, and we had just one friend in common, Murray Bail. Yet it also felt like a full, proper relationship: atypical, yet nonetheless full. I suspect that there were many others who had the same sort of relationship with him.

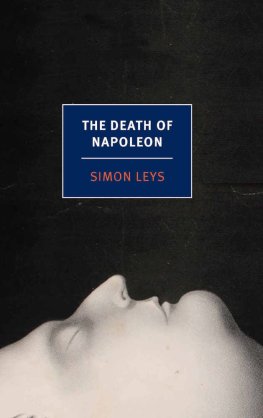

Like most, I first came to know him thanks to The Death of Napoleon, that bravura piece of droll, wrong-footing counterfactual fiction. This made his name widely known but, typically, he never wrote another novel. He evidently had no sense of a literary career: rather, a sense of where he would go and what he would write next. I recently went round my house trying to gather up the books of his I owned. With any other writer, this would be simple, since they would either be found all together, or, at worst, in two places (poetry and fiction, say). But some of Leyss were on my French shelves, alongside Stendhal; others in a catch-all section I can only label Miscellaneous Thinking. But where was his translation of The Analects of Confucius? Eventually I found it next to Epictetus. His book on the wreck of the Batavia now where was my nautical section? And what about The Death of Napoleon? It should have been among fiction, had I not lent it and never received it back (its that kind of book). His work fits no previous or current literary profile. As Mrime wrote of Stendhal, he was original in all matters a rare achievement in this age of greyness and timidity.

I was awed by his range of interests and languages; he wrote and translated in and from English, French and Chinese. When I was nineteen, I knew nothing, had barely travelled, and had no detectable ambitions. When he was nineteen, he went to China and met Zhou Enlai (admittedly with others) and wrote of that visit: My overwhelming impression was that it would be inconceivable to live in this world, in our age, without a good knowledge of the Chinese language, and a direct access to Chinese culture. In the 1970s, he was to prove a ferocious exposer of Mao and Maoism. He knew about literature, painting, poetry, calligraphy, music, politics and the sea (he spent fifteen years translating Danas Two Years Before the Mast). I trusted every word he wrote: his prose breathed integrity, though never a self-conscious integrity. He could also be sternly dismissive, suffering few fools, and clever ones not at all. Bruce Chatwin caught a lethal sideswipe; and the Parisian intelligentsia received the rough edge of his calligraphic pen. Malraux was a phony; Roland Barthess comments after a visit to China were so blithe and blind that Leyss response was simply to quote Orwell: One has to belong to the intelligentsia to believe things like that; no ordinary man could be such a fool.

In a short essay in Le Bonheur des petits poissons, Leys considers the question of writers block, a phrase which (and perhaps only he would know this) has no equivalent in either French or Chinese. But the phenomenon, of course, is universal. In this brief chronique of less than five pages, Leys refers to Conrad, Graham Greene, Jules Renard, Hemingway, Camus, Shostakovich, Flaubert, Guo Xi, Henri Michaux, D.H. Lawrence, Jean-Franois Revel, Ted Hughes, Randall Jarrell and Cyril Connolly. In another writer this might seem like showing off; with Leys, the effect is of his mind calmly and inquisitively moving from one familiar place to another, while courteously assuming that the reader will be able to follow. What in another might be arrogance, in Leys is modesty. Just as he thought it futile to chase happiness, he would have thought it intellectually vulgar to chase success. He was not a writer who sought fame. He rarely gave interviews. I dont know anyone who ever ran into him on the international literary circuit. Indeed, his absence from that noisy carousel might be taken as a rebuke to those of us who are inclined to enjoy it. But then, Leys had translated The Analects, and therefore knew that Clever talk ruins virtue (no wonder he had a run-in with Christopher Hitchens).

For thirty years he lived in Canberra, a place the outside world thinks of as somehow both important and obscure. But then, he also knew these words of The Master: A gentleman resents his incompetence; he does not resent his obscurity. For gentleman read moral being (and so, perhaps, writer). Leys was a writer of great virtue and great competence; he was obscure mainly in the minds of those who think of writing in terms of the bestseller lists. He was read by good readers in many parts of the world, and this was, I would guess, exactly what he wanted. Will this biography make him less obscure? I suspect that he would not have cared one way or the other; he would be serene about the matter. But for those of us who admire his daring, darting and capacious mind, I hope very much that it does. He may not have resented his comparative obscurity; but with his death, the rest of us are liberated to resent it on his behalf.

A good biographer basically just provides the material for a trial in which the final judgement is handed down by the reader: the mission of the first, then, is to deliver the second a file containing information that is as full and accurate as possible.

SIMON LEYS, SEGALENS EXOTICISM

Note

I have used pinyin, the official phonetic system of the Peoples Republic of China, to transcribe Chinese names. However, whenever it doesnt interfere with understanding, I have kept the transcriptions used by the authors I quote, so as to preserve the integrity of their texts along with the flavour of writings of the era (Mao Tse-tung, Chiang Ching and Lin Piao thereby cohabit with Mao Zedong, Jiang Qing and Lin Biao). The same goes for names associated with Hong Kong, Taiwan, the Chinese diaspora and non-communist China (Kowloon, Taipei, Kuomintang, Chiang Kai-shek, Lee Kuan Yew, etc.). I use Peking, and not Beijing, not out of ill-conceived nostalgia for the colonial era, but because, as Simon Leys once took the pain to explain, using Beijing in a language other than Chinese is as odd as using Lisboa or Mnchen in English. Finally, I write Tiananmen because the English reader is accustomed to this spelling, despite the fact that pinyin requires to write Tiananmen for phonetical reasons.

Next page