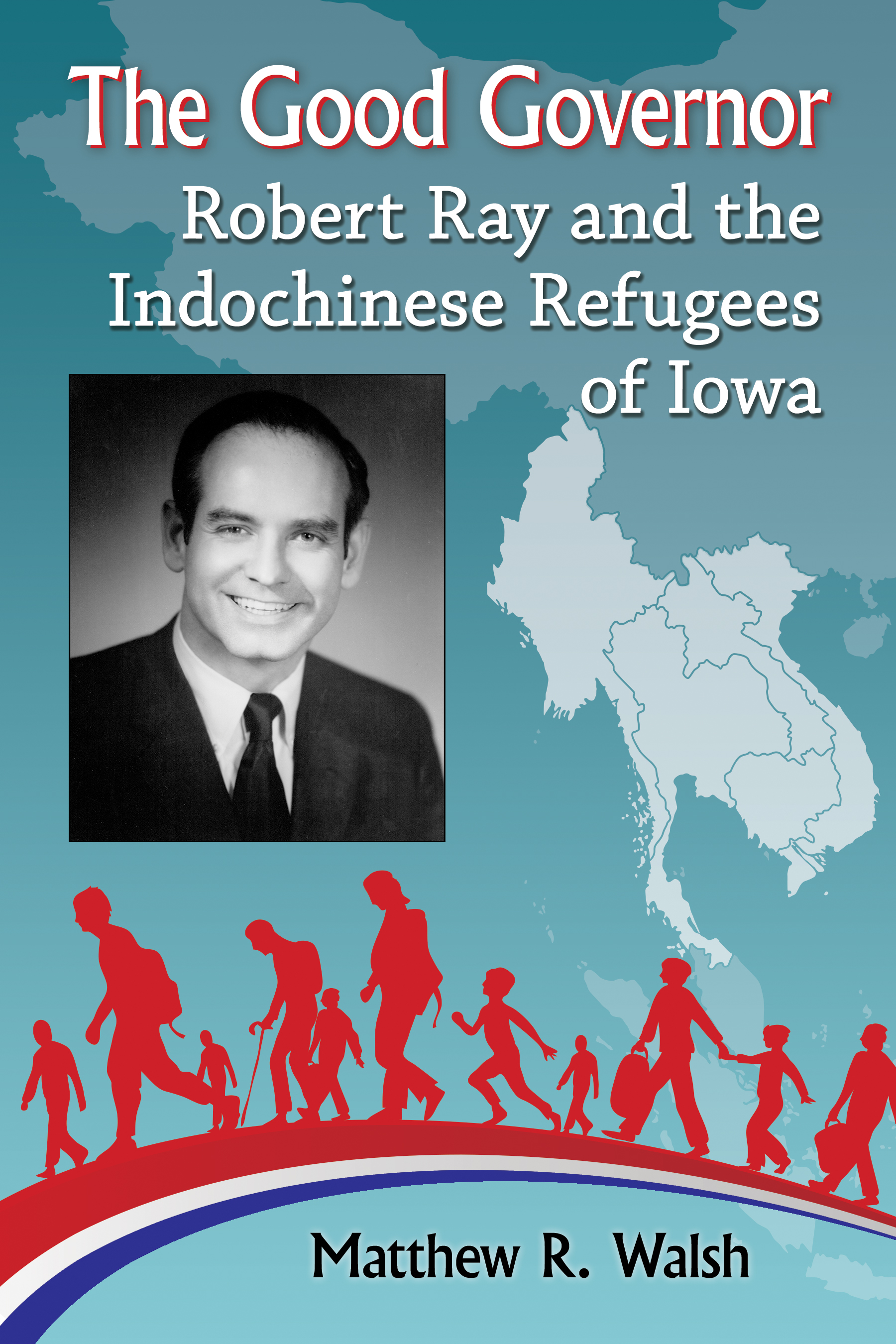

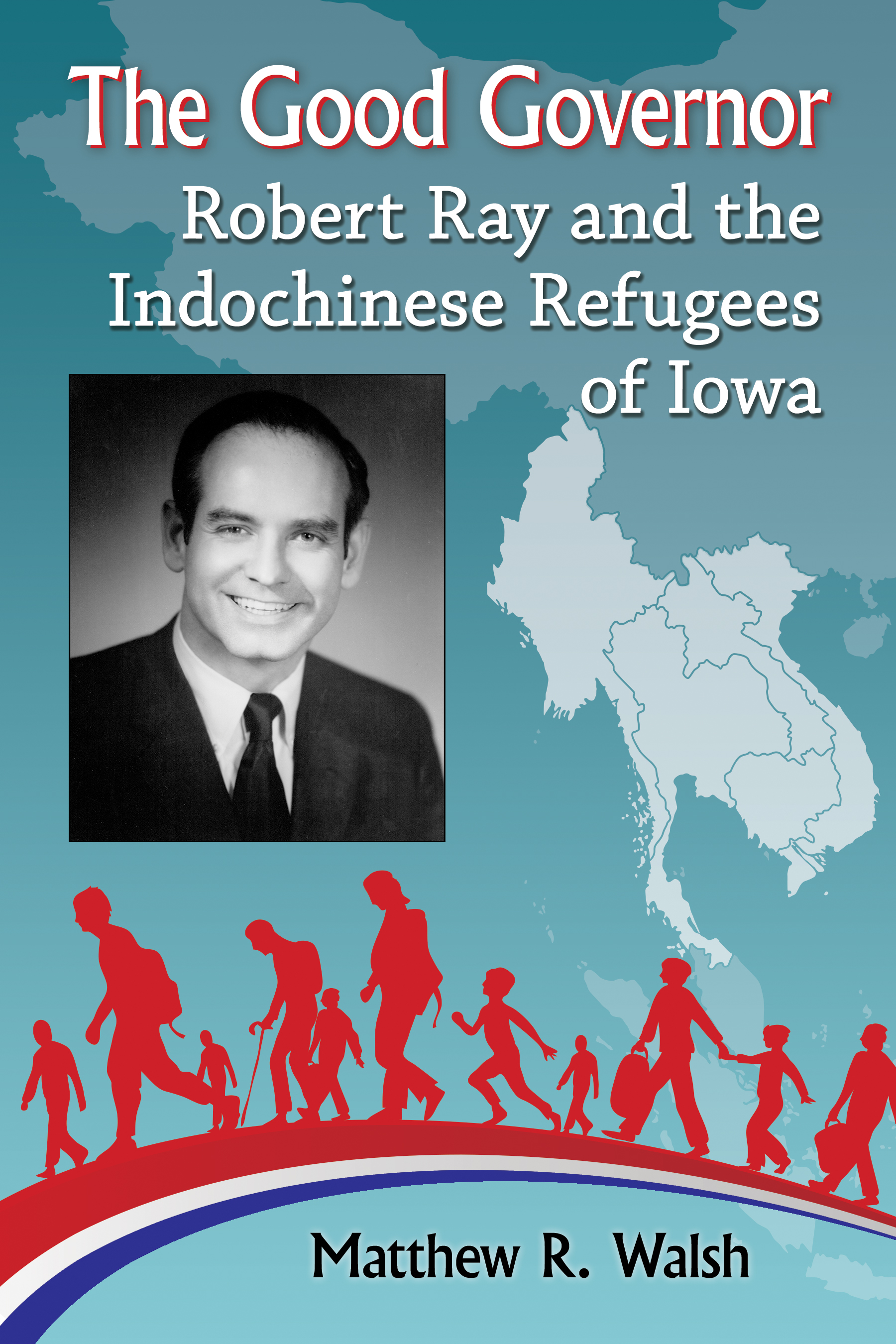

THE GOOD GOVERNOR

Robert Rayand the Indochinese Refugees of Iowa

Matthew R. Walsh

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2888-2

2017 Matthew R. Walsh. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: Governor Robert Ray, circa 1969, Des Moines, Iowa (State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines); background images 2017 iStock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For my son Nolan

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I must thank those who shared their experiences with me, especially Iowas Indochinese refugee community. In particular, Houng Baccam, Som Baccam, Siang Bachti, Matsalyn Brown, Wing Cam, and Dinh VanLos contributions to this project must be recognized.

I am also indebted to David Gavin and Pamela Riney-Kehrberg for reviewing the manuscript and offering suggestions for improvement.

Most of my archival work was conducted at the State Historical Society of Iowa in Des Moines, and the entire staff there provided an ideal research environment.

Finally, I would like to thank the Ray family and the families of all public servants. Though it is an individual who is elected or appointed to a position, his or her entire family serves too.

Preface

In December of 2008, I accepted a teaching position at Des Moines Area Community Colleges Urban Campus. To my longtime girlfriends horror, I would be moving from the Pittsburgh area to Iowa. In dismay, my girlfriend (and future wife Dana) quipped, Have fun sitting on wicker furniture and flirting with farm girls in Iowa. Worse yet, some of my acquaintances began asking if I liked potatoes. Had they just realized my Irish surname? No, they had just confused Iowa with the state of Idaho. I, too, had false expectations about the Hawkeye state; I anticipated teaching students of mostly German and northern European ancestry. To my surprise, names like Baccam, Chau, Dzaferagic, Nguyen, and Yousif dotted my class roster. I soon learned that much of the states diversity stemmed from its long history of resettling refugees. It is hoped that this book combats the stereotype of Iowa as a land of all white farmers.

My coworker Laura Douglas first suggested Indochinese refugee resettlement as a research topic. After watching the compelling Iowa Public Television documentary A Promise Called Iowa, I wanted to learn more about resettlement during Governor Rays term in office. Soon thereafter, I obtained permission to use the Robert D. Ray Papers at the State Historical Society of Iowa. Rays refugee program papers are unique in that only the state of Iowa operated as a resettlement agency throughout the postVietnam War years; private organizations carried out this work in all other states. These papers allowed a detailed look into the states refugee program from 1975 through 1982.

The richest sources in the archives were the hundreds of letters sent to the Governors Office. Iowans wrote with such candor and in detail about why they approved or disapproved of Rays refugee policy; this has resulted in a more nuanced look at American attitudes on Indochinese refugee resettlement than the basic numbers from opinion polls used by other scholars. People corresponded from outside of Iowa too. One annoyed Texan cynically asked Ray to take all of the wetback Mexicans from his state. Other Americans compared their governors inaction to Rays humanitarianism. From Asia, refugees like Dr. Tam Khac Nguyen wrote because they had heard Iowa had a good governor who might be willing to help. After reading all the documents, I have concluded that Ray is one of the most overlooked humanitarians of the twentieth century. Though his name appears in the title and his position on refugee matters is detailed, this book is not a biography of Robert Ray. Hopefully, this book about Rays refugee program will spark someones interest, and a full biography he is so deserving of will be written in the near future.

In addition to the Ray Papers, oral history interviews with public officials and refugees informed my arguments. I would describe myself as having a polite yet reserved personality. Looking back, I am surprised by the lengths to which I went to contact potential interviewees, but I was so fascinated that I needed to learn more. At a citizenship ceremony, I approached Ray, a former governor, and told him about my project. Later, I walked into the World Food Prize headquarters and asked to interview Kenneth Quinn, a former U.S. ambassador. I cold-called numbers from phonebooks and internet searches. I asked a church employee about one of its parishioners. One individual was tracked down through the county assessors property listing webpage, and then I wrote him a letter explaining my project. Connections were made with Tai Dam by attending their New Year celebration and emailing officers listed on the Tai Villages webpage. After these initial contacts, snowball sampling led to even more interviews. All participants signed an informed consent document detailing the voluntary nature of the project, and my desire to share their insights via publication.

Interviews were conducted at local libraries, private homes, the Tai Village, Des Moines Area Community College, and the workplaces of some of the participants. A list of questions guided interviews, but they were generic and intended to get the interviewee to open up. Sessions ranged from about forty-five minutes to over two hours in length. Light editing occurred during transcription. Literal translation was avoided because I did not want to perpetuate stereotypes about Asian Americans speaking broken English. Pauses such as um, ah, and repetitions were removed. This was also done for native English speakers to help the narrative flow. Family members served as translators in less than a handful of interviews.

For some of the refugees, speaking about their traumatic past was cathartic. I can admit that for others, old wounds had been reopened. Initially, I began to ask myself why on Earth any of these people would speak to me, a complete stranger, about these intimate wartime experiences. Then, I realized that the Iowa Tai Dam has never been covered, and participants wanted that to change. Since so few people know anything about this ethnic minority from northwest Vietnam, a major goal of this book was to provide the Tai Dams perspective. Any resettlement history that focuses on Robert Ray and the states viewpoint is not complete. The Tai Dams cultural background and experiences in war torn Southeast Asia directly influenced their successful resettlement, and their voice must be heard.

In the pages that follow, readers will be walked through some of the darkest chapters in human history. Rape in Southeast Asia, starvation in Pol Pots killing fields, torture in communist prison camps, death in the Indochina Wars, and racism in America are detailed. Nevertheless, the chronicle of refugee resettlement in Iowa is ultimately a positive one. That is because of the humanitarianism of a governor, the compassion of many Iowans, and most importantly, the resiliency of the refugees.

Next page