Music should humbly seek to please; within these limits great beauty may perhaps be found.

PROLOGUE

GOOD GOD,

WHATVE WE GOT ERE?

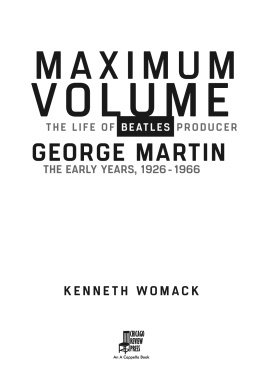

I T WAS WEDNESDAY, June 6, 1962, and George Martin was flummoxed.

For the most part, it had been a fairly quiet day in the life of the Parlophone A&R man, who, at age thirty-six, had become inured to working artists and repertoire. On most days, he navigated a breakneck schedule of back-to-back meetings and recording sessionsone after another and often from dawn until well after dusk.

But today was relaxed by comparison, quiet even. George had taken a morning meeting with David Platz, a music publisher with whom he shared several ongoing business interests. They were natural collaborators, being two thirtysomethings having made their names on the London music scene as young execs on the rise. After lunch, Georges afternoon had been devoted to his hilarious mates from Beyond the Fringe. Together, George and the comedy troupe had struck gold after the A&R man recorded their stage act on one of EMIs mobile units back in 1961. Under Georges supervision, Parlophone enjoyed a hit record with the zany quartet of Alan Bennett, Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller, and Dudley Moore. And the future looked even more promising for Georges clients, who were set to open Beyond the Fringe on Broadway in just a few short months.

For George, good old British comedy had proven to be his salvation, saving his beleaguered record label in the bargain. But what he really wanted, truth be told, was to handle a beat group. He was absolutely driven by the notion of landing a rock combo, ferreting out hit songs for them, and generating one chart-topper after another. In his heart of hearts, what he longed for most was something along the lines of Cliff Richard and the Shadows, the beat music wunderkinds who recorded for Norrie Paramor, Georges opposite number with EMIs Columbia imprint. George was incredibly jealous of Norrie, especially since the Columbia A&R man had scored one chart sensation after another with Cliff Richard, who had emerged as Norries apparently unstoppable hit-making vehicle. Thats what George wanted all rightto develop a beat music juggernaut to rival Paramors and enjoy the good life for a change. Who wouldnt? It was well known around the EMI corridors that Norrie tooled around the city in his brand-new E-Type Jaguarwhen he wasnt driving his sports car out to his seaside place on the Sussex coast, that is. Oh, George definitely wanted a Jag. Of that he was certain.

After a dinner break, George made his way to Abbey Road with Ron Richards, his assistant A&R man, strolling beside him. It was an early summer day in London as the two Parlophone colleagues contemplated the evenings recording session. How had they found themselves in such a position in the first place, having signed a contract with the very same Liverpool beat group that George had rebuffed back in February? George didnt hear anything earth-shattering in their sound, as he had told their manager, Brian Epstein, on that very first day when he played their acetate in his office. Walking toward the studio on that June evening, George and Ron still couldnt wrap their minds around the bands strange-sounding moniker. Bloody silly name that is, Beatles, Richards said. How corny can you get? For the life of him, George couldnt figure out how they would even go about marketing them. Was it going to be John Lennon and the Beatles, or Paul McCartney and the Beatles? George wondered.

When they arrived at Abbey Road, Richards made his way to the studio, while George occupied himself in the canteen. Let Ron, his more-than-capable assistant, handle the sessionRon fancied himself as Parlophones resident rock n roll man, after all. Its not like George was missing out on some groundbreaking moment in the presence of the next Elvis, as Brian Epstein had boasted back in February. Besides, EMI was incurring all of the session and production costs, which would never hit Georges Parlophone budget. And what was the Beatles contract worth anyway? It was a penny-per-record dealno great investment on EMIs part. As Brian eagerly scanned the agreement in May, George knew something that the novice manager probably hadnt fully grasped: the Beatles contract called for recording a mere six sidesnothing more, nothing less. How long, really, would it take to knock off a half dozen measly songs anywaya few wasted hours at most?

And thats when tape operator Chris Neal found George in the canteen, telling him that he was wanted in the studio. Apparently the Beatles had already caused quite a stir around Abbey Road. Good God, whatve we got ere? balance engineer Norman Smith had muttered to himself when the bandmates ambled into Studio 2. Their equipment was so ratty and tattered that Abbey Roads white-coated personnel had to rig up a series of work-arounds just to get the session started. As Richards and Smith stared in wonder verging on outright disgust, the Beatles had ripped off a cover version of Bsame Mucho before playing a composition of their own called, of all things, Love Me Do. When did beat bands begin writing their own tunesespecially beat bands from Liverpool?

Moments later, George made the scene, joining his EMI colleagues in the control room above the studio floor. There they were, standing before him for the very first time: twenty-one-year-old John Lennon on rhythm guitar, nineteen-year-old Paul McCartney on bass, nineteen-year-old George Harrison on lead guitar, and twenty-year-old Pete Best on drums. As George looked on, the band played two more original compositions called P.S. I Love You and Ask Me Why. With four songs under their belts, the band members joined George and his team up in the control room. Without saying a word, the lanky ex-navy man commanded their full attention. Towering over them in his neat, well-pressed suit, George looked, for all intents and purposes, like pure, upper-crust London to these rural, North Country Scousers from Liverpool. And when he opened his mouth, George spoke with a posh accent to boot. He couldnt have been any more intimidating if he tried.

As the boys fired up their cigarettes, George took the floor. And for the next twenty minutes, he lectured his much younger charges, mercilessly critiquing nearly every aspect of their performance, from the slipshod nature of their vocal delivery to their sloppy musicianship. He even took issue with the way John Lennon played his harmonica during Love Me Do. Eventually, the veteran A&R man brought his lengthy, scathingly candid diatribe to an end, and he actually began to feel sorry for the Beatles, having railed against them for so long.

![Lambley - And the Band Begins to Play: [Part6 The Definitive Guide to the Beatles Rubber Soul]](/uploads/posts/book/213742/thumbs/lambley-and-the-band-begins-to-play-part6-the.jpg)