SEYMOUR HERSH

Seymour Hersh Scoop Artist

Robert Miraldi

2013 by Robert Miraldi

All rights reserved. Potomac

Books is an imprint of the

University of Nebraska Press.

Manufactured in the United

States of America

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Miraldi, Robert.

Seymour Hersh: scoop artist /

Robert Miraldi.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical

references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Hersh, Seymour M. 2. Journalists

United StatesBiography. 3.

United StatesPolitics and government

19451989. 4. United StatesPolitics and

government19895. United States

Foreign relations19451989. 6. United

StatesForeign relations1989 I. Title.

PN4874.H473M57 2013

070.92dc23 [B] 2013023619

Set in Lyon by Laura Wellington.

Designed by Nathan Putens.

To Mary Beth Pfeiffer, who understands investigative reportingand me.

Contents

Illustrations

Following page

Prologue

Chasing Sy Hersh

I have been chasing Sy Hersh, Americas quintessential investigative reporter, for twenty-five years. He did not know it, however, until five years ago.

I first met Seymour Myron Hersh in the fall of 1985 when he was forty-eight years old. I had invited him to speak at my university, a small state college seventy-five miles from New York City near the Hudson River, where I taught journalism for thirty years. His controversial best-selling book, The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House, had come out in the spring, and his speaking fee had doubled, from $2,000 to $4,000, although we got him at the bargain rate. (He now commands $20,000 a speech.) My office was located in a remote part of the 257-acre campus, and I hoped Hersh could find me. He was scheduled for an afternoon workshop with journalism students. He arrived fifteen minutes before showtime. This is a tough place to find, he said. Well, I answered, I figured if you could find Calley at Fort Benning, you could find my office. He shuffled his feet in an aw-shucks manner, looked away, and said, That was a long time ago. It had been sixteen years ago, actually, since he had tracked down the notorious William Calley who ordered the killing of nearly five hundred Vietnamese civilians in the village of My Lai in 1968. Hershs expos earned him the Pulitzer Prize in journalism and cemented his fame.

As we walked across campus I told him how my wife, an investigative reporter, worried so much each time she published. We all worry, he said. We are out there alone. His book on Kissinger was bringing howls of protest from the former secretary of states minions, and one minor participant in the plotline had sued Hersh for $50 million, although it ultimately was resolved in Hershs favor.

At the workshop that afternoon I could not get him to discuss journalistic technique for the students I had asked to attend. Instead, he wanted to talk about the CIA, intelligence gathering, Richard Nixon, and Kissinger. The reporter did not want to talk about reportingonly what he had uncovered in the process of reporting. Like all the great journalists, his passion was reserved for the issues. Form and function were of little interest.

Before his evening lecture, the college president hosted a dinner at her home. The president invited vice presidents, deans, and local officials. This kid from Chicago, the son of immigrant parents, a law school dropout and former Chicago crime reporter, was a celebrity, a fucking celebrity, as he called himself in a triumphant post-Pulitzer interview. One guest was Alan Chartock, a political science professor who was also a well-known personality on a network of National Public Radio stations he ran from the state capital in Albany. Hersh had a Washington DC neighbor whom Chartock knew. Hersh liked the man; Chartock did not. They proceeded to argue about him over dinner. When he left the dinner, Hersh said to me, Who is that little prick? I explained he is a considerably influential pundit in New Yorks capital. Hersh just uttered more profanities. Hersh seldom minces words or pulls punches, I came to learn. He goads and blusters and intimidates, leaving enemies everywhere he goes, from presidents to generals to secretaries of state. It is part of his styleand success.

The evening lecture went better. Nearly 750 people packed the colleges largest lecture hall. Hersh had his notes on three small cards tucked into his pocket, but he spoke without them, fluently and passionately, assailing the immoralities of the Nixon era from Vietnam to Watergate. To many people in this university town, Hersh was a hero, and they applauded frequently. Hersh more than earned his fee. For Hersh, who had bankrupted himself as he traveled around the world to research The Price of Power, it was one of hundreds of talks to fill the coffers before the great investigative reporter zeroed in on his next target. He has had, in fact, two careers: the journalist who has produced hundreds of newspaper

I did not speak to Sy Hersh again for nearly twenty years as he produced five more books, all controversial, a few documentary films, and dozens of articles for the New Yorker magazine. Thats when the chase began in earnestto try to get Hersh to do what he despisedtalk about himself. In 2004 I had decided to write his biography. He was sixty-seven years old, and I had filled folder after folder with old yellowed newspaper clips and bookmarked more websites with Sy Hersh profiles and commentaries than I thought my computer could hold. I sent him a registered letter to tell him my intentions. He had to walk to the post office in 102-degree Washington DC heat to pick it up. Not a great start. I had no clue if he would cooperate. He had long been intensely private and media shy, except when promoting a book or expos for the New Yorker because then, after all, it was about the work. He had refused again and again to discuss his family or his upbringing. God, this is all so tedious, he told one interviewer who made the mistake to ask about his early life. What the hell does it have to do with anything I write? One of the worlds most famous investigative reporters did not think he was the story. Then again, at times there have been serious threats made against him, when a story touched a nerve, which may explain his reluctance to open his family life.

When his older sister said she would love to talk to me, Sy vetoed the possibility. She knows little about my work, he insisted. I went back and forth with his twin brother, Alan, who also was willing to be interviewed. But weAlan and Icould never agree on terms that assuaged Sy. Hershs wife never answered my letter requesting an interview; Hersh had told me a long time ago I would not be able to interview her. Getting a lens on Sy Hersh through his family became impossible, which left, mostly, his

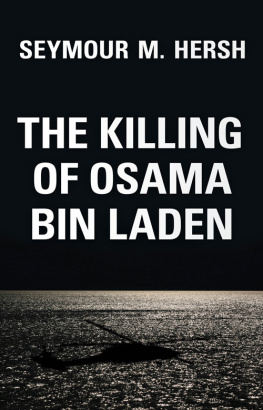

Still, I was hopeful Hersh would talk to me, his first biographer. Look, he said, in his famously rapid style when I first called him in 2004, I am not dead yet. That the world knew. He had re-emerged on center stage that year, reporting on the aftermath of the 9/11 tragedy that had struck America. His expos of the American torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib in Iraq was groundbreaking. Awards poured in; he was profiled in magazines. While many applauded him, one Bush administration official called him the terrorist of American journalism. From the presss point of view, he was back. Of course, he had never really left, as this book shows. From My Lai in 1969 to Abu Ghraib in 2004logical bookendshe was remarkably productive, successful, and controversial. And, along with his longtime rival Bob Woodward, he has surely been Americas most well-known investigative reporter. You cant draw up a pantheon of American reporters that doesnt include Hersh, says author Thomas Powers. If its a pantheon of two, hes one.

Next page