Antithetical Arts

Antithetical Arts constitutes a defence of musical formalism against those who would put literary interpretations on the absolute music canon. In Part I, the historical origins of both the literary interpretation of absolute music and musical formalism are laid out. In Part II, specific attempts to put literary interpretations on various works of the absolute music canon are examined and criticized. Finally, in Part III, the question is raised as to what the human significance of absolute music is, if it does not lie in its representational or narrative content. The answer is that, as yet, philosophy has no answer, and that the question should be considered an important one for philosophers of art to consider, and to try to answer without appeal to representational or narrative content.

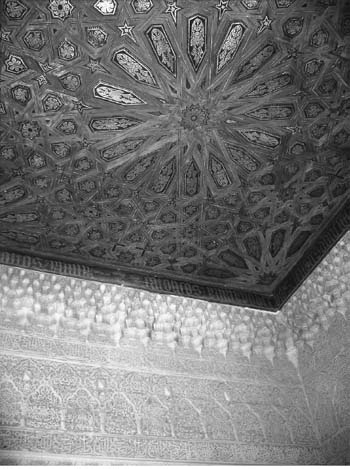

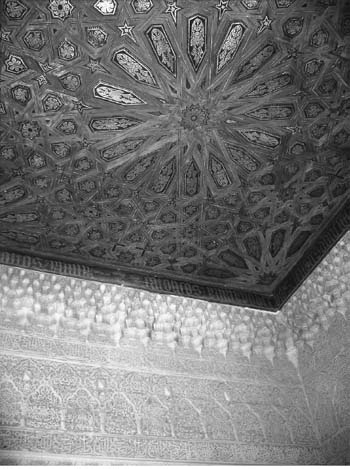

Frontispiece: The Alhambra Palace, Granada, Spain

Photograph by Joan Pearlman

Antithetical Arts

On the Ancient Quarrel between Literature and Music

Peter Kivy

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Peter Kivy 2009

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2009

First published in paperback 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Kivy Peter.

Antithetical arts: on the ancient quarrel between literature and music / Peter Kivy.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780199562800

1. Music and literature. 2. Absolute music. I. Title.

ML3849.K57 2009

780.08dc22

2008048452

Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry India.

Printed in the United Kingdom by

Lightning Source UK Ltd., Milton Keynes.

ISBN 978019562800 (Hbk)

ISBN 9780199596294 (Pbk)

To Anthony Pryer

and the music students

at Goldsmiths College,

University of London,

but for whom I would

have been a stranger

in a strange land.

Preface

The ancient quarrel with which I deal in this book is neither ancient in the sense of dating back to antiquity, nor ancient in the sense of being very very old. It is old, to be sure, by ordinary standards, having its beginnings in the rise of pure instrumental music in the second half of the eighteenth century. Thus it is close on two hundred and fifty years old, which is old enough: a good deal older, one supposes, than the Ancient Mariner, who, Coleridge thought, deserved the epithet.

Philosophers will, of course, recognize the allusion, in my title, to Platos description, in Republic X, of an ancient quarrel between philosophy and poetry; of which there are many proofs.... So there is, really, no reason to make heavy weather of the distinction between ancient and old. But ancient quarrel is the phrase that has endured and is how Platos assertion is customarily quoted. So ancient quarrel is how my quarrel will be characterized, although long-standing is closer to the literal truth.

My ancient quarrel is not between philosophy and any one of the arts, although that quarrel has certain affinities with mine, as we shall see. It is, rather, an internal quarrel, as it were: an internecine conflict within the arts, between the emerging art of absolute music, as the Romantics called it, music alone, as I sometimes refer to it, and the truly ancient, long-established art of literary fiction. And it arises, as we shall see, in the attempt to understand, interpret, appreciate the newly emerging absolute music canon, on the part of those who were present at the creation. It is, in other words, a quarrel between those who insist on understanding, interpreting, appreciating music alone in, broadly speaking, literary terms, and those, customarily called formalists, who insist on understanding, interpreting, appreciating absolute music in, broadly speaking, its own terms, whatever those terms may ultimately turn out to be.

I am no neutral observer of this ancient quarrel. I am on the side of the formalists. But this book will be more a critique of the opposition than a defense of absolute musics autonomy. For it seems to me that although the progress to formalism in the early years was a struggle against the literary crowd, after it was a going concern it became and, I believe still is, the one to beat, not the one in need of defense. The burden of proof, I strongly believe, is on those who wish to placeit is very tempting for me to say imposeliterary and other semantic interpretations on the absolute music canon.

In Part I, I have tried to lay bear what, from a philosophers point of view, at least this philosophers point of view, seem to be the conceptual origins of musical formalism, and the origin of its quarrel with the literary arts. It is decidedly not meant to be a history of musical formalism, which so far as I know, has never been written, nor am I qualified to write it, or interested in writing it, even if I could.

Part II is composed of chapters that engage the literary interpreters of the absolute music canon. It is critical throughout.

Finally, in Part III, although I continue to engage the literary interpreters in debate, I also try to say something positive about the future of musical formalismhow it must proceed if it is to address the very real philosophical problems that it faces. For formalism, it is not all beer and skittles, as I know full well. And this book ends, alas, not with the solution, but with the problem.

Although some of the chapters started life as separate essays, this is not an essay collection but a book with an argument, begun in the first chapter and concluded in the last. Nevertheless, there are bound to be some readers who will not be keen on working their way through the intricacies of scholarship and interpretation in Part I, where the historical foundations of formalism are laid out. For those readers, no great harm will be done by skipping the historical material altogether and going straight on to Part II, where the contemporary argument begins. Naturally, though, I hope those so inclined will overcome their aversion, and begin at the beginningthat is because I think knowing the historical origins of the debate makes the current debate itself far more understandable. Had I not thought so, I would have cut to the chase. But here, as elsewhere, what precedes the chase makes sense of the chase.

Next page