To Chris, Kristen, Lauren, and Erin, for making it all worthwhile

and to Molly, whose lust for socks kept us all on our toes

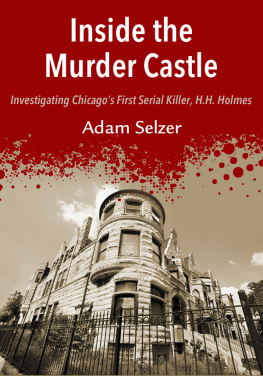

Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir mens blood. D ANIEL H . B URNHAM

D IRECTOR OF W ORKS

W ORLD S C OLUMBIAN E XPOSITION, 1893 I was born with the devil in me. I could not help the fact that I was a murderer, no more than the poet can help the inspiration to sing. D R. H. H. H OLMES

C ONFESSION

1896

I LLUSTRATION C REDITS

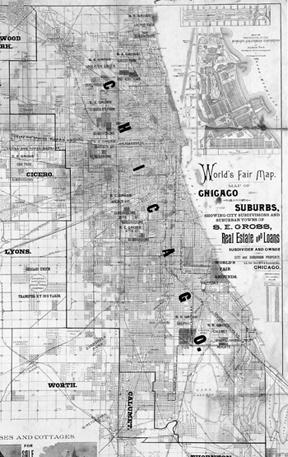

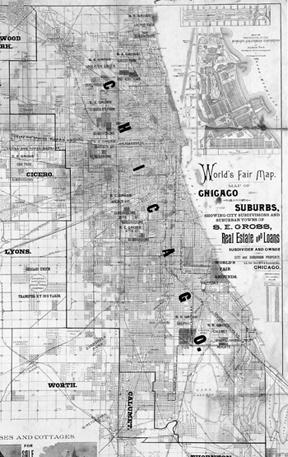

Map: Rascher Publishing Company. Chicago Historical Society (ICHi31608).

Prologue: Worlds Columbian Exposition Photographs by C. D. Arnold, Ryerson and Burnham Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago. Photograph courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Part I: Chicago Historical Society. ICHi21795.

Part II: Worlds Columbian Exposition Photographs by C. D. Arnold, Ryerson and Burnham Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago. Photograph courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Part III: Photograph by William Henry Jackson. Chicago Historical Society. ICHi17132.

Part IV: Bettman/CORBIS

Epilogue: Chicago Historical Society. ICHi25106.

Notes and Sources: Chicago Historical Society. ICHi17124.

Chicago, 1891.

E VILS I MMINENT

(A N OTE )

I N C HICAGO AT THE END of the nineteenth century amid the smoke of industry and the clatter of trains there lived two men, both handsome, both blue-eyed, and both unusually adept at their chosen skills. Each embodied an element of the great dynamic that characterized the rush of America toward the twentieth century. One was an architect, the builder of many of Americas most important structures, among them the Flatiron Building in New York and Union Station in Washington, D.C.; the other was a murderer, one of the most prolific in history and harbinger of an American archetype, the urban serial killer. Although the two never met, at least not formally, their fates were linked by a single, magical event, one largely fallen from modern recollection but that in its time was considered to possess a transformative power nearly equal to that of the Civil War.

In the following pages I tell the story of these men and this event, but I must insert here a notice: However strange or macabre some of the following incidents may seem, this is not a work of fiction. Anything between quotation marks comes from a letter, memoir, or other written document. The action takes place mostly in Chicago, but I beg readers to forgive me for the occasional lurch across state lines, as when the staunch, grief-struck Detective Geyer enters that last awful cellar. I beg forbearance, too, for the occasional side journey demanded by the story, including excursions into the medical acquisition of corpses and the correct use of Black Prince geraniums in an Olmstedian landscape.

Beneath the gore and smoke and loam, this book is about the evanescence of life, and why some men choose to fill their brief allotment of time engaging the impossible, others in the manufacture of sorrow. In the end it is a story of the ineluctable conflict between good and evil, daylight and darkness, the White City and the Black.

E RIK L ARSON

S EATTLE

P ROLOGUE

Aboard the Olympic

1912

The architects (left to right) : Daniel Burnham, George Post, M. B. Pickett, Henry Van Brunt, Francis Millet, Maitland Armstrong, Col. Edmund Rice, Augustus St. Gaudens, Henry Sargent Codman, George W. Maynard, Charles McKim, Ernest Graham, Dion Geraldine.

Aboard the Olympic

T HE DATE WAS A PRIL 14, 1912, a sinister day in maritime history, but of course the man in suite 6365, shelter deck C, did not yet know it. What he did know was that his foot hurt badly, more than he had expected. He was sixty-five years old and had become a large man. His hair had turned gray, his mustache nearly white, but his eyes were as blue as ever, bluer at this instant by proximity to the sea. His foot had forced him to delay the voyage, and now it kept him anchored in his suite while the other first-class passengers, his wife among them, did what he would have loved to do, which was to explore the ships more exotic precincts. The man loved the opulence of the ship, just as he loved Pullman Palace cars and giant fireplaces, but his foot problem tempered his enjoyment. He recognized that the systemic malaise that caused it was a consequence in part of his own refusal over the years to limit his courtship of the finest wines, foods, and cigars. The pain reminded him daily that his time on the planet was nearing its end. Just before the voyage he told a friend, This prolonging of a mans life doesnt interest me when hes done his work and has done it pretty well.

The man was Daniel Hudson Burnham, and by now his name was familiar throughout the world. He was an architect and had done his work pretty well in Chicago, New York, Washington, San Francisco, Manila, and many other cities. He and his wife, Margaret, were sailing to Europe in the company of their daughter and her husband for a grand tour that was to continue through the summer. Burnham had chosen this ship, the R.M.S. Olympic of the White Star Line, because it was new and glamorous and big. At the time he booked passage the Olympic was the largest vessel in regular service, but just three days before his departure a sister shipa slightly longer twinhad stolen that rank when it set off on its maiden voyage. The twin, Burnham knew, was at that moment carrying one of his closest friends, the painter Francis Millet, over the same ocean but in the opposite direction.

As the last sunlight of the day entered Burnhams suite, he and Margaret set off for the first-class dining room on the deck below. They took the elevator to spare his foot the torment of the grand stairway, but he did so with reluctance, for he admired the artistry in the iron scrollwork of its balustrades and the immense dome of iron and glass that flushed the ships core with natural light. His sore foot had placed increasing limitations on his mobility. Only a week earlier he had found himself in the humiliating position of having to ride in a wheelchair through Union Station in Washington, D.C., the station he had designed.

The Burnhams dined by themselves in the Olympic s first-class salon, then retired to their suite and there, for no particular reason, Burnhams thoughts returned to Frank Millet. On impulse, he resolved to send Millet a midsea greeting via the Olympic s powerful Marconi wireless.

Burnham signaled for a steward. A middle-aged man in knife-edge whites took his message up three decks to the Marconi room adjacent to the officers promenade. He returned a few moments later, the message still in his hand, and told Burnham the operator had refused to accept it.

Footsore and irritable, Burnham demanded that the steward return to the wireless room for an explanation.

Millet was never far from Burnhams mind, nor was the event that had brought the two of them together: the great Chicago worlds fair of 1893. Millet had been one of Burnhams closest allies in the long, bittersweet struggle to build the fair. Its official name was the Worlds Columbian Exposition, its official purpose to commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of Columbuss discovery of America, but under Burnham, its chief builder, it had become something enchanting, known throughout the world as the White City.

It had lasted just six months, yet during that time its gatekeepers recorded 27.5 million visits, this when the countrys total population was 65 million. On its best day the fair drew more than 700,000 visitors. That the fair had occurred at all, however, was something of a miracle. To build it Burnham had confronted a legion of obstacles, any one of which could have should havekilled it long before Opening Day. Together he and his architects had conjured a dream city whose grandeur and beauty exceeded anything each singly could have imagined. Visitors wore their best clothes and most somber expressions, as if entering a great cathedral. Some wept at its beauty. They tasted a new snack called Cracker Jack and a new breakfast food called Shredded Wheat. Whole villages had been imported from Egypt, Algeria, Dahomey, and other far-flung locales, along with their inhabitants. The Street in Cairo exhibit alone employed nearly two hundred Egyptians and contained twenty-five distinct buildings, including a fifteen-hundred-seat theater that introduced America to a new and scandalous form of entertainment. Everything about the fair was exotic and, above all, immense. The fair occupied over one square mile and filled more than two hundred buildings. A single exhibit hall had enough interior volume to have housed the U.S. Capitol, the Great Pyramid, Winchester Cathedral, Madison Square Garden, and St. Pauls Cathedral, all at the same time. One structure, rejected at first as a monstrosity, became the fairs emblem, a machine so huge and terrifying that it instantly eclipsed the tower of Alexandre Eiffel that had so wounded Americas pride. Never before had so many of historys brightest lights, including Buffalo Bill, Theodore Dreiser, Susan B. Anthony, Jane Addams, Clarence Darrow, George Westinghouse, Thomas Edison, Henry Adams, Archduke Francis Ferdinand, Nikola Tesla, Ignace Paderewski, Philip Armour, and Marshall Field, gathered in one place at one time. Richard Harding Davis called the exposition the greatest event in the history of the country since the Civil War.