All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, without written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review.

All images from the authors collection, except as follows: Beatles songbook courtesy of Garry Day; Got to Get You into My Life sheet music courtesy of Pete Nash from the British Beatles Fan Club; Teen Life cover courtesy of Guy Barbier. Thanks also to Robert Brundish and to Noah Fleischer / Heritage Auctions.

Every reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders and secure permissions. Omissions can be remedied in future editions.

Revolver: how the Beatles reimagined rock n roll / Robert Rodriguez.

p. cm.

Includes .

1. Beatles. Revolver. 2. Beatles. 3. Rock music--1961-1970--History and criticism. I. Title.

Did you ever dream about a place you never really recall being to before? A place that maybe only exists in your imagination? Some place far away, half-remembered when you wake up. When you were there, though, you knew the language, you knew your way around. That was the 60s. [Pause.] No, it wasnt that either. It was just 66 and early 67. Thats all it was.

Terry Valentine (Peter Fonda) in The Limey, 1999

F or too many years, assessments of the Beatles recorded output have routinely placed their 1967 release, Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band, atop the heap. The acclaim it received upon its arrival has echoed onward through the years as critics and a large segment of the fan population view it as the groups finest effort, an album that influenced everything that followed and set the standard against which all other acts would be measured.

Until perhaps the last decade or so, this was a common consensus. Other albums produced by the group might be better loved (Abbey Road comes to mind) or may have stirred more powerful feelings of personal nostalgia (Capitols Meet the Beatles! was life-changing for the generation coming of age when it was new), while certain Beatles LPs ended up more respected than revered (e.g., 1968s sprawling White Album was seen by some as unfocused and self-indulgent in places: number nine, number nine ). Yet it was Sgt. Pepper that seemed to live at the apex of the Beatles creativity. Everything about it projected Importance, from its grandiose cover artwork to its apocalyptic ending chordno rock album had ever seemed so much bigger than the sum of its tracks.

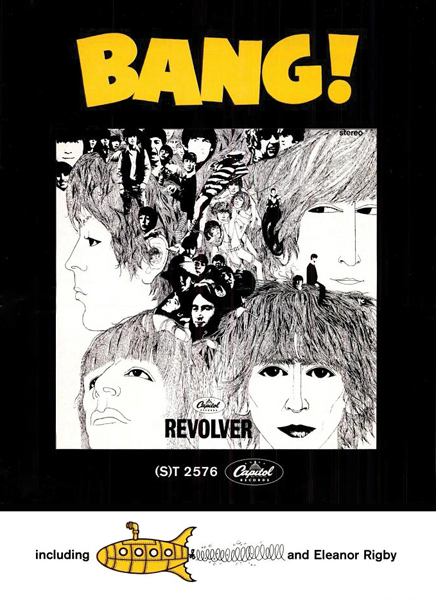

Currently, a dark horse within the Beatles oeuvre has challengedand in many instances, bestedthat album for supremacy in lists assessing the groups finest work. Unlike Sgt. Pepper, the 1966 release of Revolver wasnt a major media event. There was no speculative buildup or public wondering about what the Beatles were about to unleash. Further, its issue came under a cloud: just as the band were preparing to undertake what became their final tour, a scandal prompting bannings and bonfires swept America, dwarfing their stunning achievement.

Knowledgeable fans noted too that what emerged in the U.S. was not even representative of the groups artistic intent, being an eleven-track condensation of what the rest of the world was getting to hear. (Three John Lennon compositionsIm Only Sleeping, And Your Bird Can Sing, and Doctor Robertwere withheld from U.S. editions of Revolver while the sessions were in progress, and used as padding on an earlier stateside release to feed the insatiable demand for new product by Capitol, their American label.) Not only was the album overshadowed by collateral concerns, butas presented in the worlds biggest marketit didnt even represent fulfillment of the groups vision.

Revolver is the Beatles artistic high-water mark. For a start, unlike Pepper, it was a true group collaboration. Their work would increasingly take on the appearance of a musical co-op, with three members supporting the fourth members individual pursuits; but with Revolver, the music bears all the evidence of the group as a whole being fully vested in creating Beatle music.

For the first time, studio technology was deliberately incorporated into the conception of the recordings they made, rather than used merely as a tool to capture performances. Suddenly, the possibilities of what a rock band could aspire to create were not limited by what they were expected to reproduce onstage. Pushing the studios technological limits, they now sought to capture sounds previously unheard and in their heads, conscious of their place in rocks hierarchy and driven by the need to stay ahead of the competition. With this, the concept of the recording artist was born.

Only an act on their level of success could demandand getalmost unlimited studio time to pursue their artistic agenda. Enabling them were longtime producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, visionaries equal to the task of looking past what had been done and seeing what could be, fulfilling the Beatles collective ambitions and inspiring them to reach for even greater heights. Their talents were as key to Revolvers success as were the Beatles own, resulting in a working relationship unique within their peer group.

Nineteen sixty-six was a year that saw major change in rock music as the dichotomy between pursuing chart success and aspiring to create something new forced many acts to choose sides. While the Beatles were able to stride both paths, seemingly with ease, others werent so lucky. Perhaps the Beatles closest artistic rival during this period, Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, attempted to do both; but when Pet Sounds, his crowning achievement, failed to engage the masses, he was pressured by his bandmates and his label to abandon the pursuit of perfection and higher ideals, resulting in one of rocks most notorious breakdowns.

Sgt. Pepper, in contrast to its predecessor, is inextricably tied to its time: a pleasant period piece but a period piece nonetheless; not so Revolver, an album crackling with potent immediacy. Its been said that it sparked subgenres with every track, anticipating electronica (Tomorrow Never Knows); punk (the abrasive sneer of Taxman); Baroque rock (For No One); and world music (Love You To), among other subgroupsand all within the space of fourteen tracks. Its very eclecticism may have worked against it in the short run, making it difficult to pigeonhole, but today is seen by many as its most appealing quality.

The depth of the songcraft evident on Revolver is hard to better. While John and George broadened their horizons, addressing such subjects as politics, pill pushers, and the illusory nature of the material world, Paul reached the top of his game, offering up sharply etched portraits of romantic breakdowns and societal isolation, balanced with sunny optimism. One thing the Beatles didnt do on this album was shy away from dark themes. In contrast, much of